What Is Noh Theatre?

By Something CuratedDerived from the Sino-Japanese word for “skill” or “talent,” Noh is a seminal form of classical Japanese dance-drama that has been performed since the 14th century. Developed by Kan’ami Kiyotsugu, a Japanese Noh actor, author, and musician during the Muromachi period, and his son Zeami, an actor and playwright, Noh is considered to be the oldest major theatre form that is still practiced today. Noh performances are typically based on tales from traditional literature with a supernatural being transformed into human form, serving as the protagonist and narrator. The nuanced art from integrates masks, costumes and various props in a dance-based performance, requiring highly trained actors and musicians. Among the best-known Noh titles are Lady Aoi, The Damask Drum, Dōjō Temple, The Tippling Elf, and The Wind in the Pines.

One of the earliest precursors of Noh is sangaku, which was brought to Japan from China in the 8th century. At the time, the term sangaku referred to various types of performances, featuring acrobats, song and dance as well as comic sketches. Its subsequent adaptation to Japanese society led to its assimilation of other traditional art forms. Various performing art elements in sangaku as well as elements of dengaku, pastoral celebrations performed in connection with rice planting; sarugaku, popular entertainment including acrobatics, juggling, and pantomime; shirabyōshi, traditional dances performed by female dancers in the Imperial Court in the 12th century; gagaku, music and dance performed in the Imperial Court beginning in the 7th century; and kagura, ancient Shinto dances in folk tales, evolved into Noh.

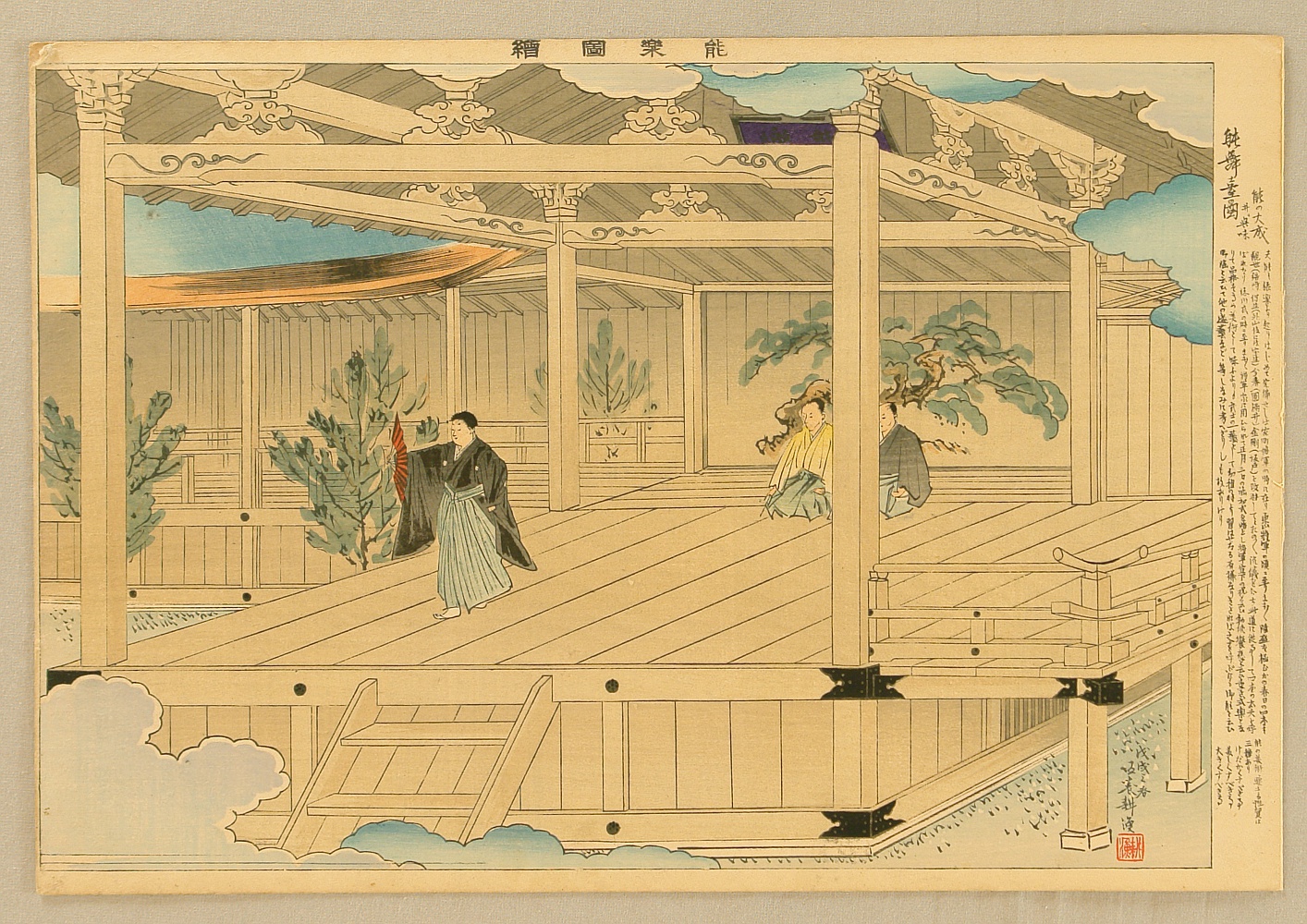

Traditionally, the Noh stage is entirely open, offering a collective experience for both the players and the audience throughout the performance. Eschewing any proscenium or curtains to impede the view, the audience sees each actor even during the moments before they enter and after they exit the main stage. The theatre itself is considered symbolic and treated with reverence both by the performers and the audience. One of the most recognisable features of the Noh stage is its independent roof, which hangs over the stage even in indoor theatres. Supported by four columns, the roof denotes the sanctity of the stage, with its architectural design borrowed from the sacred pavilions of Shinto shrines. The roof also unifies the theatre space and demarcates the stage as an architectural entity.

On stage, Noh actors don silk costumes called shozoku along with wigs, hats, and props such as the fan. Featuring striking colours, elaborate textures, and intricate embroidery, shozoku are impressive works of art in their own right. The use of props in Noh is minimalistic and stylised. The most commonly used prop in Noh is the fan, as it is carried by all performers regardless of role. Chorus singers and musicians may carry their fan in hand when entering the stage, or carry it tucked into their obi. The fan is usually placed at the performer’s side when they take position, and is often not taken up again until leaving the stage. During dance sequences, the fan is normally used to represent any and all hand-held props, such as a sword, wine jug, flute, or writing brush; the fan may represent various objects over the course of a single play.

Actors convey emotions primarily with gestures while the striking Noh masks represent their roles. Carved from blocks of Japanese cypress and painted with natural pigments on a neutral base of glue and crushed seashells, there are approximately 450 different masks mostly based on 60 archetypes, all of which have distinctive names. Noh masks signify the characters’ gender, age, and social ranking, and by wearing masks the actors may portray youngsters, alternative genders, animals, or other nonhuman characters. Even though the mask covers an actor’s face, the use of the mask in Noh is not a rejection of facial expressions altogether but rather, its purpose is to stylise and codify facial expressions, rousing the imagination of the audience.

Today, Noh masks are prized by Noh families and cultural institutions alike, and Japan’s venerable Noh schools hold the oldest and most valuable Noh masks in their private collections, rarely seen by the public. The most ancient mask is said to be kept as a hidden treasure by the oldest school, the Konparu. According to the current head of the school, the mask was carved by the legendary regent Prince Shōtoku over a thousand years ago. While the historical accuracy of the legend of Prince Shōtoku’s mask may be contested, the tale itself is ancient as it is first recorded in Zeami’s Fūshikaden, written in the 14th century. Some of the masks of the Konparu school now belong to the Tokyo National Museum, and are exhibited there regularly.

Feature image: © Toshiro Morita