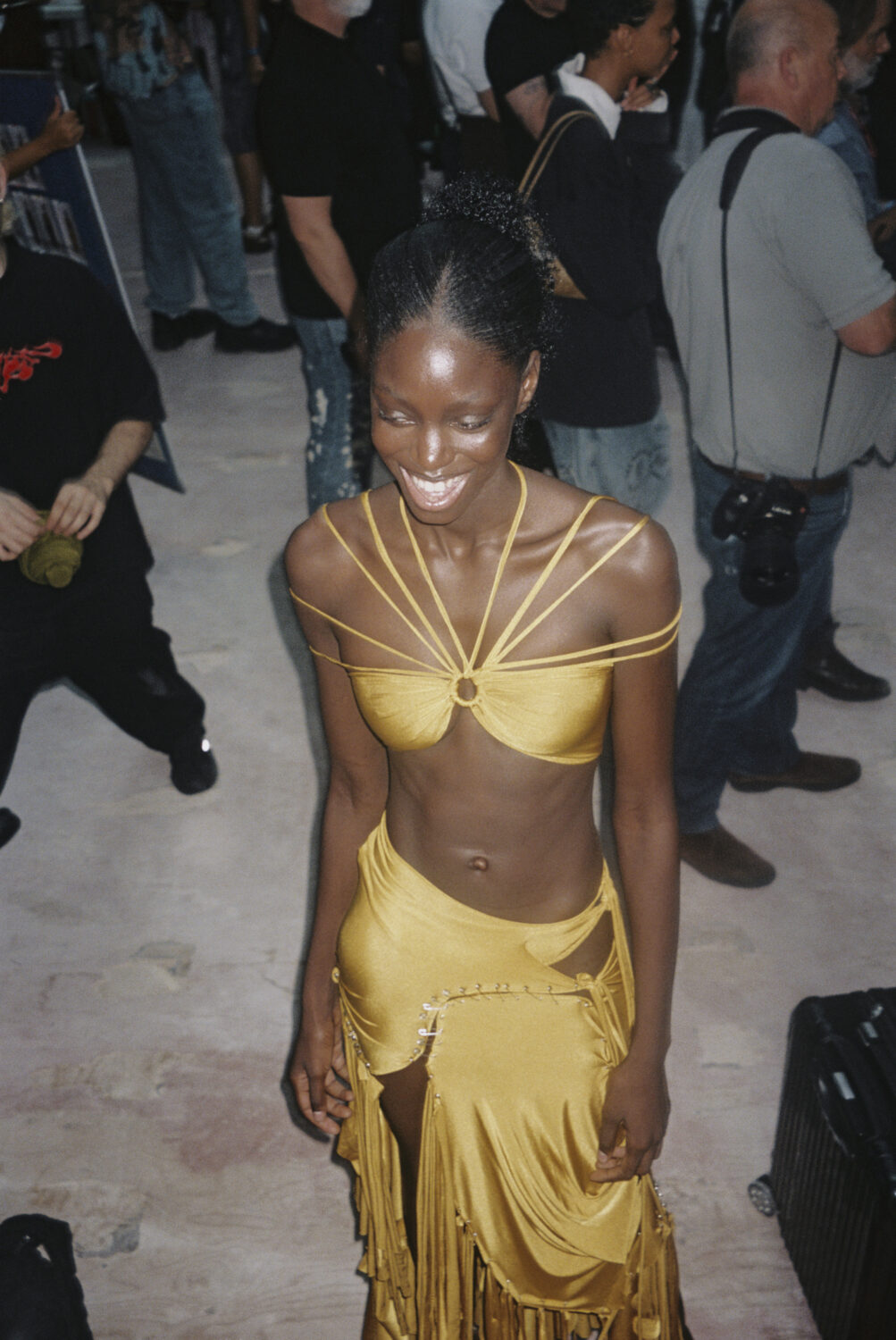

Interview: Jamaican-Caymanian Designer Jawara Alleyne On Radical Materiality & Island Life

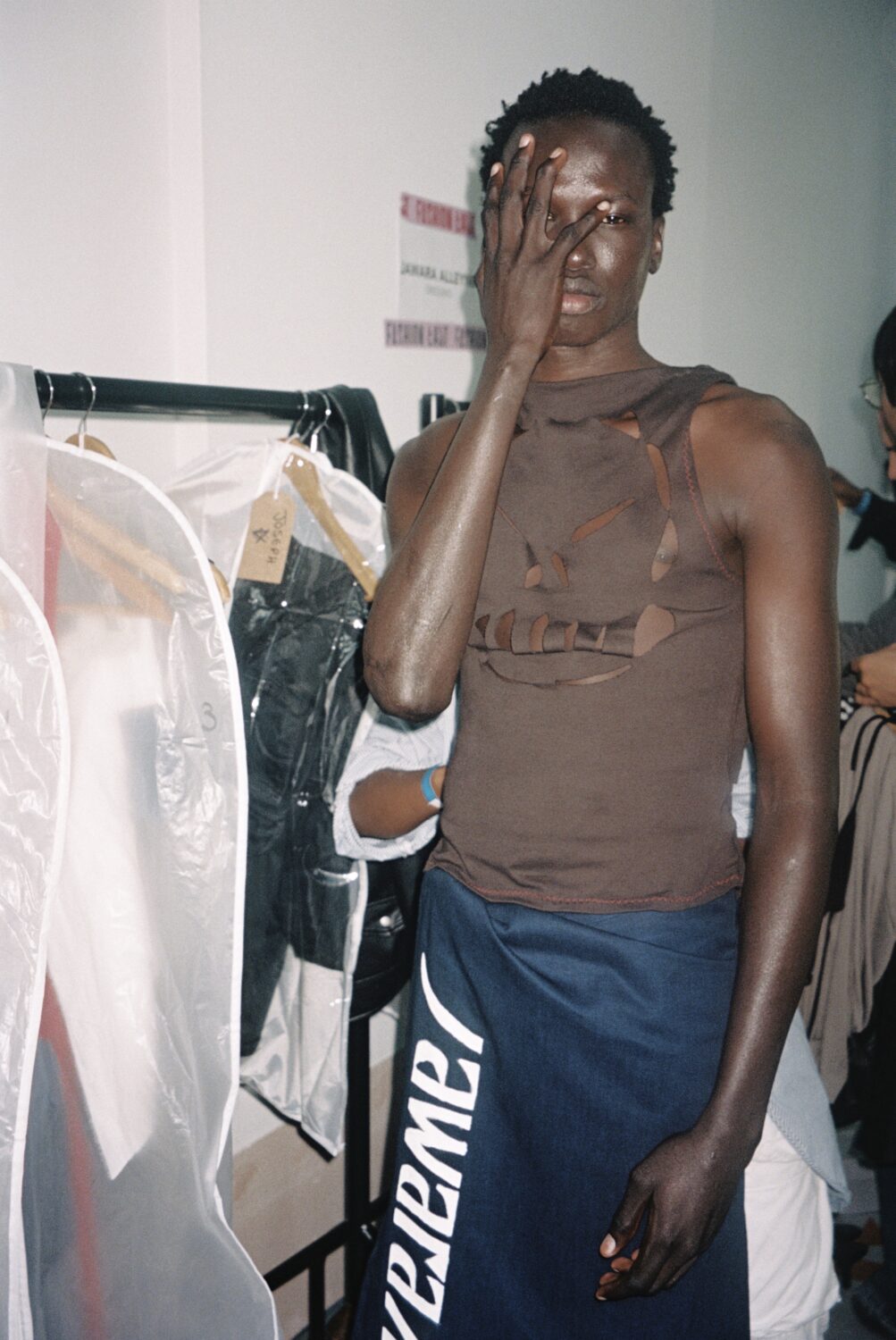

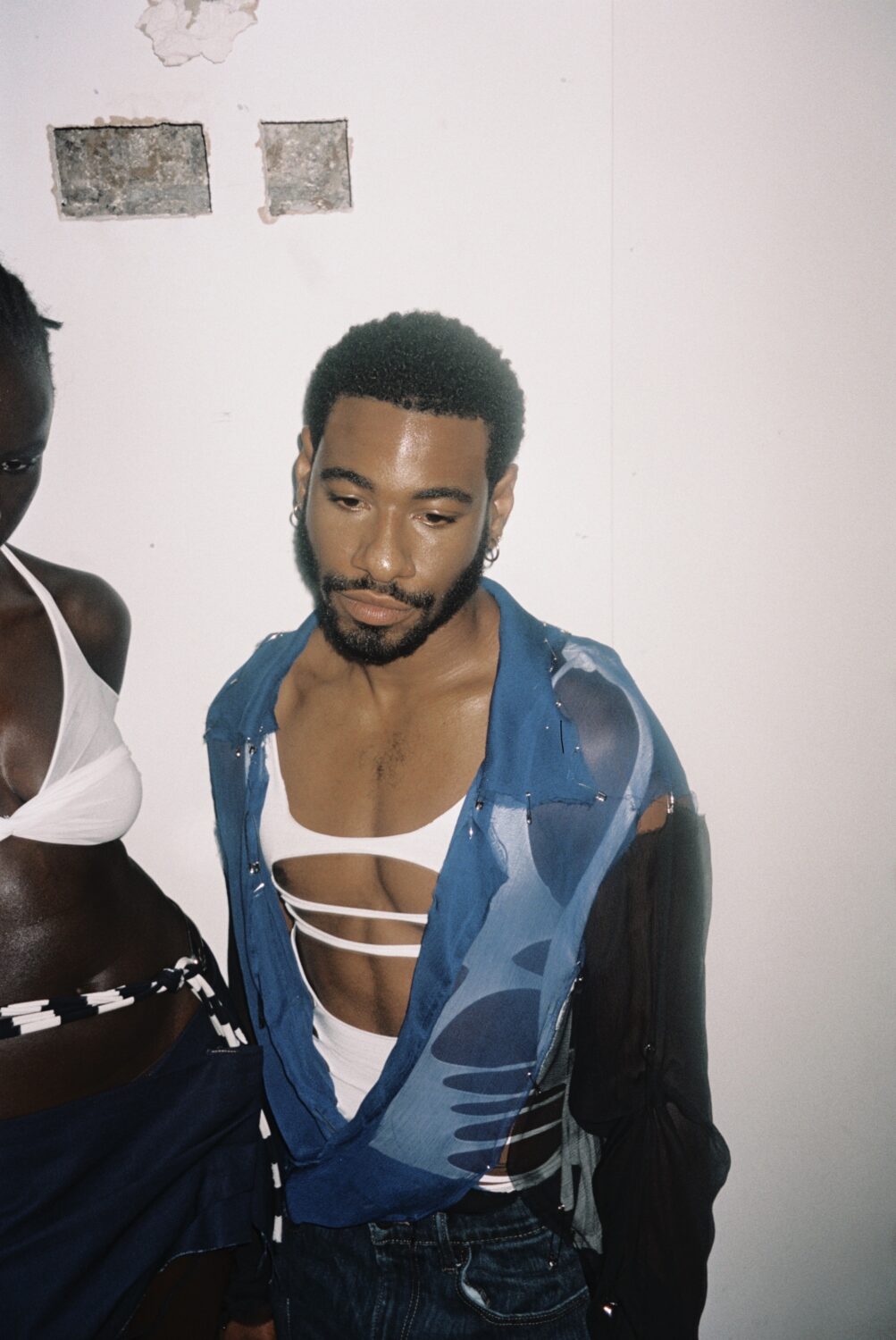

By Something CuratedShaped by his experience growing up between Jamaica, the Cayman Islands and the UK, Jawara Alleyne’s interdisciplinary practice seamlessly oscillates between the realms of art and fashion. Through a nuanced amalgam of Caribbean mythologies, including the Rastafarian mysticism of Jamaica and the pirate folklore of the Cayman Islands, contrasted with the histories of London’s subcultures, Alleyne weaves stories that meander through the present and the past, ultimately navigating new futures. The designer graduated from a Masters in Fashion from Central Saint Martins in 2020 and is presently supported by the Lulu Kennedy driven initiative Fashion East, showing his work at London Fashion Week. Alleyne’s most recent collection, ‘The New World,’ is characterised by sumptuous draped silhouettes, slashed textiles safety pinned back together, and a kaleidoscope of colour combinations inspired by the designer’s roots. To learn more about Alleyne’s work, his influences and what he has planned next, Something Curated spoke with the designer.

Something Curated: Can you give us some insight into your background — how did you enter the field of fashion?

Jawara Alleyne: I was born in Jamaica but grew up in the Cayman Islands and have always been into fashion as a kid. I’m known by pretty much everyone that knows me from both islands to have always had a little sketchbook with me for drawing. It was really therapeutic for me I think as I channelled a lot of my anxieties in the art form. When I was in the Cayman Islands I did a lot of art programmes, pretty much every one that existed while I lived there. Notably there was one called Fresh Cayman Couture. It was here that I really started actualising my interest in fashion, developing full collections.

I did my first runway at the age of 16 and since then was involved heavily in the fashion and art community in the Cayman Islands. I was essentially forced to study business by my mother as the last resort to sway me from going away to study fashion however that only provided key skills needed to take the next step in becoming a designer. At the age of 19 I moved to London to study at the London College of Fashion and since then have worked for Peter Pilotto, working on projects for Beyoncé and Princess Eugenie; and after this, I went onto graduate from an MA in Fashion at Central Saint Martins. I started my brand officially right after that in the year 2020. The year the world stood still.

SC: You’ve already carved out a very particular aesthetic through your tactile use of cloth — how would you describe your approach to utilising material?

JA: I think my approach to materialism comes directly from having grown up in the islands. When I was in Jamaica I grew up with a Rastafarian background, which came with a deep relationship with ways of thinking about materials. In the culture the wrapping of dreads is a significant act and I think having observed this relationship to fabric gave me an almost holy way of thinking about fabric. Growing up in the church also further deepened that relationship to materials. I was obsessed with the Shroud of Turin as an object as it was so simple yet so significant. Growing up on the islands, there was always a huge culture of wrap tops, dresses and skirts, scarves used to make tops and skirts and even wrapped towels on the beach. I guess this added to the importance of that resourceful point of view because garments that focused on the properties of the material itself always surrounded me. The culture was very resourceful.

I think my radical use of materialism though is something that’s quite innate. I’ve pulled from my background and culture however the hand that I have and what the hand does when it touches fabric is something that I’ve always shied away from in favour of developing practices that aligns with an industrialised view of fashion. I learned that things needed to be perfect to be valuable even though my hands didn’t really want to do that and the feelings in fashion that I always gravitated towards said otherwise. I always gravitated to radical points of views, DIY culture, punk ideologies, even anti-fashion. It took me a really long time to be confident and comfortable with my own way of approaching materialism and to recognise the value in that.

SC: Could you expand on your interest in storytelling through garments?

JA: Storytelling is something that I’ve always learned, particularly growing up in the Cayman Islands and further Jamaica. Our cultures are oral, to the point where we have this really important festival called ‘Gimistory’ (which really doesn’t get the recognition it deserves). Caribbean people and a great many other peoples around the world, we share our POV’s and our stories in an oral way. Think of how Black people dominate the music space with their intricate ways of storytelling and weaving words into something of great value. In very much the same way, for me there’s a huge value and importance in storytelling because my culture captures history, teachings, and philosophies through oral storytelling.

I’ve used storytelling as a kid to dream up other worlds and to navigate the complicated Caribbean spaces and to be honest storytelling has even allowed me to find my new sense of identity now having lived in London for more years than I lived in the Cayman Islands for. For too long we were never in charge of telling our own stories and to this day we still aren’t the narrators of our own stories. I use fashion as a reflection on this. Fashion itself is the greatest form of storytelling we have as people because it allows us to say exactly who we are or who we want to be through the things we put on our bodies. It’s the greatest tool of communication we have.

SC: How was Nii Agency born; and how do you see the project evolving?

JA: Nii agency was born in the library at Central Saint Martins. I was writing my dissertation with Campbell Addy sitting beside me and he shared an idea he had that he was a bit hesitant about. He disclosed that he always wanted to start an agency and that in the past year he’d realised that his experiences within the industry proved that it was kind of needed. I looked at him with a straight face and said, I owned a modelling agency right before I left the islands and that if he really wanted to do it, I’d be there 100%. And from that conversation Nii agency was born. The idea came in a moment of hesitancy but I think from then on, things just moved, as we were both on the same page. I understood the importance of Campbell’s vision, as it was a vision that I shared. Unfortunately I had to step away from the project to focus on my own fashion practice but Nii lives on through all of Campbell’s projects and to some extent my own as well. It was never just an agency but more of a point of view and a way of thinking about the future of fashion. We knew that things needed to change. We also knew that we had to be the change. Industries and systems don’t change unless people do.

SC: Are you able to tell us about what you’re presently working on?

JA: At the moment I’m focused on my own fashion and art practice. Running my brand from London, which has just seen us show our SS23 collection at London Fashion Week. The collection was called ‘The New World’ and actually spoke directly to this idea of being in charge of writing our own narratives. I’m also working on my WIP collection ‘Untitled’ which drops bi-weekly on my web-shop, a zine, some music, a film, the next show and in general building the brand. It’s never ending when you’re starting a creative practice as every day is filled with bringing to life any ideas that come to mind, while also building a sustainable business alongside that, while also trying to navigate the chaos of a crumbling world. It’s very surreal and takes a sheer amount of cognitive dissonance.

SC: And what are you currently reading?

JA: Right now I’m reading Charlie Porter’s What Artists Wear. Such a great book as I’m obsessed with the psychology of people, how they think about themselves, and how this translates into what they choose to put on the body.

Feature image by Jebi Labembika