Remembering Issey Miyake (1938-2022)

By Something CuratedA germinal figure in the history of fashion, Issey Miyake’s generous and influential contribution to the industry is impossible to overlook. The designer, who sadly passed away from liver cancer at the end of last week, was instrumental in shaping fashion today, championing an approach that celebrates the beauty of the unconventional. Miyake relentlessly expanded definitions of garment making, eschewing familiar proportions and symmetry, allowing wrapped textiles to respond to the body’s shape at their own will, and rejecting notions of trend. His concepts were indisputably original, subverting an establishment previously defined by Western designers. Miyake was born during the spring in 1938, in Hiroshima, Japan, where he witnessed the atomic bombing of 1945. As a young child, he had aspirations of becoming a dancer but his interest in fashion overtook these early ambitions thanks to the discovery of his sister’s collection of magazines.

Miyake went onto study graphic design at the Tama Art University in Tokyo, graduating in 1964. He then enrolled at L’Ecole de la Chambre Syndicale de la Couture Parisienne in Paris, apprenticing for French fashion designers Guy Laroche and Hubert de Givenchy. In 1969, Miyake made the decision to relocate to New York, taking English classes at Columbia University and working for designer Geoffrey Beene. It was during this time that he formed friendships with artists like Christo and Robert Rauschenberg. From a young age, Miyake was compelled by art, and had a great respect for Isamu Noguchi in particular, whose innovative approach to material is said to have influenced Miyake’s work. Returning to Tokyo in 1970, the young designer founded the Miyake Design Studio, initially a womenswear label. The following year saw the presentation of his first collection in New York, and shortly after, in 1973, Miyake returned to Paris.

It was in Paris that Miyake established the foundations for avant-garde designers on an international scale, pushing doors down for his Japanese peers in particular. His presentations, which took place in swimming pools and featured eighty-year-old models and light shows became anticipated spectacles on the fashion calendar. Miyake was showing in Paris long before other Japanese designers, and his presence was further pronounced by the emergence of two influential and progressive designers. Rei Kawakubo, working under the label Comme des Garçons, and Yohji Yamamoto began to present their collections in Paris in 1981 along with the already-established Miyake, who was regarded as the founding father of the new fashion wave. These three effectively started a new school of Japanese avant-garde fashion, although it was never their intention to categorise themselves as such.

In the late 1980s, Miyake had begun to experiment with new methods of pleating that would allow both flexibility of movement for the wearer as well as ease of care and production. The garments were cut and sewn first, then sandwiched between layers of paper and fed into a heat press, where they are pleated. The fabric’s memory holds the pleats and when the garments are liberated from their paper cocoon, they are ready to wear. Building on a seminal collection of costumes he created for the Ballett Frankfurt, with the support of his textile director Makiko Minagawa and the Japanese textile mills, Miyake introduced his most commercially successful collection, Pleats Please, to the world in 1993.

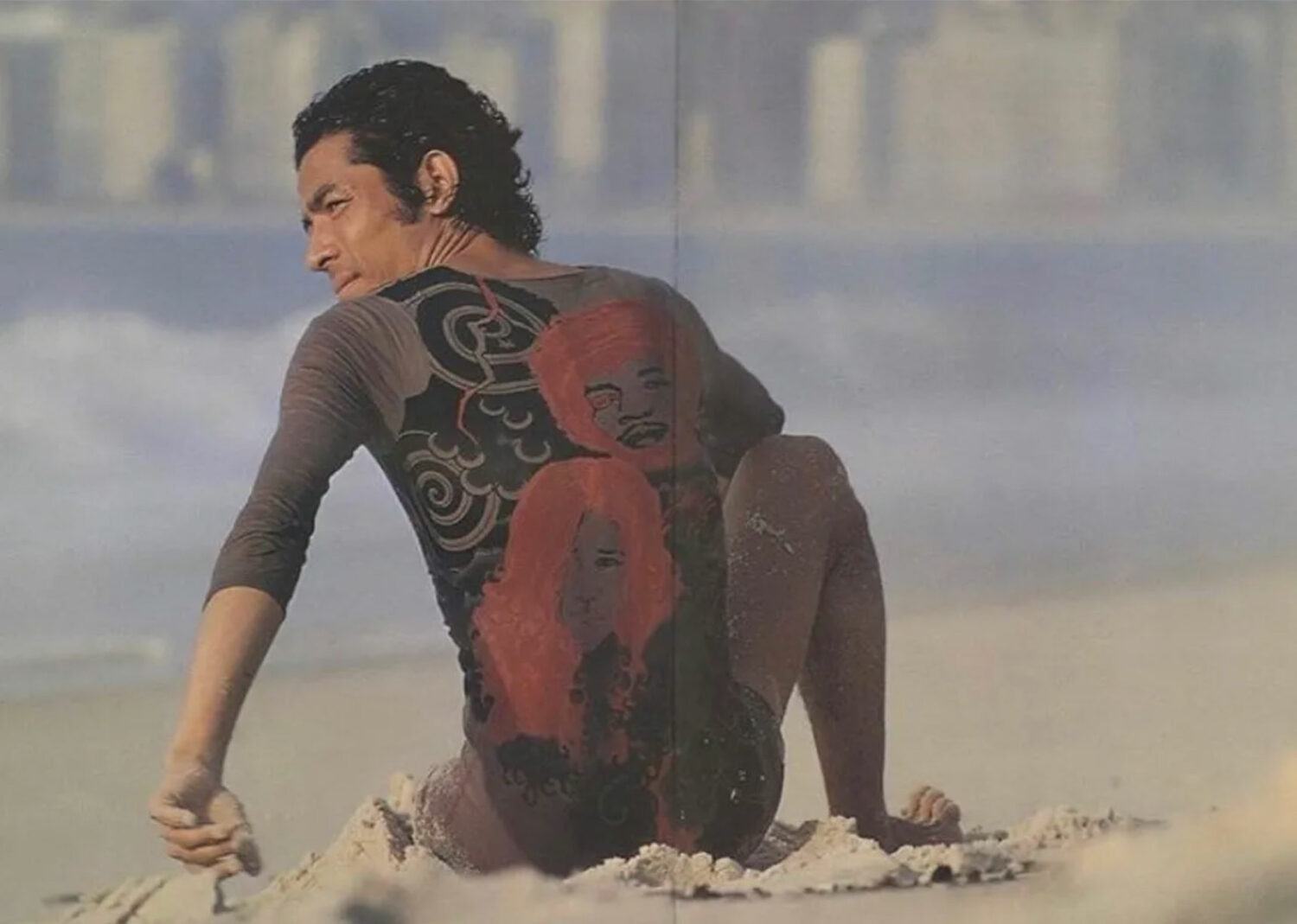

At the end of the 90s, he brought one of his most conceptual lines, A Piece of Cloth (A-POC), to the market, which evolved from works he had made as early as 1976. The A-POC garments consist of a long tube of jersey from which individuals can cut without wasting any material. A large variety of clothes can be made in this manner. The tubes themselves are manufactured with a knitting machine controlled by a computer and can be made easily in large quantities. Miyake’s objective with these pieces was to minimise waste by using only leftover and discarded materials. These clever garments allow the buyer to size and cut out various wearable items, from a hat and gloves to socks, a skirt, or a dress, depending on the way in which the tube is divided.

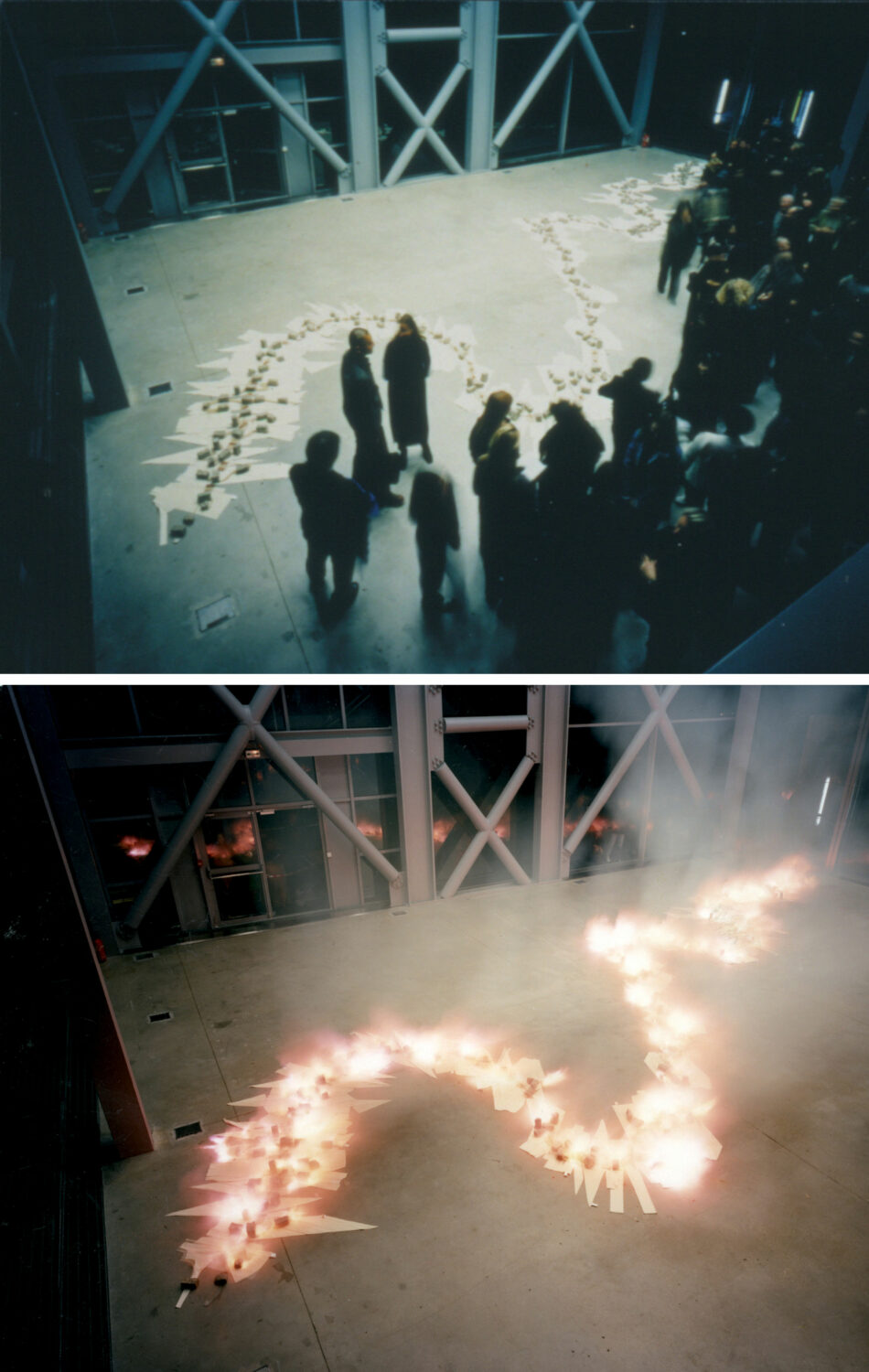

Cementing his place as a household name in fashion, Miyake earned commercial and critical success with his clothing lines going onto introduce a fêted perfume collection, with L’eau d’Issey becoming an instant classic. Interestingly, he was also behind Apple co-founder Steve Jobs’ famed black turtlenecks, which Jobs became synonymous with. Through the latter half of the 90s, Miyake collaborated with various artists for his Guest Artist series; one of the most memorable collaborations from this project was with Chinese artist Cai Guo-Qiang who used gunpowder to print on Miyake’s creations. Miyake proclaimed that his intention was not to answer the question, “Is fashion art?” but rather to facilitate an “interactive relationship” between the art and the people who admired it. For Miyake, by wearing the artworks upon their bodies, the wearers engaged with both fashion and art at once.

By the end of 1999, Miyake turned over the design of both his men’s and women’s collections to his associate, Naoki Takizawa, so that he could return to research full-time. Today, the label’s design responsibilities are shared between Yoshiyuki Miyamae and Yusuke Takahashi. In 2012, Miyake was named as one of the Co-Directors of 21_21 DESIGN SIGHT, Japan’s first design museum, and 2016 saw the largest retrospective of his work organised at The National Art Center in Tokyo, celebrating 45 years of the designer’s illustrious career. Miyake is a true pioneer with an influence spanning generations; he redefined sartorial standards, critically reimagining conventional norms for the production of garments. He allowed the wearer to decide how to utilise their garments themselves, pushing the consumer and industry to be creative and think beyond tradition.

Feature image: A-POC by Issey Miyake and Dai Fujiwara, from the Issey Miyake Spring/Summer 1999 collection. Photo: Yasuaki Yoshinaga