On The Origins & Evolution Of Carnival With Curator Habda Rashid

By Something CuratedOpen now and running until 19 February 2023, Kettle’s Yard presents Paint Like the Swallow Sings Calypso, a major new exhibition curated by Habda Rashid in dialogue with Barbadian artist, educator and writer Paul Dash, Jamaican artist and editor Errol Lloyd, and Trinidadian poet, artist and curator John Lyons. Alongside a selection of their own works, the artists bring together the collections of Kettle’s Yard and The Fitzwilliam Museum for the first time, assembling paintings and works on paper that reflect the rich history and themes of Carnival, from street parades and dance, to folklore, flora and fauna. The work of 28 artists spanning five centuries reflect elements from Carnival’s rituals and celebrations, including Jean-Michel Moreau, Albrecht Dürer, Helen Frankenthaler, Avinash Chandra, David Bomberg, Graham Sutherland and Barbara Hepworth. To learn more about the ambitious exhibition and Carnival’s fascinating history, Something Curated spoke with Kettle’s Yard and Fitzwilliam Museum curator Habda Rashid.

Something Curated: Tell us about the exhibition you have curated in dialogue with Errol Lloyd, John Lyons and Paul Dash.

Habda Rashid: I joined Kettle’s Yard and the Fitzwilliam Museum just under a year ago, and as part of taking my joint role, I was asked to curate an exhibition that brought together works from each of their respective collections, something, surprisingly, that had never been done before. I wanted to take advantage of being new and, in a sense, a bit of an outsider when it comes to existing narratives and ideologies within the institutions and collections more generally. I am also really thinking about how we can create a dialogue between the Western Canon, and what some might call ‘traditional’ framings of art history to incorporate other stories of art. I feel we have gone through the looking glass in terms of thinking that there is a singular understanding of the genealogy of art. Therefore, I really wanted to re-think or re-look at how we can read the collections’ works we present – a ‘differencing’ which is a term that art historian Griselda Pollock uses.

I had been to the studios of both Paul Dash and John Lyons, and was struck by their engagement with Continental traditions in art, and by how much I felt their work could speak to the collections. It was also noticeable that both examined or worked within the context of Carnival. They were telling stories whilst making sense of their own lives transcending the Caribbean and the UK. I subsequently invited Errol Lloyd to join, and we set about creating an exhibition framed around Carnival, drawing connections between the collections and the artists that reflect the festival’s history and themes. Another layer I added was to connect both collections by including artists such as Graham Sutherland and David Bomberg (from the Fitzwilliam), who were producing work at the same time as the artists Jim Ede collected for Kettle’s Yard, such as Ben Nicholson, Barbara Hepworth and William Congdon, who are all in the show.

It is important to note that the sense of Carnival we have worked within is syncretic, anti-colonial and fluid to temporality. The best way that this is described is in the writing of Wilson Harris, whose quotes are used in the show. I met with Paul, Errol, John and Guy Haywood (Assistant Curator at Kettle’s Yard) bi-weekly for about 3 months to talk through works in the collections and choose pieces for display, by far the majority of which were chosen by the artists themselves. Overall, there are two parts to the show: a historical presentation of works mainly loaned from the Fitzwilliam, which explore different celebrations linked to Carnival; and then a Carnival mise-en-scène in the second room. The 3 artist-selectors’ works are placed throughout, in dialogue with those from the collections.

SC: Are you able to expand on the origins of Carnival and its relation to the history of enslavement?

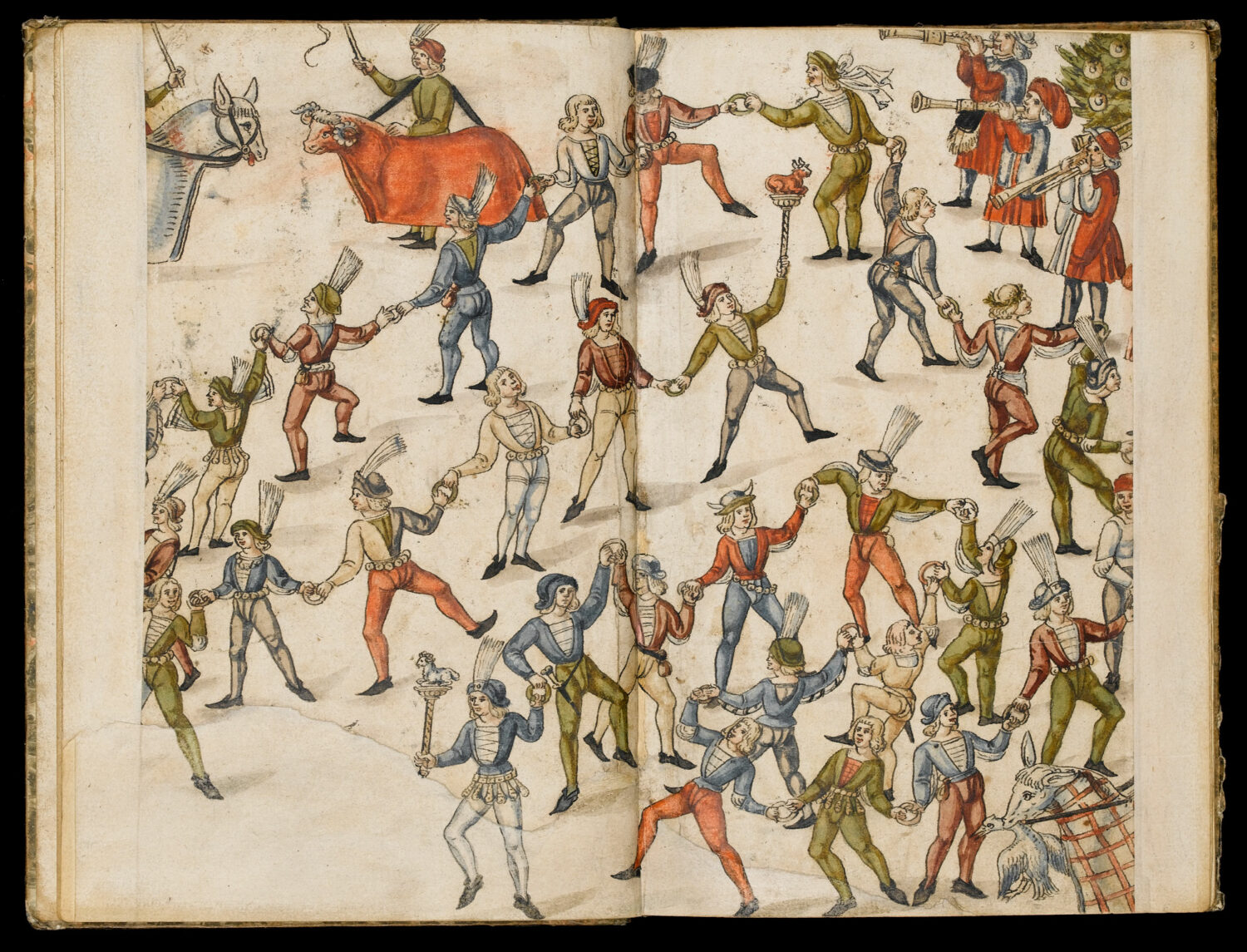

HR: Carnival’s entangled genealogy can be traced to pagan rituals including the festival of Sham El-Nessim in Ancient Egypt, which was celebrated to usher out winter spirits and announce the beginning of spring. It also has roots in pre-Christian European festivals such as Bacchanalia, a Roman festival of Bacchus, the Greco-Roman god of wine, freedom and ecstasy dating back to second century BC. The dominance of the Church of Rome meant the early celebrations were adapted to become festivities around Ash Wednesday (thus Mardi Gras) to pay farewell to vanity and the lust of the flesh, before entering upon the period of fasting and repentance during Lent. In the Carnivals of Catholic European countries, donning masks and characters’ costumes (such as the Harlequin) became the norm. Evolving from these traditions were extravagant and exclusive masquerade balls, which travelled with European colonisers to the Caribbean.

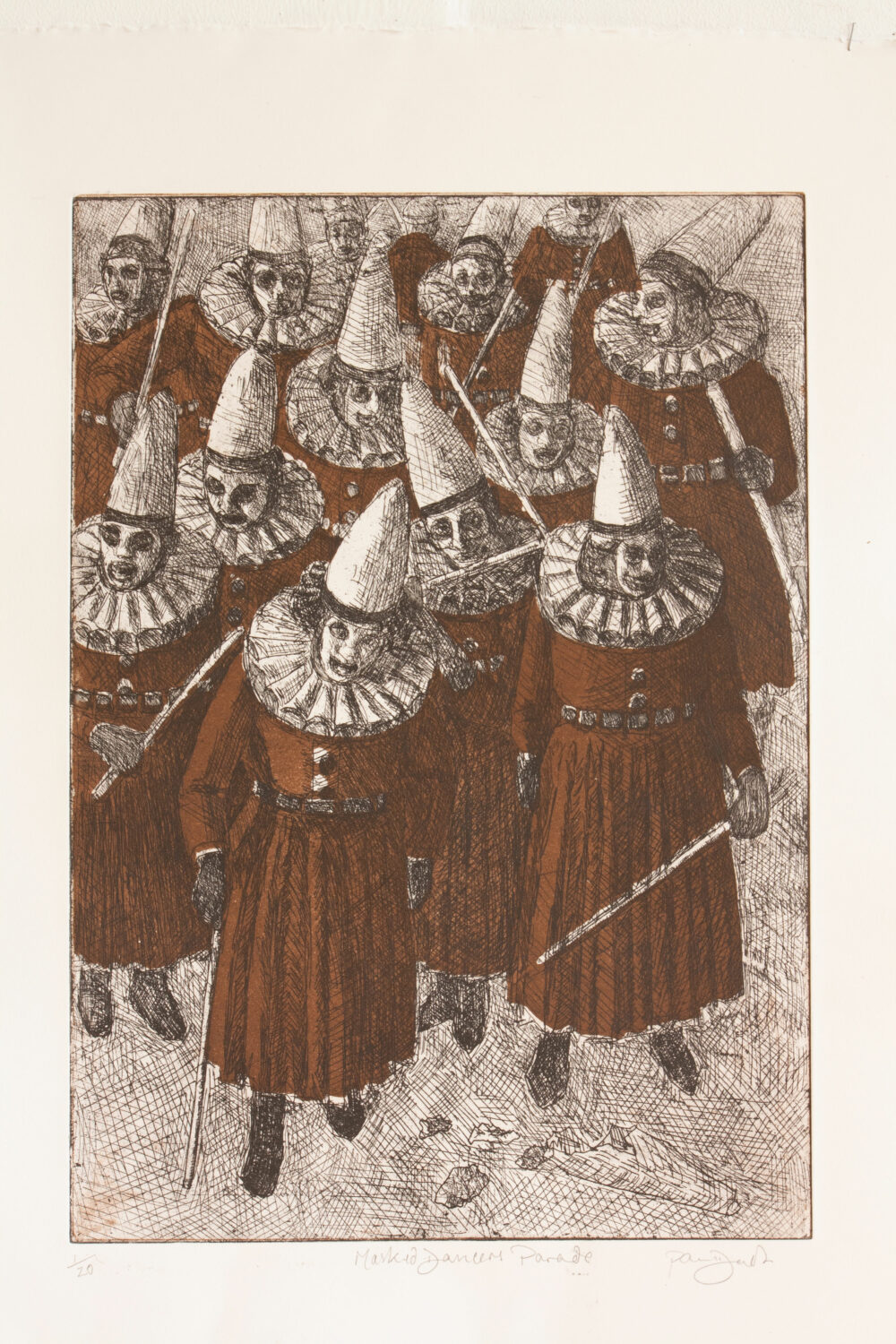

During the colonial period in the Americas, Carnival celebrations and street parades were common, but they were segregated between the European settlers, and enslaved and Indigenous populations. What we understand as Carnival today has developed from African and Amerindian culture, in relationship with and in struggle against European customs after the late 1800s and emancipation. In a sense, Carnival became a joyful celebration of freedom, without forgetting the past. In Paul Dash’s Masked Stick-lick Fighters Parade, for example, he depicts costumed figures performing kalenda, a martial art and dance derived from Africa and transferred to the Caribbean by the enslaved. Men would duel with sticks to the rhythm of kalenda songs, which were angry, chantlike and rebellious, offering a release of tension from slave conditions, but now subsumed as part of Carnival celebrations. The Soucouyant, too, the Trinidadian folkloric shapeshifting vampire, is related to the Transylvanian Dracula, and an example of how customs have been absorbed and modified. The Carnival we recognise today still embodies a deep association with the enslaved and African traditions.

SC: Could you talk more about the impact of the Caribbean Artists Movement in the UK and beyond?

HR: We are beginning to acknowledge the significance of the Caribbean Artists Movement (CAM) today, but I feel we must recognise that the Movement originated because of a lack of opportunities that existed for artists of colour at the time (1966-1972). It was a short-lived movement due to funding, and several artists either stopped making work or struggled for several years. A few also left the UK entirely. It was a particular moment in terms of the historical and social backdrop of the mid-1960s, with the recent attainment of political independence by many former British colonies, not only in the Caribbean, but also in Africa and Asia. Many of those involved had only recently arrived in the UK, so there was a real sense of transnationalism in their work and ideas. For CAM, ‘art’ had a broader meaning, and the group included academics, artists and writers, three of which – John La Rose, Kamau Brathwaite and Andrew Salkey – founded the Movement.

I feel that the paintings of Aubrey William really speak to this contemporary moment as, at the time, he was concerned with the environmental destruction of the Guyanese forests, pointing to the effects of colonialism, which he successfully imbued into his works through fast and violet brush strokes and speckling. He also wanted to move away from Western art history, not in an overtly antagonistic manner, but he instead examined traditions linked to Indigenous cultures. Today this is a direction that many artists and curators are taking, an example of which is this year’s iteration of dOCUMENTA. Errol Lloyd was very much part of CAM and it’s such a privilege to work with him and listen to him talk of those times.

SC: How have you considered utilising the Kettle’s Yard space as a site of display?

HR: The show exists in two parts, in both gallery spaces at Kettle’s Yard. In the first we present works that reflect the historical trajectory of Carnival through European traditions that, through colonialism, were taken to the Americas or have a relationship to Carnival as we know it today. These etchings, prints and drawings showcase Bacchanalia, masquerade balls and imagery relating to commedia dell’arte that has its origins in early Italian Carnivals. These works are placed in dialogue with Paul Dash’s pieces; his Carnival scenes act as memory images, with fine lines and sepia tones which, although bright, seem washed away. This is his way making sense of his own ruptured history, while also acknowledging the impact of colonialism in terms of the Caribbean and, more specifically, Barbados where he is from. With the work Masked Stick-Lick Fighters Parade (2019), Dash notes that his ‘”fighters’ are dressed in gowns, high pointed hats, ruffs and white masks as well as armed with sticks. My intention here was to signal a cultural period that extends historically to Elizabethan times, and the expansionist arrival of Europeans in the Americas … The sticks imply the Stick-Lick martial art form that developed on the plantations in the Caribbean during the period of enslavement and colonialism and here, symbolise a determination to strike back against racist aggression.” We all felt it was important that the exhibition reflected the troubled history if Carnival and its connection to the Trans-Atlantic slave trade.

Mirroring Carnival’s blend of mythologies, religions and perspectives, the second gallery space features modern and contemporary and modern works from the collections alongside paintings and woodcuts by John Lyons and Errol Lloyd. This display considers the symbolic and spiritual aspects of Carnival through abstraction and surrealism in order to create an imagined Carnivalesque ‘mise-en-scène’. This section offers new ways of contextualising the works, beyond European art historical conventions. Magico-religious scenes are presented, including David Bomberg’s subdued and abstracted Spanish candle-lit procession during holy week 1935, which is displayed with John Lyons’s Eloi! Eloi, its straining crucifixion sceneechoed in the knottedfigures depicted in Graham Sutherland’s vibrantly painted Deposition.

Exploring philosophy through his art, Avanish Chandra in Design transmutes his female forms beyond flesh to imbue ‘other poetic images: spires, trees, flowers, hills, moons and stars. While John Lyon’s Obeahwoman, ghost-like, heralds the importance of Carnival to Caribbean societies, for which the Obeah Woman was a leader and teacher of African folk’s cultural heritage. Helen Frankenthaler’s luminous colour-soaked Abstraction, inspired and informed by landscape, is a lens by which to view nature in our Carnival world and leads to the final work in the exhibition: Lloyds’s Notting Hill Carnival – 11C. This large-scale finale distils the sensory adventure unique to Carnival through an interplay and balance of abstracted blocks of colours with highly patterned representations of Carnival goers.

SC: What is the thinking behind the show’s title, Paint Like the Swallow Sings Calypso?

HR: This exhibition’s title references The Mighty Swallow, the performance name of Antigua and Barbuda calypso musician Sir Rupert Philo (1942-2020), whose lyrics protest the inequalities inflicted upon enslaved Africans and Indigenous populations under colonial rule in the Caribbean. The Carnival we recognise today still embodies a deep association with this period, with many of its recognisable customs and rituals adopted from slave traditions including bamboula dancing and drumming, and Kalinda (stick fighting) as depicted by Paul Dash. There is also a nod to poetics and the lyrical gesture of a brush stroke.

SC: And what do you hope to achieve with this presentation?

HR: I hope to give a platform to three important artists, Paul, Errol and John, and to showcase their work – and each of their idiosyncratic perspectives – in step with the collection artists that they will be displayed next to. In this way, I hope to create an imaginative art historical (and ideological) dialogue. The show also tells a story about Carnival, which is something that audiences will recognise, but perhaps not fully understand its history. More generally, I’m interested in creating relationships within collections and bringing more historical works into Kettle’s Yard from the Fitzwilliam. Paint Like the Swallow Sings Calypso includes 28 artists spanning nearly five centuries. My research and curatorial practice are centred on re-looking at art histories to fully embrace the varied global genealogies of cultural and creative production. I feel we are at a pivotal and exciting moment where we can make displays that point to narratives beyond those re-told in canonical art history and subvert the notion of a modernist project. Saying that, I’m very audience driven, so I’m also keen to make a show that the public finds joyful and insightful.

Feature image: Errol Lloyd, Notting Hill Carnival – Aztec, 1997. Courtesy the Artist