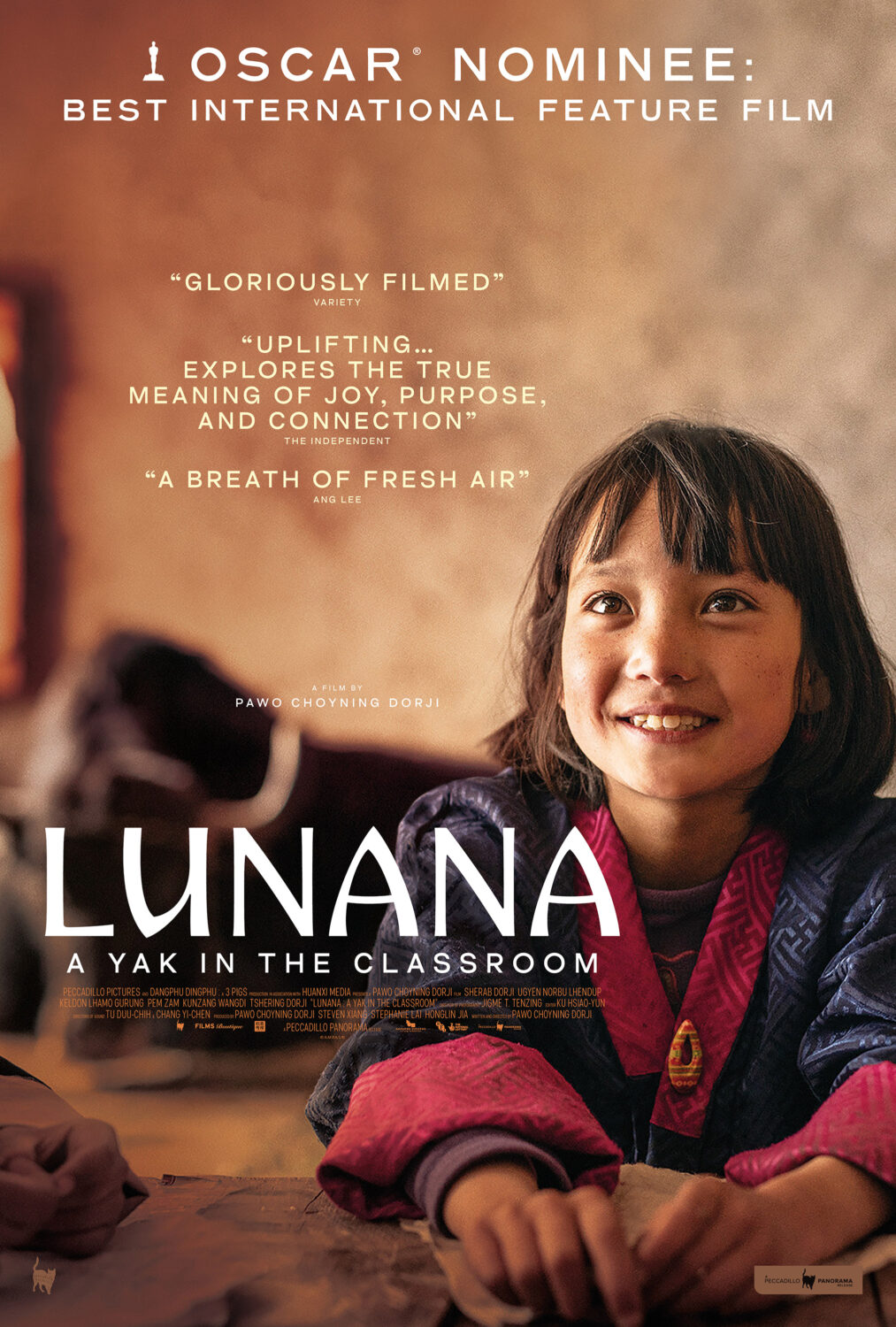

Interview: Director Pawo Choyning Dorji On Making Bhutan’s First-Ever Oscar Nominated Film

By Something CuratedBhutanese director and writer Pawo Choyning Dorji’s Oscar nominated debut feature, Lunana: A Yak in the Classroom, is set for its UK release on 10 March 2023. When Ugyen, a day-dreaming and dissatisfied young teacher, is posted to a school in the remote village of Lunana, dizzyingly high up in the Himalayan glaciers, he is disheartened to find a simple yak herding community lacking basic amenities such as electricity or even a blackboard. But the enthusiasm of his young students and the unassuming warmth of the village folk buoy Ugyen’s spirits and he must decide whether to return to the city before the gruelling winter sets in or remain in this challenging and charming land. Beautifully photographed in extraordinary locations, this poetic and enchanting drama earned Bhutan the country’s first ever Academy Awards recognition and gives a fascinating insight into a region largely uncharted on screen. To learn more, Something Curated spoke with the film’s creator.

Something Curated: Can you tell us about your background and journey to directing and writing films?

Pawo Choyning Dorji: I come from Bhutan and when it comes to filmmaking, I think this is a very accidental profession [laughs]. I never went to film school. This is my first film. I worked on other films as the directors’ assistant; I helped produce a film before. But this is my first time actually doing it. For me, I’ve always been drawn to storytelling. In my country, storytelling is such an important part of our culture and tradition, so important that it does not even have a word for it. In English, I would be like, “Please tell me a story.” In my language it would be, “Please untie a knot for me.” So the act of telling a story is supposed to have this purpose of untying, freeing, liberating. I suppose that’s what drew me to telling stories. I used to write a lot. I used to be a photographer. And then I got into filmmaking because I thought it was the most powerful medium to put across stories, to untie knots. When I made Lunana: A Yak in the Classroom, it was a very small film project. I feel as filmmakers, we have a very important responsibility to preserve within our stories – we are almost like the scribes of our time – so the film was really made because I wanted to preserve within it what Bhutan was going through. I wanted to show the story of Bhutan in this day and age. Really that was it – I never expected it to go and travel where it has.

SC: Can you talk more about what inspired you to make Lunana: A Yak in the Classroom?

PCD: I don’t know how much you know about Bhutan – we’re known as “the happy country.” Wherever I go, the first question is always, “Where are you from?” And when I say, “I’m from Bhutan,” I can almost guarantee the reaction will be, “Oh, you must be very happy then.” What a lot of people don’t realise is that Bhutan, beneath that veil of happiness and Shangri-La, we have really pressing issues. We are a third world country where unemployment is high; so many of our youth are leaving our country for countries like Australia. Younger generations are forgetting about our culture and our traditions. I wanted to create this story where the protagonist was representing the current state of the country – that is, leaving Bhutan, ironically, to seek happiness elsewhere. Currently, that elsewhere is Australia – a place that represents the glittering lights of the modern world. I wanted to create a story in which the protagonist is pushed unwillingly into the very opposite, that was Lunana – the most remote and desolate place. Lunana, in our language, because it’s so remote, translates to “the dark valley.” So really, the film asks, can we discover in the darkness of shadows what we are seeking in the light? As we receive with the story of Ugyen, as he travels to Australia at the end, it really is that only through the experience of the shadows and darkness, that we can truly appreciate what light is.

SC: There are a number of parallels between the characters and actors playing them, including Sherab Dorji and Pem Zam – could you tell us about your process of writing in regards to how the story adapted around the cast?

PCD: This film is almost like a docu-feature. This approach came about for different reasons. One is because I get inspiration from the people I meet and the conversations I have. But perhaps more importantly, in Bhutan we have no professional actors and for me to be able to get the best out of my actors, I make them do as little acting as possible [laughs]. So for example, when I met Sherab Dorji, I had this character in the movie and he was a teacher who was an avid musician and he really wanted to sing, and he wanted to leave his career in Bhutan to go and sing. As mentioned, since there are no professional actors in Bhutan, through word of mouth, I started looking and I met Sherab who had never acted before. When we spoke for the first time, I really felt he represented who Ugyen was. He was confident, he spoke well, he had a good screen presence, he was able to sing and so finally, I asked him, “What are your plans for the next six months?” And he said, “Oh, I’m waiting for my Australian visa because my parents have already moved there.” And I said, “Just hold on for a while, I think you’re perfect for this film.” So we cast him.

And then when we went up to Lunana, I met people up there and it was even more of a challenge. The people from Lunana had never been out of Lunana. So at least for Sherab, he had references; I could be like, “Watch this movie, Not One Less by Zhang Yimou,” for example, to give him some context about what I’m trying to do. But with people in Lunana, forget about a movie, they don’t even have light bulbs. So for people like Pem Zam, or the Village Head Man, I would meet them, hear their stories, and then I adapted the script to fit them. So when they are on screen, their only instruction is, “Tell us your story.” For example, when I first met Pem Zam, I discovered that she doesn’t have her mother, her father was so drunk that he couldn’t even get out of bed to talk to me – I had to talk to her really elderly grandmother to get permission to cast her. Her life up there inspired me to adapt the script so that it’s more authentically her. Not only that, but in the classroom scenes, we just placed the camera there and let the class go on. So in a lot of the scenes where the teacher is teaching the students, and the children are copying from one another, digging their noses – these are all very authentic moments. We didn’t ask them to act – they were just being themselves.

SC: How was your experience filming on location in Lunana?

PCD: It was very difficult. My crew and I, we pride ourselves, coming from Bhutan, as being mountain men, rough and tough [laughs]. But when we got to Lunana, it was totally different. Two weeks into the shoot, we lost our production designer because he got really bad altitude sickness. Imagine living in a place that’s 5000 metres above sea level; you’re above the tree line. There’s no network; you can’t message your loved ones; there’s no electricity; even a shower is such a luxury. To cook our food, we’d carry firewood from below the tree line and bring it up. So there were daily challenges. Because there was no electricity, we had solar panels installed to charge all our cameras, sound equipment and computers. We had basically no lighting equipment and shot nearly everything with natural light. At the end, when we finished the film, I was telling the group that even if the film doesn’t do well and doesn’t go anywhere, we can take pride in the fact that we shot a film that was carbon negative [laughs].

SC: How did you feel about being nominated for the Best International Feature Film at the 94th Academy Awards?

PCD: It was very surreal. I didn’t know how difficult it was to get a nomination – forget about nominated, even shortlisted. As I said earlier, for me, I made this film without any motivation. It was just about capturing what Bhutan really was. After the film was made, this whole idea of submitting to the Oscars came about. And when I started to explore that idea, I realised that Bhutan wasn’t even mentioned in the Academy page. Even our language wasn’t included in the menu. So I actually submitted the film more as a way of creating a space for Bhutan. Bhutan is tiny – oftentimes it feels like we’re so insignificant in the world. And sometimes staking a claim for cultural sovereignty or linguistic standing can be done outside the sphere of politics, through art and creativity. This is exactly what I wanted to do. I took so much pride in forcing the Academy to update their entire website to accommodate Lunana: A Yak in the Classroom – they had to add Bhutan, to add Dzongkha in their language section. For me, that was a big achievement.

SC: Are you able to talk about any upcoming projects?

PCD: I’m currently in postproduction for my second film, which is called Four Days to Full Moon. It’s another story about the change and transition of Bhutan. I would say this is more of a comedic story. Bhutan was the last country in the world to allow television; we were the last country in the world to allow Internet. And the film is really about the social changes and implications that these technologies coming in so late have had. When TVs first came in, societies changed so drastically. Like, the person who had the largest TV would become the most popular person in the village. People started selling their yaks in order to buy televisions. And when the TVs came, they would put them in the shrines with the Buddha statues and make offerings to the TVs. So this society that had for so long had Buddha paintings hung on the wall suddenly started replacing these with WWE and David Beckham posters.

Feature image: Lunana: A Yak in the Classroom