Interview: Trevor Mathison & Claudette Johnson Talk “Dirty” Sound & The Black Audio Film Collective

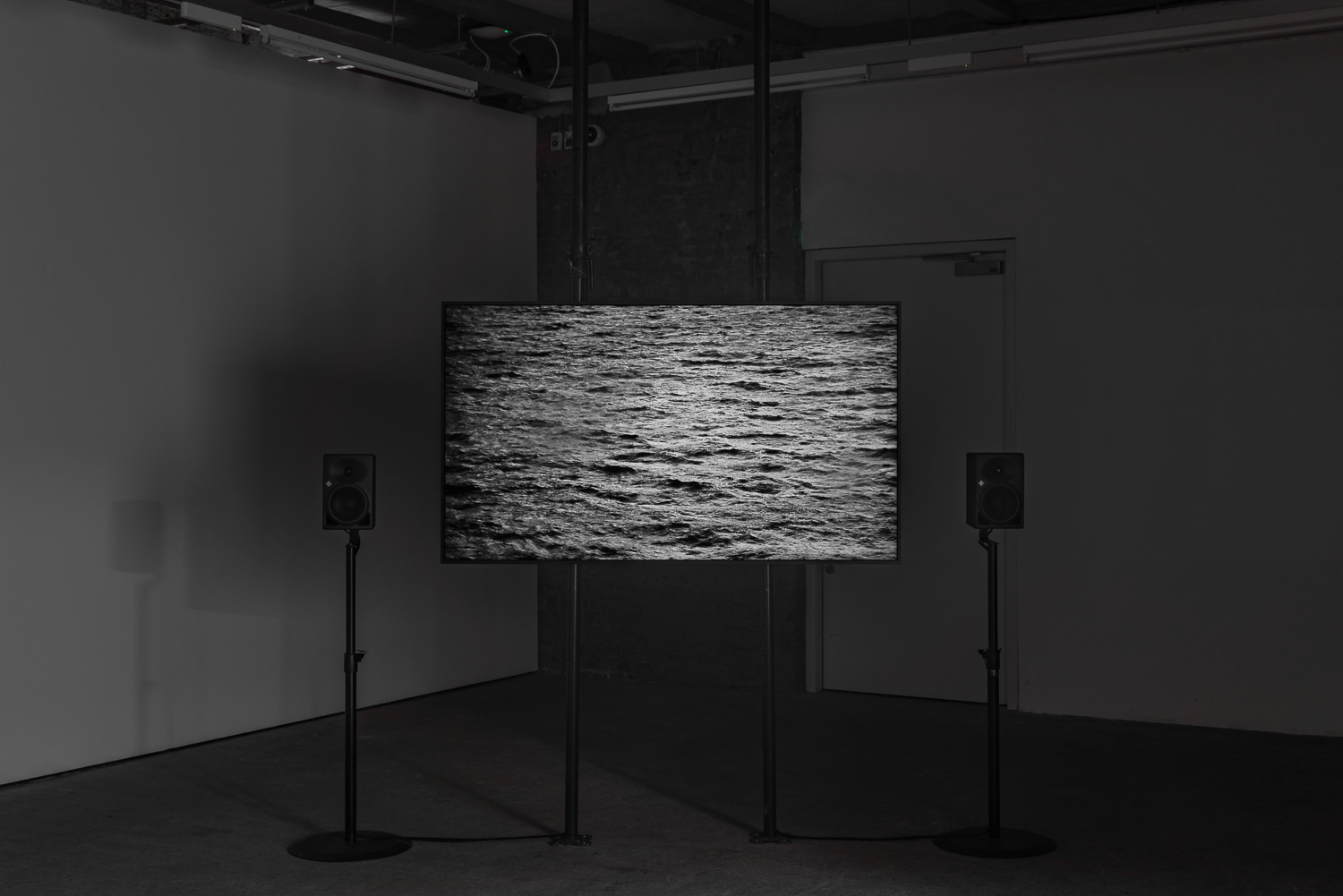

By Something CuratedTrevor Mathison’s sonic practice centres on creating fractured, haunting aural landscapes, often integrating fragments of existing music. Having been featured in over thirty award-winning films, Mathison was a founding member of the cinecultural artist organisation, The Black Audio Film Collective (1982–1998), where his body of sonic designs defined and situated the group’s film and gallery installations. His new solo show at Goldsmiths CCA, From Signal to Decay: Volume 1, open now and running until 18 September 2022, comprises an ambitious new sound installation, an archival presentation of graphic work, video, and live performance. In the months leading up to this exhibition, Mathison undertook a sonic investigation of the Goldsmiths CCA building, producing numerous recordings using an Ambisonic microphone. Now these samples are periodically played back in the first gallery, reverberating with the architecture and providing a constant signal with which other sound pieces in the adjacent spaces can converse and collide. To learn more about his fascinating practice and the new exhibition, celebrated visual artist Claudette Johnson MBE, alongside Something Curated, spoke with Mathison.

Something Curated: Trevor, your practice seamlessly oscillates between sonic and visual outputs – how and when did you first become interested in this intersection?

Trevor Mathison: One of the first things I was interested in was drawing – sketching things in notebooks. But the sound came a bit later on during my time in Portsmouth, and when I left Portsmouth and came back to London. When I was at Chelsea I had access to some equipment; there was some stuff that I was able to do in the mixed media department that I was also able to work at home with – making recordings on cassettes and multitracking, stuff like that. So that’s when it sort of came together.

Claudette Johnson: So you weren’t already working with sound when you left Portsmouth?

TM: No, not really. I was mainly making sculpture and some drawings.

CJ: And what kind of form did the work take at that point?

TM: Installation pieces, objects. Some of the pieces were around ideas of archaeology, which I was interested in. And photography. They were the main elements I was working with from Portsmouth to Chelsea. Sound became more prominent when I was at Chelsea, more experimenting and trying things out.

CJ: So the transition took place slowly.

TM: Yeah, it was slow. Over the matter of a couple of years.

SC: How have you approached utilising the Goldsmiths CCA building both as a site of display as well as production for your new exhibition, From Signal to Decay: Volume 1?

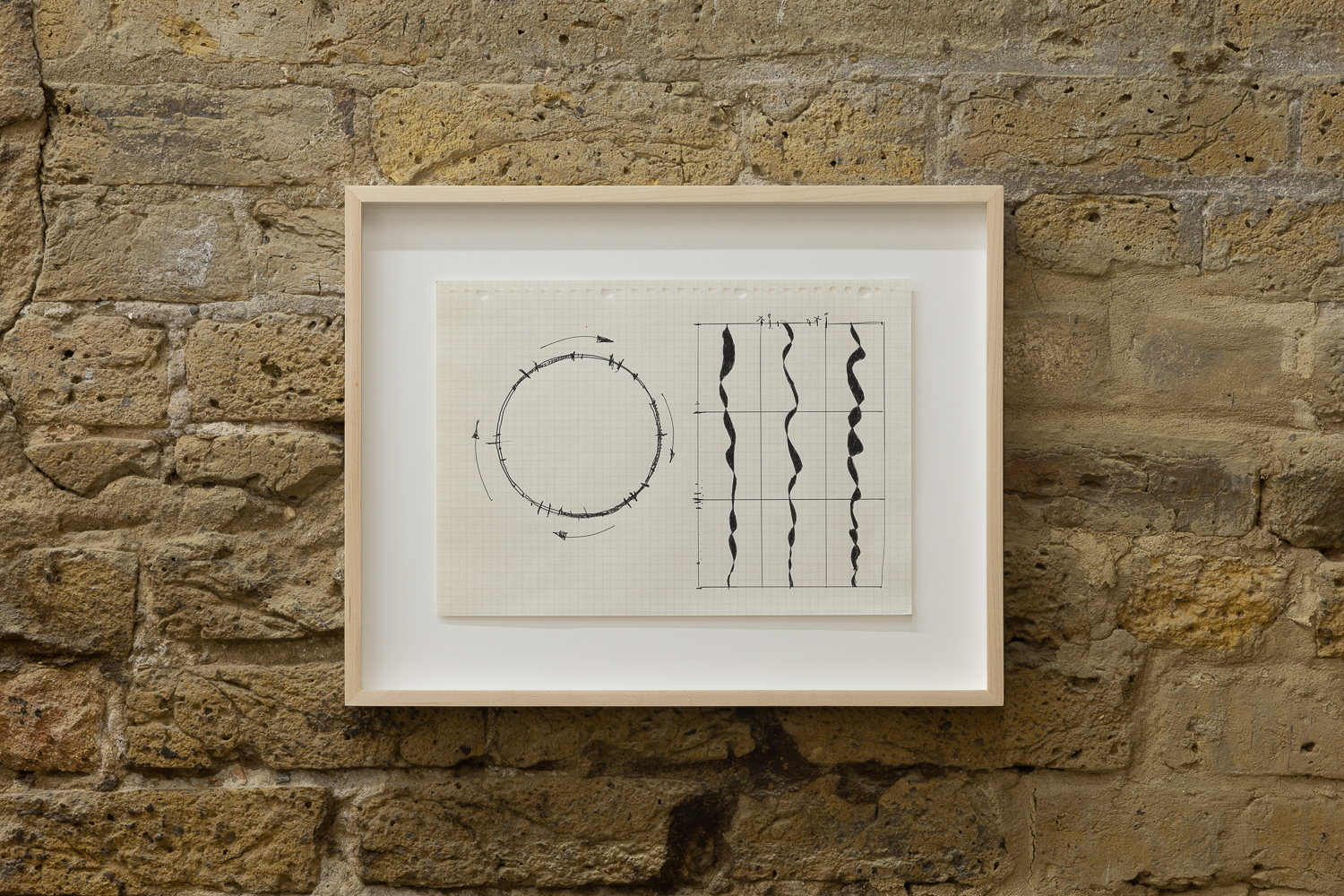

TM: The first bit was just being inside the building and listening to the way that the building reverberated, the sorts of sounds that were going on inside the building and outside, along New Cross Road. So that was my starting point for thinking about what could be done. And then by talking to Oliver [Fuke] and Junior [Boakye-Yiadom] it became more interesting to look at some of the notations, some of the ideas of how I try to visualise some of the sound pieces, or what I thought was going on inside the pieces. And then the space became interesting to see how we could present the sketches, the drawings, and some of the video pieces. And there’s also making the building reverberate as a part of the installation itself.

CJ: Can you say a bit more about the display side of things?

TM: There are interesting departments or spaces inside the CCA building, and each space has a slightly different sort of quality, I think. There’s the corridor, there’s the main space with the high ceiling, there’s the small room. And each of them have a different sort of pathway that I thought was quite interesting. But also the balcony was interesting; people can view the work from the top of the balcony as they walk through. So it was definitely an interesting space to start with, working with its qualities.

CJ: What’s your interest in making spaces reverberate?

TM: One of the things I find interesting is that different environments, or different spaces have different sorts of qualities – the materials that are used, the light, the smell, the texture. A feeling. I’d like that to be a part of the sound landscape. Ambient sound or room tone has a certain quality that you can orchestrate and introduce into sonic scores.

SC: Can you tell us more about the new sound installation you’ve created?

TM: The sound installation is in three parts. Part one is the building itself. A series of recordings that were done inside the CCA – I’ve built those into a sound piece. And then there’s these other built soundtracks that take you on a sonic journey through the space, which locks together the exterior sound of the building itself, the sound pieces that I’ve built, and then also the building with a series of live mic elements. And then there are two video pieces – one represents sound waves, and another represents waves.The latter is a film piece I made in Scotland, which is nature, basically, sort of doing its thing, with another sound score.

CJ: In terms of your work and your process of creating sound pieces, are there recurring elements that you can talk about?

TM: Lots of them have cycles and tones, loops, patterns, and a shift in EQing of that sound. It goes on a mutated sort of journey via effects, and that is built up in layers. There’s a series of layers that are locked in loops, doing their own internal cycle, but working alongside or against another sound which is either stacked on top of it or alongside it, or in the distance. So, I’m playing around with that sort of spatial quality.

CJ: Yeah, because you’ve titled it From Signal to Decay and the signal holds a very wide meaning for you doesn’t it, because of your historic interest in dub and the role that that has played.

TM: Yeah, if not directly, in the background or as a support to actually building, or even a method of thinking through how to make the sound – or to engage with the sound. So yeah, dub plays a big part in all aspects of my approach. Even if it may not sound like dub, there are certain things I take from the experience of listening to it and enjoying the music. There’s a methodology I find interesting to make the sounds that I enjoy now. And those recurring elements keep going back and forth. I like that idea of breaking down tracks by frequency and then creating space for these things to engage again, and reconstructing them within a new sonic environment. Taking out the high frequency, taking out the mid, playing with the bass – reconstructing the experience of listening to music.

CJ: Which is a key part of dub culture, isn’t it?

TM: Yep. And relocating it within the space.

CJ: It’s like a merging of your thinking as a visual artist with your cultural connection to music and to dub.

TM: Well, that’s also the bit about the archaeology of sound. You’re trying to reveal or discover another part, or working out how it’s connected. Is it the shoulder of a dinosaur? Or are these the pots and pans of a past society. Again, it’s making sense of fragments or elements, reimagining the space holding these fragments and elements. That’s also a part of the notion that informs From Signal to Decay – the process of reconstruction and deconstruction of the idea, as much as the object. Buildings are sometimes the containers of impressions. When sound permeates the brickwork and you find a way of reclaiming that, or even listening to the building and reimaging the past experiences that this building has gone through, like pump rooms. I think the CCA is like a pump room. There are certain qualities of the different brickwork, or tiles – sort of an organic shift from one thing to a new thing, and becoming another thing again – I quite like those spaces.

CJ: Because you’re drawn to industrial spaces?

TM: Yeah.

CJ: And I guess, that might be partly driven by your experience of the locations where you’ve heard dub?

TM: Yeah. They’re not necessarily clean clubs, they’re sort of interesting spaces or warehouses, or churches, but through the sound being in the spaces they become another space. But then it reverts back to its original space again once the sound system moves on. I do like the idea that places are being reused and you still see fragments or details of what its past experience is, or was.

CJ: I guess there’s also an attraction to a kind of dirty sound. A sound that is not beautifully reverberating, it’s a sound that’s being interrupted.

TM: I do think there is a beauty in that, but there’s a certain richness to that quality of sound that I find interesting, and it is that juxtaposition between a clean signal or a signal that the building is sort of adding its tone to. So that mutated signal may sound differently in another space, or you’d only hear it in that context or situation. High ceilings, big places, have a different kind of quality of sound against a building that’s got a low ceiling, and you’re playing bass through that, there’s nowhere to hide yourself. The signal just travels straight through you. But in a large hall there’s sort of like dead spots where you can physically move your body into an acoustic position, where you’re not feeling the bass in your chest, or the chip is not so piercing.

CJ: So, I was thinking about those very contracted spaces where there wasn’t anywhere for the sound to go, and where it does start to fragment, and that’s what I meant by “dirty.” It becomes this gritty sound. There’s a frayed edge to it.

TM: Yeah. Also, there’s a pattern, or rhythm, to that industrial space as well. That’s another bit, like the mechanics or the machinery of that thing have a certain quality as well. Finding that pattern, the juxtaposition of that sound is an interesting space to engage with. So sometimes, you’re trying to get rid of a signal, but sometimes you actually want to embrace that, because that is the thing: the hum of the fridge, a washing machine going through its cycle, or a jackhammer digging up the road. If you play it at a certain distance, you can have a certain juxtaposition between that sound against the sound of birds, against the sound of a train, against the sound of the music on the radio, or the sound of somebody talking to you on the phone. So, there’s this sonic orchestration of all of those noises that can be interpreted as a score. That’s what I like, an orchestra of noise with industrial sound a part of it.

SC: The exhibition also features drawings and collages which span 40 years, from the early 1980s to 2022 – what was the process like selecting the works to include?

TM: It was fun to go back and look through the sketchbooks and see the technique. I love drawing on graph paper, it gives you a grid to work around. So that was fun to do again, to look at. The test was: Does this look interesting? Does it have some sort of substance? Does it pique my current interest still? And some pieces did, some pieces didn’t. My draughtsmanship may have changed now because of working more on digital things, and also still using the graphite, because I still find that interesting. I like that way of drawing, or mark-making, as much as drawing with graphite and drawing on the iPad, and the stuff that I’ve done which was drawing on graph paper, or any piece of paper that you can note down an idea on. It helped me visualise how I thought the equipment was plugged together, and also how some of the pieces could work within the space, and then there’s other elements of how I imagine the sound working within the world. I’ll give a mark to a signal or a drone and think, what’s its pathway? What would it be doing in relation to the other sounds? So that’s what I thought was interesting, to revisit that bit.

SC: Going back some years, I’d like to find out more about your involvement with the Black Audio Film Collective founded in 1982; how did the collective come about and what was the thinking behind its formation?

TM: We were all at college together; we met up in the student union bar and talked about films.

CJ: And this was at Portsmouth?

TM: Portsmouth, yeah, we were all at Portsmouth Polytechnic. On different courses, but we met up and spoke inside the union. Talked about what we’d done, and then there was different college societies, and so John [Akomfrah], Lina [Gopaul] and Reece [Auguiste], and Avril [Johnson] were part of another… I think film society. And so there were films that were getting made at different times. You know, organising film screenings of different African American filmmakers. So we started talking about what could be done, about making a film or doing a performance, which is one of the first things we did in the student union – a deconstruction of Aimé Césaire, using cut-up techniques, by building the soundtrack. It was a very strong, disrupted sort of performance piece, and I think that was one of the first things we did.

CJ: And who did that?

TM: There was John Akomfrah, Lina Gopaul, Avril Johnson, Reece Auguiste, Edward George and Claire Joseph. So basically, we had the text, the text was cut up so people had different features to read, and that was going through a reverb and echo. And then I built this soundtrack, which was a heavy, rhythmic, sort of piece. Sub bass was built at the back of the hall where we put benches so people literally could sit on top of the sub bass. And then we had projections of archive photographs projected across the room on top of muslin. It was translucent, but it created this layered effect, so there were different people standing in different parts, either in front of the screen or beside. And there was a very tonal reading of this piece.

CJ: And so that was staged as a performance?

TM: Yeah, we invited people in to come and watch it.

CJ: Was it part of something else?

TM: It was for one of those festival-type things, and we said, “Okay, we’re gonna do something,” and we did it in the student union. What I liked about it is that it’s spoken word, and sound, and visuals all sort of coming together. That was pretty cool.

CJ: What were your other influences, do you think, at that time?

TM: I was influenced by becoming more aware of noise. You could literally play with that as an area of investigation or as a sculptural tool. Also, I realised, giving myself permission to experiment with this medium, this sound, and not to feel like this is not yours to play with, and not yours to investigate. So that was one of the sparks, giving oneself permission to make a particular kind of sound that normally is not seen as your area of interest. And to bring all of these interests together. I loved the staging because it looked like this gossamer-like screen with these figures dissolving, because it’s like a tape-slide sort of thing was going on the images. So it’s on the dissolve. So that had a rhythm, then there were people doing the reading. Each person had a different part to read, and it was subject to effects and then the soundscape that they were doing it through was coming from the back of the hall to the front with this low frequency rhythm and tone. All of this energy came together into this one off performance. And then we thought, “Oh, we can do this,” and then the conversation became about doing more.

CJ: So that was the inception of the group, that performance?

TM: Yeah.

CJ: What do you think were the factors that meant it was that particular group of people that came together at Portsmouth at that time?

TM: It was a good mix of people who were asking questions and listening and debating, and engaged with a cross platform of ideas and influences. We all had the interest in doing something. Making the cultural product. And it felt right to do this.

CJ: When those conversations started happening about “We could form a group,” how were those?

TM: It was talking about it and working out what kind of model would work, and the collective model seemed to be the right one for us at that time. And there was support from the TV unions and the Greater London Council. There was a time where collective practice was recognised as an acceptable way of working in the arts. And so that’s the thing that we went with, because it was right for us. Each of us had a different skill base and we thought we would benefit from sharing that pool of information or ideas, and then using it to make films.

SC: What are you currently reading?

TM: Manuals. A Manual on the Polstar 23, a manual on the Nikon Z6, and there’s a few others. Manuals are my go-to at the minute. Just understanding how the kit works and how I can integrate it into my practice better.

Trevor Mathison’s From Signal to Decay: Volume 1 runs until 18 September 2022 at Goldsmiths CCA.

Feature image: Installation view, Trevor Mathison, From Signal to Decay: Volume 1 at Goldsmiths CCA. © Trevor Mathison, 2022. Photo: Rob Harris