The Politics Of Paper-Cutting

By Something CuratedThe oldest surviving paper-cut work is a symmetrical circle from the 6th century found in Xinjiang, China. Ka-ming Wu, Professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, explains that in the 20th century, paper-cuts have been variously regarded as a domestic craft, a site of rural purity, a marker of Chinese civilisation, and more recently, a national intangible cultural heritage. “Paper-cuts are not merely a cultural practice but a medium of articulation through which Chinese urban intellectuals have understood the countryside and traditions at specific historical moments,” she notes. “Paper-cuts have acted as a cultural medium through which urban elites have expressed their visions of the nation’s path to modernity and women’s liberation. During the Yan’an period (1937–1947), paper-cuts served as a Communist marker to distinguish an “art form of healthiness and honesty” from urban decadence under Nationalist rule. Since the 1980s, however, the art and practices of paper-cutting have come to share new discursive spaces: as the site of recovery of a lost Chinese civilization, an urban nostalgia for vanishing rural ritual practices, and most recently, a discourse of capital, profit, and personal success,” she continues.

Elsewhere in Asia, the Japanese art of paper-cutting known as kirie or kirigami, translating in English to “cut picture,” is widely thought to have been developed after 610 AD when Tesuki washi paper, invented in China, was brought to Japan by Doncho, a Buddhist monk from Korea. The Japanese commercialised paper-making by hand and by 800 AD their skills were unrivalled. The abundance of Japanese washi meant paper-cutting and offshoots such as kamikiri, performance paper-cutting in Edo Japan, evolved at a very rapid pace. The washi paper used most predominantly across the world today for paper-cutting, book binding, tapes and multiple other uses is not Tesuki washi but actually Japanese Sekishu washi, a paper produced around 800 AD in the Sekishu region. Paper-cutting continues to be a prevalent practice in Japan in contemporary forms, manifesting commonly as framed artworks given as gifts, ritualistic installations and decorative paper sculptures.

Design scholar Natalie Avella writes, “Paper was at first a precious commodity, and as a result, paper-cutting did not spread widely until after 600 CE. Once the secret of making paper spread to the Middle East (leaked, some scholars say, during military invasions of China when artisans bartered such secrets for mercy), the Muslims quickly built paper mills and developed machinery for bulk manufacturing. Baghdad became the world’s first paper-making centre, and mills were built there beginning about 794 CE. In Turkey, paper-cutting was recognised as an industry early on. Eleventh-century artisans were cutting pictures for the popular shadow theatres, and by the sixteenth century, there was a guild of paper-carvers. In 1582, the paper-cutters are documented to have filed past the sultan exhibiting a beautiful garden and a castle decorated with flowers made of multi-coloured papers. Paper was such a powerful commodity that the Christian church tried to boycott it as for many centuries, because it feared that the Muslim world was trying to dominate trade and culture through paper.”

Famously, during the last decade of his life Henri Matisse deployed two simple materials, white paper and gouache, to create works of wide-ranging colour and complexity. An unorthodox implement, a pair of scissors, was the tool Matisse used to transform paint and paper into a world of plants, animals, figures, and shapes. Long before the cut-outs spread across Matisse’s walls to become immersive, environmental works, Matisse dreamed of creating on a grand scale. In 1942, he expressed to the writer Louis Aragon that he had “an unconscious belief in a future life… some paradise where I shall paint frescoes.” And in 1947, he acknowledged the influence of Islamic art which, he said, “suggests a greater space, a truly plastic space.” Building upon the cut-out medium allowed him to fulfil this ambition to make monumental decorations that transcended the confines of easel painting.

In Mexico, San Salvador Huixcolotla in Puebla State is considered to be the birthplace of papel picado, meaning “perforated paper” in English. During the Spanish colonisation Puebla State was on the trade route that traversed the Philippines to Acapulco at the Pacific Ocean, and then continued via land from Veracruz on the Gulf of Mexico to Spain. Among the traded items that remained in the region was a thin and coloured paper made of silk that was given the name papel de China, or China paper. It is not known exactly how people from San Salvador began cutting paper flags but by the late 1920’s the town crafters were travelling to neighbouring towns and later to Mexico City to sell their paper flags. The tissue paper is cut in the desired shape and size and stacked over a lead plate used as a base, before being carved using chisels. By the 1970’s it had become a tradition around central Mexico to decorate Day of the Dead altars, buildings and streets with papel picado flags, now a ubiquitous tradition across the country.

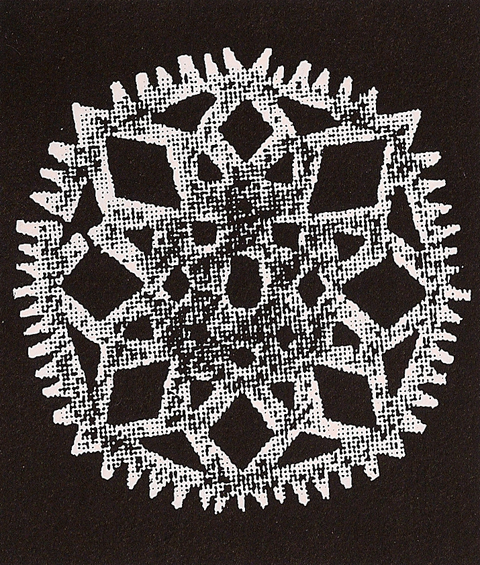

Today, perhaps one of the most radical and politically charged uses of paper-cuts in contemporary art comes from Kara Walker, who is among the most complex and prolific American artists of her generation. She has gained national and international recognition for her cut-paper silhouettes depicting historical narratives haunted by sexuality, violence, and subjugation. Walker has also used drawing, painting, text, shadow puppetry, film, and sculpture to expose the ongoing psychological injury caused by the tragic legacy of slavery. Her work leads viewers to a critical understanding of the past while also proposing an examination of contemporary racial and gender stereotypes. The silhouette technique Walker borrows from has its roots in the sentimental Victorian “ladies’ art” of shadow portraits, but the scale of Walker’s work also alludes to the 360-degree historical cycloramas popular during the post-Civil War era for the depiction of battle scenes.

Currently on view, in her solo presentation, Mesmerizing Mesh – Paper Leap and Sonic Guard at Barbara Wien, Berlin, and running until 30 July 2022, South Korean artist Haegue Yang shows a series of hanji, traditional Korean paper, collages. Hanji is made from the inner bark of the mulberry trees native to Korean mountainsides. The distinctive use of paper in regional shamanistic traditions in Korea inspired the artist. Across civilisations, individuals and collectives have used paper in various rituals to convey their wishes. These paper props are also used for purification or cleansing rites and often burned at the end. Among the myriad of compositions displayed in Yang’s show are an array of geometric and abstract patterns referencing sumun, an ornamented paper sheet, which is hung from the ceiling in ritual sites to protect against evil spirits.

Bibliography:

Ka-ming Wu, Modern China Vol. 41, No. 1, 2015. Published by Sage Publications, Inc.

Laura Heyenga and Natalie Avella, Paper Cutting: Contemporary Artists, Timeless Craft, 2011. Published by Chronicle Books LLC

Henri Matisse. The Cut-Outs, MoMA

Dyana Agur, Mexican Folk Art Guide, Papel Picado, 2009

Thomas A. Green, Folklore: An Encyclopaedia of Beliefs, Customs, Tales, Music, and Art, 1997. Published by ABC-CLIO

Kara Walker. Education, Cut-Paper Silhouettes, Endless Conundrum, an African American Anonymous Adventuress, Walker Art Center

Barbara Wien gallery & art bookshop, Haegue Yang Mesmerizing Mesh – Paper Leap and Sonic Guard, April 29 – July 30, 2022

Feature image: Kara Walker, African/American, 1998. © Kara Walker. Photo: MoMA