Tanzanian Artist & Writer Valerie Asiimwe Amani On Plans For Her South London Gallery Residency

By Something CuratedTanzanian artist and writer Valerie Asiimwe Amani is the inaugural Roberts Institute of Art (RIA) and South London Gallery (SLG) Performance Artist in Residence. Amani, who studied at the Ruskin School of Art, works across performative video, text, textiles and installation. The artist’s five-week residency will culminate in a live performance at the SLG from 10-12 June 2022. The performance work is planned to be an intimate look into how the home structure speaks to our understanding of navigating communal space and a sense of belonging, reflecting on the hybridity of traditions and ways in which we remember, share history and play. To learn more about Amani’s intriguing practice, what she has planned during her SLG residency, and what we can expect from her upcoming performance this summer, Something Curated spoke with the artist.

Something Curated: Can you give us some insight into your background and journey to writing and art-making?

Valerie Asiimwe Amani: Well I come from a (mostly) conservative Tanzanian family – my parents both valued education and would constantly encourage my siblings and I to read; art was not a big feature but culture in the form of travelling around Southern and East Africa was. I started writing in a diary since grade 3 – so writing has almost been a consistent way for me to gather my thoughts; art-making however was not as straight forward seeing as I didn’t step foot into a gallery until the age of 26. Art didn’t seem accessible to me especially because I had no frame of reference – however I did have FashionTV (and my mother’s wardrobe) and started cutting up my clothes and painting my shoes and so after completing a Bachelors in Economics I bargained with my parents, convincing them to let me study Fashion Design. After a few years of working as a stylist and designer I realised my concepts for garment making were extending far beyond clothes and runways.

My final runway show ended in a sort of performance piece in support of visual artists who were being affected by the new fees imposed by the Tanzanian government at the time. I started playing around with free video editing software along with Photoshop, and transformed my diary entries into poetry and prose. I became obsessed with creating collages and small videos that included all these elements, but mostly I was just doing it because it brought me peace. It took me working at an art centre in Dar es Salaam (Nafasi Art Space) to realise I was making art. I remember one of the artists there pointing out, “You know you are an artist right?” and although I was flattered I just didn’t believe him. So for the first 3 years of creating art I just referred to what I did as “artistic explorations.” A lot of what I do is still exploring, although now I have the opportunity to share this journey with people and I am proud of being a frame of reference to my nieces and nephews.

SC: Your practice embraces performance, video, text, textiles and installation — how would you describe the approach or conceptual thread that tethers these diverse outputs?

VAA: I often start a piece as either a personal reflection; a reaction; or a group of observations, usually in the form of writing. As an approach I like making narratives around what I create – I am really interested in myths, folklore and the metaphysical and this finds a way of translating into a lot of symbols, motifs and rituals being used in my work along with a back story for the pieces. The best way to explain it is that I feel as if each idea tells me how it wants to exist, some works need dialogue or sound and some need stillness and quiet. I imagine the works themselves as different spirits that want to inhabit different mediums. Looking at what I have created I am now starting to see links such as recurring body parts like hands, legs and impressions of a body. Honestly this is a hard question for me to answer and one I may never have a concise answer to, but I think I like it that way.

SC: What are you planning to work on during your residency at the South London Gallery (SLG)?

VAA: The residency in partnership with the Roberts Institute of Art is a performance focused residency and so I will be working on creating a new performance piece that will end in public events and interventions. I am mostly excited about the chance to have a public performance since this hasn’t been possible recently due to the pandemic and a much welcomed exploration is moving my performative video work into a physical space with live participants.

SC: Could you expand on your interests in communal space and a sense of belonging — how do you broach these ideas in your work?

VAA: Well I found creativity, safety and understanding through a communal art space and realise how communing and community play such a big role in being seen/heard and this in turn aids in perceiving oneself and finding joy. I grew up in Dar es Salaam, Harare, Kigali and Johannesburg – these are very different cities in quite different countries and from a young age had to learn the importance of approaching a new space and people with care and respectful curiosity. I learned that home is not a place but of course the people in the place and how they can (or cannot) navigate and live in it. Without space or a place of familiarity it is hard to settle and I guess I relate settling to feeling like you are safe, like you don’t have to worry or worry alone.

I think this shows itself in my work through the often subtle and sometimes overt reference to a “we,” an “us” or a “you and I.” In many ways, “othered” communities are still fighting to belong, to be counted as well as mediating histories of trauma and exclusion. As an offering to this, my work explores ideas of healing, of creating alternative histories and inclusive stories and exploring what it may mean to create personal joy that extends into a communal joy.

SC: Are you able to tell us anything about the live performance you have planned at SLG in June?

VAA: I do not want to say too much prematurely, however it will be informed in part by the physical community in South London, considering the rich history and diverse locality of language, food and culture; as well as interactions with my online community. Rooted in the idea of home as a place of tension and a place of becoming, or breaking or mending. As I work across various mediums, it will also be a way to have a culmination of different elements including, sound and video – but how all this will come together will be worked out in the coming weeks.

SC: And what are you currently reading?

VAA: After quickly consuming Akwaeke Emezis’ Death of Vivek Oji, which was deeply emotional and a thing of beauty, I have been engrossed in Azadi by Arundhati Roy which is a collection of essays on freedom. I’m taking my time because of the richness of all she writes about in concepts of freedom, language and land, specifically focusing on the complex cultural past and present of The Republic of India. Which, coincidentally, has been further informing my research on how complex language is and the consequential failure of translation as a means of communicating and mediating identity.

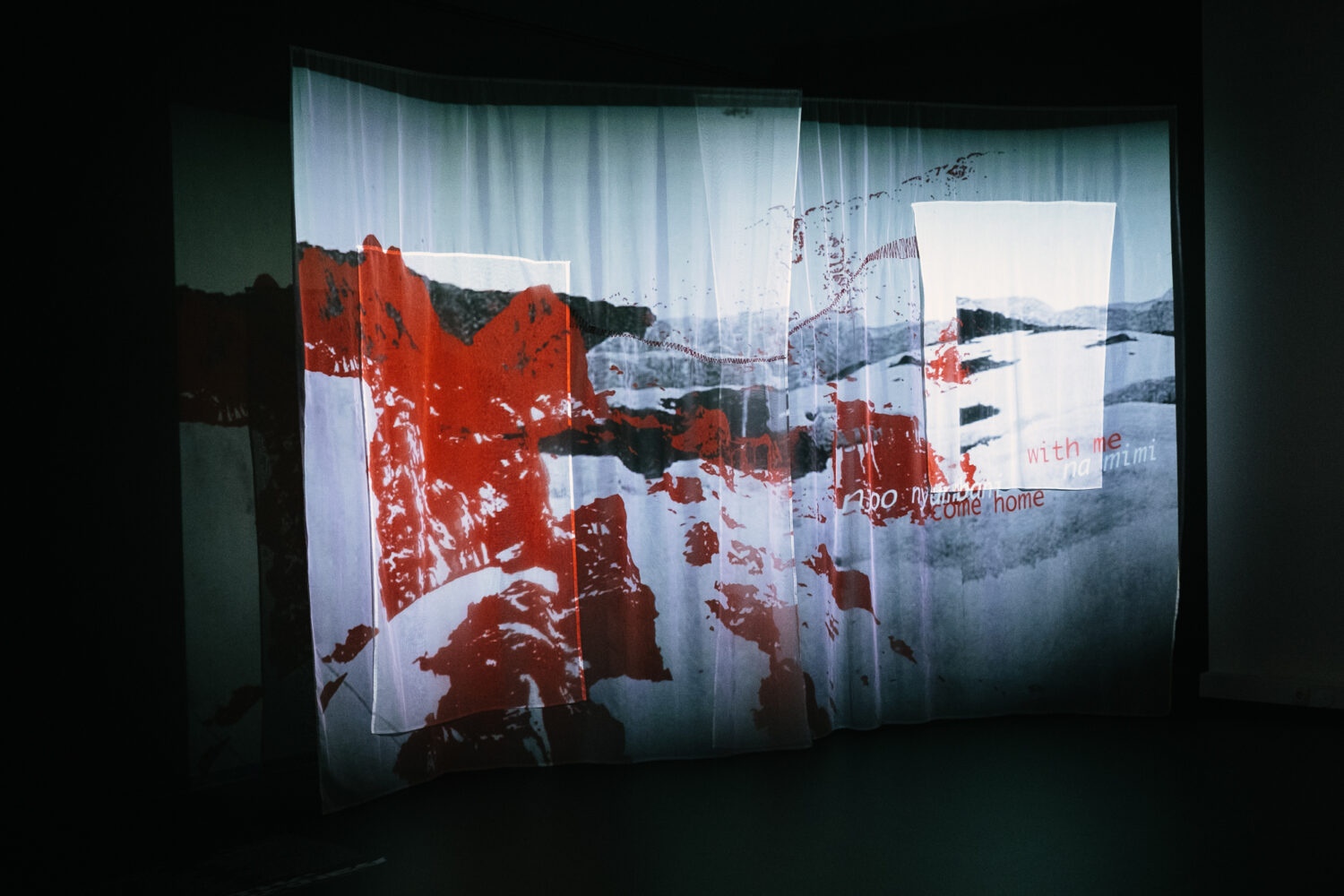

Feature image: Valerie Asiimwe Amani, A Confluence Of Parts (video still), 2021. Courtesy the artist