Interview: Ian Cheng On New Ways Of Filmmaking & The World Beyond The Narrative

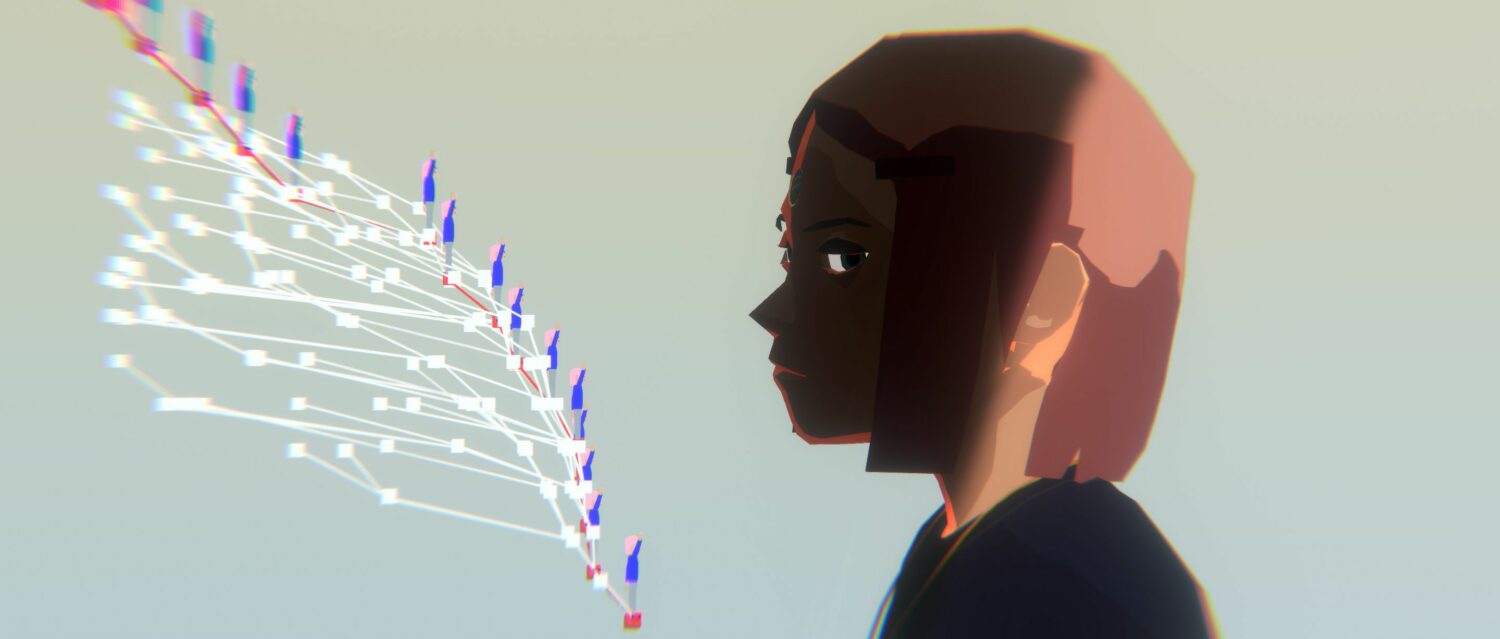

By Keshav AnandHailing from Los Angeles and presently based in New York, artist Ian Cheng’s fascinating work investigates the nature of mutation and the capability of humans to respond to change, resourcefully drawing on principles of videogame design. Having had major solo presentations at the Leeum, Samsung Museum of Art, Serpentine Gallery, MoMA PS1, and the Migros Museum, among other eminent institutions, Cheng’s practice has garnered acclaim for its highly innovative approach. First came the Emissaries trilogy, which introduced a narrative agent whose impulse to enact a story was set into conflict with the open-ended chaos of the simulation. Then the artist developed BOB, an AI creature whose personality, body, and life story evolved across exhibitions. More recently, Life After BOB: The Chalice Study introduced the character of Chalice Wong, a young girl whose father installs in her nervous system an experimental artificial intelligence, the aforementioned BOB, to guide her through the challenges of growing up. To learn more about Cheng’s ambitious work, his journey into the art world, and his upcoming exhibition at London’s Pilar Corrias gallery, Something Curated spoke with the artist.

Something Curated: Can you give us some insight into your background and journey to art making?

Ian Cheng: I studied Cognitive Science at Berkeley, graduating in 2006. I studied a lot of AI on paper, in a theoretical sense – but there was actually nothing real about it, no computers, no GPUs. There were no jobs I could imagine taking in Cognitive Science so I went to work at Industrial Light & Magic, which is George Lucas’s special effects company, and then shortly after that I went to Columbia to pursue my MFA in Visual Arts. I was very confused and young and thinking, well if I study art, I can figure out a way to choose my own problems. After I graduated, I worked for two artists whose work I really loved, Paul Chan and Pierre Huyghe. Particularly from Pierre, I understood what it felt like to be an artist. Like what time he woke up, what exercises he did, what he had for breakfast, how he structured his time, how he learned to say no to things. All that helped give me a very visceral sense of what it took to be an artist. In 2011, after working for Paul and Pierre for about a year and a half, I started making my own work.

SC: Following the Emissaries trilogy and BOB, how was Life After BOB: The Chalice Study born – can you tell us more about the work?

IC: After Emissaries, I showed BOB, Bag Of Beliefs, at Serpentine; this was an AI driven creature. Emissaries were these big simulations with a lot of characters and a lot of things that those characters could interact with in a big landscape that would evolve and change over time. And with BOB, I wanted to focus on a single character and its brain. So BOB began at Serpentine and the AI model evolved over the following year. After BOB finished, in around 2019, my wife and I were expecting our first kid – we have two kids now – and I just thought, I am going to make it easy for myself. I am going to put AI aside, BOB is so hard to make, gratifying but extremely hard, I’m going to do something easy like an animated cartoon. It turned out to be the hardest thing ever, mostly because stories are really hard, making children’s media is really hard, and I realised, even though the production process of making a cartoon is really well known, I couldn’t do this the normal way. I had to do it in the Unity game engine, which is how I made all my previous work.

So we have to be able to produce an animated cartoon in this unorthodox way. Why? Because animated cartoons are very expensive to make and as a director, once you start down a path in animation, its very expensive to say, “Oh, I don’t like that scene,” or “Oh, I didn’t like the way that character walked, let’s change it.” But as an artist, I’m so used to changing my mind. And I thought if we make it in Unity, like I’ve always worked in, it renders in real-time, we can code something a little differently, we can shift things in the virtual scene – you can basically be both a director and an artist who can’t make up his mind at the same time. So that’s how Life After BOB came to be. Production started around March 2020, so it was kind of a pandemic project. It turned out to be a 50-minute long animated film – I think the longest ever done in the Unity engine. It can play in real-time, and that’s how I have been presenting it. And when presented in real-time, I am able to change things in the background of scenes so each time it’s slightly different.

SC: Why is the “Worldwatching” element important to you – and can you talk about it in relation to narrative media?

IC: The feature allows you to pause the film with your phone, just like you would with your remote control on your TV at home. But you’re not just pausing it, you can actually highlight and click on anything in the background and zoom into it and then suddenly the film also turns into a way to explore the world that the film is presenting narratively – you can go deep into it. So you can click on anything and it brings up all the Wiki data, all the mythology about the background object. You can learn more about anything you see that you find interesting, even if it’s not maybe pivotal to the plot. I always loved in movies like in Alien or Blade Runner, or Spirited Away, where there is all this amazing stuff going on in the background, all these crazy characters. And I always thought as a kid, I wish I could pause it and go into that turtle guy’s world. Like, what does he have to say? Where does he come from? Of course part of the mystery and beauty of it is that your mind fills it in but I always thought, Miyazaki probably has a backstory for that guy – somewhere he’s made notes about it. What if you could actually explore the world beyond the narrative?

My daughter was around two when Life After BOB was still in production – I would read her this book called Big Red Barn. It’s a super simple story about barn animals having a nice day and then going to bed at night. She loves the pictures but she got super bored with the story after like five times, and she would stop me on a page and she would point to the little mouse in the corner and say, for example, “I want the mouse to eat the egg. What’s inside the egg? What if the cow ate the egg and pooped and then the chicken ate the poo?” You know, just kind of riffing. One thing she said to me once was, “Daddy, stop reading. Eden go in!” Her name is Eden. She wanted to go into the page, she doesn’t want to go left or right, like a linear story, she wants to go into this freeze-frame of this one scene and explore the characters on this one page. I thought, wow, if I had the imagination of a kid now and I assumed that you could do that, I would really want to be able to experience that from the media that I’m looking at. I realised its an impulse that I still have even as an adult. The spinal cord is the story but what if the thing that makes you stay is that you can just keep on going in, in, in? I’ve been kind of obsessed with this idea.

SC: Are you able to offer some insight into working with the Unity game engine and how the work can be presented live in real-time?

IC: The Unity game engine is kind of like the Photoshop for videogame making. Its main capability, I would say, is that it can render things in real-time, in the same way that a videogame renders in real-time. And why it has to do that is because things are always changing in a videogame. Even the simplest videogame on an iPhone is a dynamic system that’s constantly responding. When you apply it to something more cinematic – I think we take for granted that films run in 24 frames per second – once you can do that in a videogame engine, you can start to stick in all the other videogame stuff that you never stick into an actual film.

Another interesting aspect about this way of working is, we traditionally make updates of movies by creating whole new versions – I don’t know how many Batman updates there are at this point. But then there’s always this nostalgia – I recently saw a trailer for a new The Flash movie, which brings Michael Keaton, the original Batman actor, into the story in like a cameo. There is obviously this pleasure and desire that people have in sticking with the original material in a way but seeing it rejigged. Well maybe you can do that in the future – you just work on the original film and start playing with it but you have all the characters, the voices, they are all still there. So the things you really love are still retained but maybe you see them in different scenarios, or experiencing different endings.

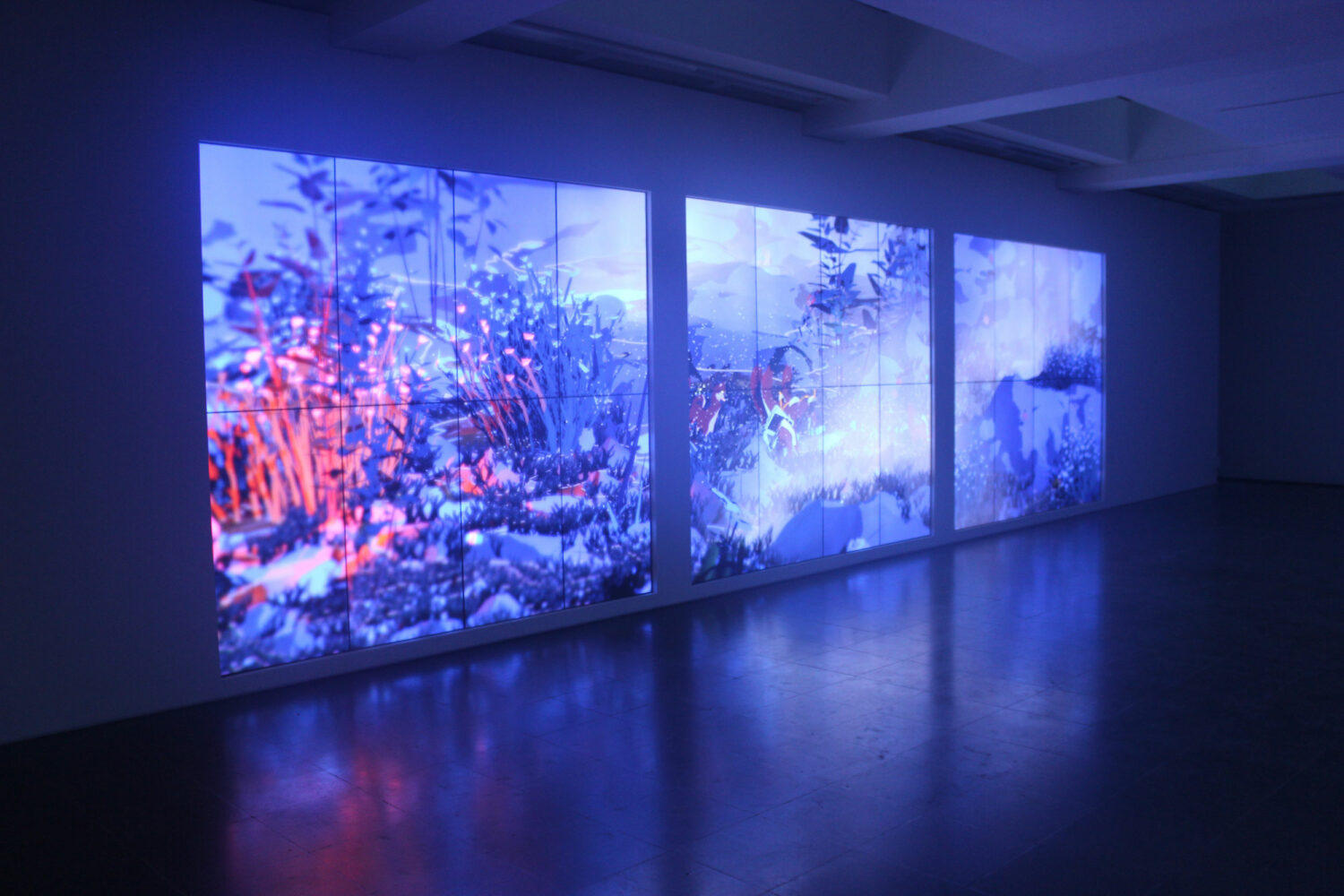

SC: Can you tell us about the new animations at your upcoming Pilar Corrias exhibition?

IC: Downstairs, we will present Life After BOB. For me, this is almost like an anchoring project. It’s a 50-minute work and I think it’s quite a commitment from a contemporary art exhibition point of view to ask a person to sit through something like that narratively. It requires a certain attention and focus. So alongside it, upstairs I’m showing – it still doesn’t have a name yet – this turtle, a very minor character in Life After BOB. In a key scene near the end, Chalice discovers this turtle, which is a biological turtle in the film but it’s also this kind of memory hard drive of all the life that BOB has lived for her and she uses it to sort of reconstitute herself near the end of the film. But of course it is also a turtle, so it’s like a pet and a hard drive at the same time. Life After BOB is very long and dense with narrative, that’s a normal story, and I thought there is something else I could do here – something I started to call the slow story.

Something more than a screen saver but less than a full-on narrative film. I thought if you could watch the routine of the turtle, this innocuous little animal, so slow, probably has a pretty boring life, aside from the sci-fi elements – you could watch, be bored of it, maybe you like the details of it, like maybe the turtle walking through carpet, there’s a feeling to that – you could start to become enthralled by the micro-dramas of the turtle’s life. For example, the turtle is going across the room for a piece of food – will he get it? It’s clear sailing and then Chalice bursts in like a force of chaos and drops a big bag in front of him. His whole world is fucked and now the AI has to resolve this upset. But 90% of the time, it’s a slow story of daily routine with these tiny little satisfactions. I basically wanted to slow down the temporality of something from the Life After BOB world.

SC: What are you currently reading?

IC: Mastering Jujitsu by Renzo Gracie. The Gene Keys by Richard Rudd. What’s Our Problem by Tim Urban. And I’m always reading this one Substack called Ribbonfarm Studio by one of my favourite writers and thinkers, Venkatesh Rao. I’ve been reading his blog for years.

SC: Favourite cultural space in New York?

IC: I’ve fallen into a Brazilian jiu-jitsu hole and I love going to classes at this place called Workshop on Delancey Street. For me, this is kind of like going to temple.

Ian Cheng at Pilar Corrias, London runs from 2 March – 6 April 2023.

Interview by Keshav Anand | Feature image: Ian Cheng, Life After BOB: The Chalice Study, 2021. © Ian Cheng