A History Of The Persian Rug

By Something CuratedWith a history spanning more than 2,500 years, the art of carpet weaving in Iran was initially born out of necessity. Pragmatic coverings, these textiles were created to insulate the temporary homes of nomadic tribes people, placed on the ground to provide protection from cold temperatures and moisture. Over the centuries, the skill of carpet making grew to be a valuable and celebrated craft, one that has been proudly passed down by generations and has become increasingly elaborate. The motifs in the carpets are trademarks of the makers; tribal weavers believed that the symbols protect the rug’s owner from misfortune. Archetypical designs include everything from representations of historical monuments and Islamic buildings, to nature, with popular references including the Tree of Life and the Garden of Paradise. Meticulously hand knotted, whether made with wool or silk, a single rug can take months or even years to complete. With the arrival of international trade, the craft further diversified, with artisans innovating new patterns and designs to satiate a swiftly growing market.

The evolution of the Persian carpet can largely be traced in parallel with Iran’s rulers. When Cyrus the Great conquered Babylon in 539 BC, it is said that he was enamoured by the city’s exceptional craftsmanship — and some historians even credit him for bringing the art of carpet making into Persia. The tomb of Cyrus, who was buried at Pasargadae near Persepolis, was covered with ornate and precious carpets. In saying this, even before his time, findings suggest Persian nomads created practical rugs for their own homes. They kept sheep and goats, which provided high quality and durable wool for carpet making, among other uses. In 1949, Russian archaeologists uncovered the oldest known knotted carpet in the Pazyryk valley, on the Altai Mountains of Siberia. Dating back to the 5th century BC, the Pazyryk carpet is a fine example of the skill which existed and has been developed and refined over the centuries. The carpet withstood over two millennia, preserved in the frozen tombs of Scythian nobles, and is now a prized part of the Hermitage Museum’s collection.

In 628 AD, Eastern Roman Emperor Heraclius brought back a variety of carpets from the conquest of Ctesiphon, the Sassanian capital and centre of the Neo-Persian Empire. Shortly after, the Arabs also conquered Ctesiphon, and among the plunders brought back were copious carpets, one of which was the famous garden carpet, known as the Spring of Khosrow. This legendary rug was enormous, measuring 400×100 feet and weighing several tonnes. A historical account describing the rug elaborates: “The border was a magnificent flower bed of blue, red, white, yellow and green stones; in the background the colour of the earth was imitated with gold; clear stones like crystals gave the illusion of water; the plants were in silk and the fruits were formed by coloured stones.” King Khosrow I is said to have meandered along the carpet in winter to remind him of the beauty of spring. Unfortunately, when the Arabs seized the carpet, they cut the glorious piece into several parts to sell.

Following the period of domination by the Arab Caliphates, a Turkish tribe, named after their founder, the Seljuk, conquered Persia. The Seljuk women were adept carpet makers known for employing Turkish knots. In the provinces of Azerbaijan and Hamadan where Seljuk influence was strongest and longest lasting, the knot is used to this day. The Persian carpet reached its peak during the reign of the Safavid Dynasty in the 16th century AD. Approximately 1500 examples are preserved in various museums and in private collections worldwide. During the reign of Shah Abbas (1587-1629), commerce and crafts prospered in Persia. Shah Abbas encouraged contacts and trade with Europe and transformed his new capital, Isfahan, into one of the most magnificent cities in Persia. He built workshops for carpets where skilled designers and craftsmen set to work to create exceptional pieces. Most of these carpets were made of silk, with gold and silver threads adding glistening adornment.

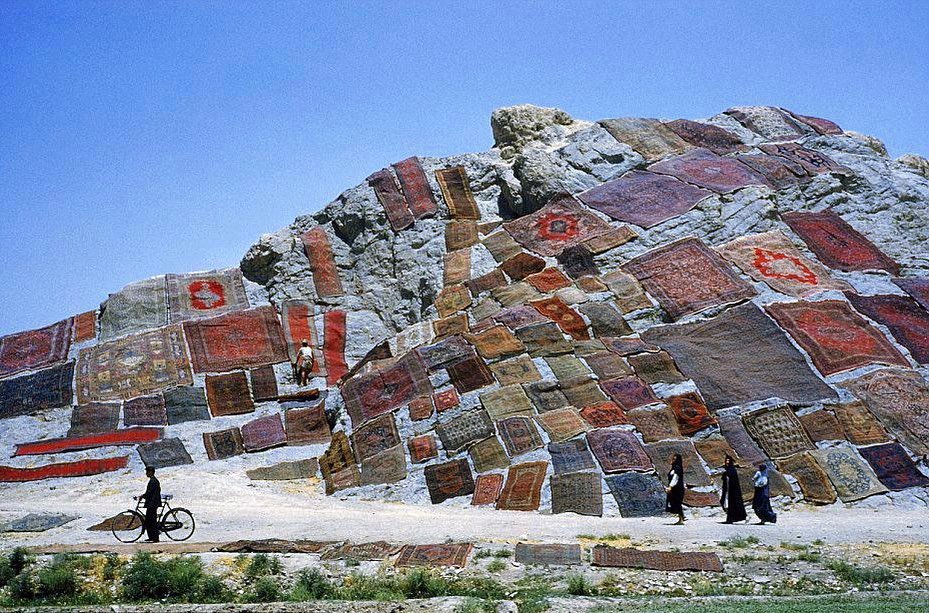

This flourishing period concluded with the Afghan invasion in 1722. Though the Afghans overthrew Isfahan, their power lasted for only a short time and in 1736 a young Chieftain from Khorasan, Nader Khan, became the Shah of Persia. During this time, and for several tumultuous years after his passing in 1747, no carpets of notable value seem to have been made. It was in the last quarter of the 19th century, and during the reign of Qajar, that trade and craftsmanship regained their importance. Carpet making boomed once more with Tabriz merchants exporting extensively to Europe via Istanbul. By the end of the 19th century a number of European and American companies even established businesses in Persia, organising craft production destined for Western markets. Today, prized possessions in palaces, private collections and museums across the world, Persian carpets remain widely coveted for their meticulous artistry, splendorous colours and enduring quality.

Feature image: Persian Tabriz Pictorial Rug, North West Persia, Kork Wool with Silk Highlights on Silk Foundation, Mid 20th Century. Photo: Essie Carpets