A History Of Khadi, India’s Fabric Of Resistance

By Something CuratedA forerunner of textile making until the 19th century, weaving practices flourished in India since the Bronze Age, with cotton cultivation and processing emerging during the time of the Indus Valley Civilisation. In medieval times, cotton textiles were imported to Rome through the maritime Silk Road and Arabian-Surat merchants traded fabrics with Basra and Baghdad from Gujarat, the Coromandel Coast and the East Coast of India. After the First Indian War of Independence in 1857, domestic textile production by mill or traditional methods declined to its lowest levels before khadi emerged as an unassuming economic revolution. While hand spun and woven cotton cloth of this kind was prevalent throughout India, it was not until the early 20th century, when its production and use were in critical decline, that khadi became a potent visual symbol of India’s resistance of colonial power.

Till today, khadi is the term ubiquitously used throughout India, Pakistan and Bangladesh to refer to varieties of coarse cotton cloth hand woven using hand spun yarn. Historically, this was the cloth typically worn by labouring and artisan groups in pre-industrial India. Made from locally grown cotton, harvested by farmers and spun by local women, the final cloth was woven by men, normally members of specialist weaving families who would have honed their craft for generations. The particular equipment involved in the production of khadi would vary from region to region, as would the techniques used for its adornment, from dying and embroidery to printing. The significance and efficacy of khadi as a tangible emblem of the Indian fight for freedom cannot be explored without recognising the seminal role played by Mahatma Gandhi in uplifting it to the status of a national cloth instilled with almost sacred properties.

The American Civil War of 1865 caused a raw cotton crisis in Britain’s Cottonopolis, a 19th-century nickname for Manchester, then the centre of the cotton industry. Indian cotton at highly discounted prices was sourced for British mills as the textile industry was dwindling in India, and hand spinning was a dying art. During Victorian rule, it is recorded that some fifty Indian mills existed in the 1870s but Indians still bought clothes at an artificially inflated price, since the British colonial government exported the raw materials for cloth to British fabric mills, then re-imported the finished cloth to India for sale. In direct response to this, among a laundry list of atrocities, the Swadeshi movement was born, a self-sufficiency effort that was part of the Indian independence movement and contributed to the development of Indian nationalism.

Famously, in 1919, Gandhi started spinning at Mani Bhawan Mumbai and encouraging others to do so. He pioneered the use of a double spinning wheel designed to increase speed and control. In 1922, he requested the Indian National Congress (INC) to start a khadi department, and within two years, due to a large response to the initiative, a semi-independent body, the All India Khadi Board (AIKB), was formed which liaised with the INC’s khadi department at the provincial and district levels. Shortly after, the All India Spinner Association (AISA) was formed comprising the khadi department and AIKB. The Swadeshi movement vastly increased in size and reach following the patronage of wealthy Indians who donated funds and land to khadi dedicated organisations, which eventually started cloth production in every household.

As the founder of AISA, Gandhi made it essential for all Association members to spin cotton themselves and pay their dues in yarn. Gandhi collected large sums of money to create further grassroots-level khadi institutions to encourage spinning and weaving, creating independent opportunities for communities and eschewing colonially imposed systems of production and consumption. Since India’s independence from the United Kingdom on 15 August 1947, the story of khadi has continued, existing in a balancing act between tradition and modernity. A powerful symbol of resistance, khadi stands for both strength and tradition, but the material’s use and treatment continues to undergo changes to stay relevant. Khadi has seen a new wave of popularity in recent years in large part due to the work of Indian fashion designers like Sabyasachi Mukherjee, Ritu Kumar and Rohit Bal, who are all embracing the material within a contemporary context.

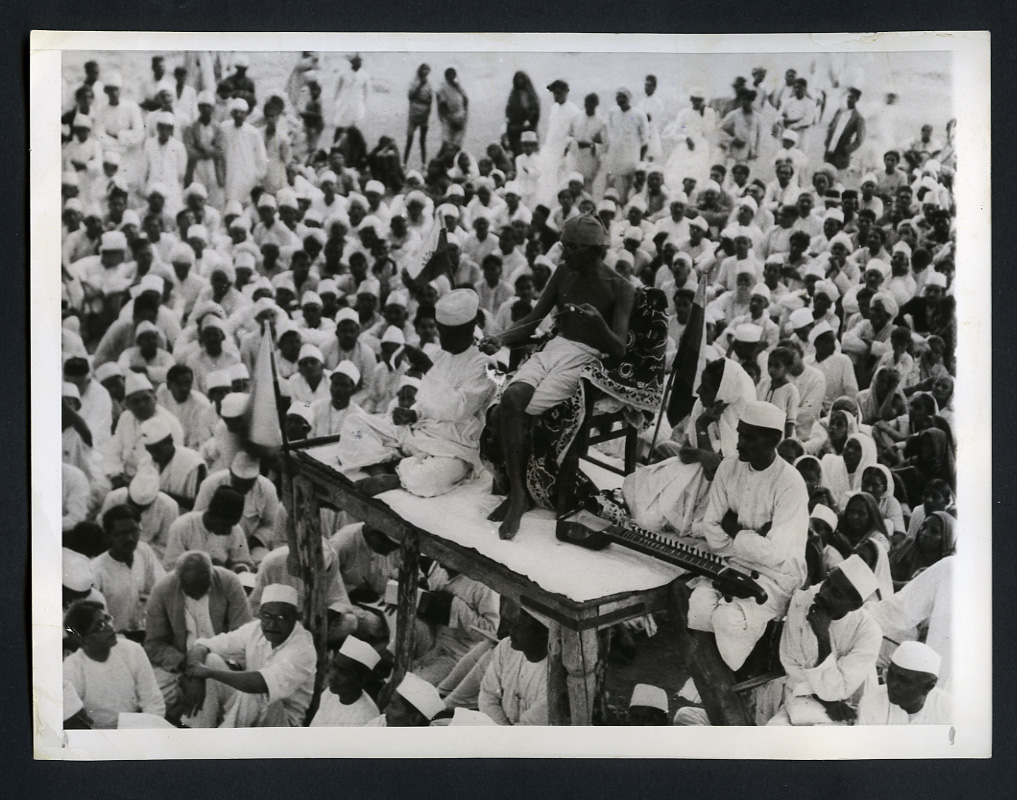

Feature image: Mahatma Gandhi by Margaret Bourke-White. Photo: Pinterest