Interview: Lina Iris Viktor On The Libyan Sibyl & Beauty As A Tool For Truth

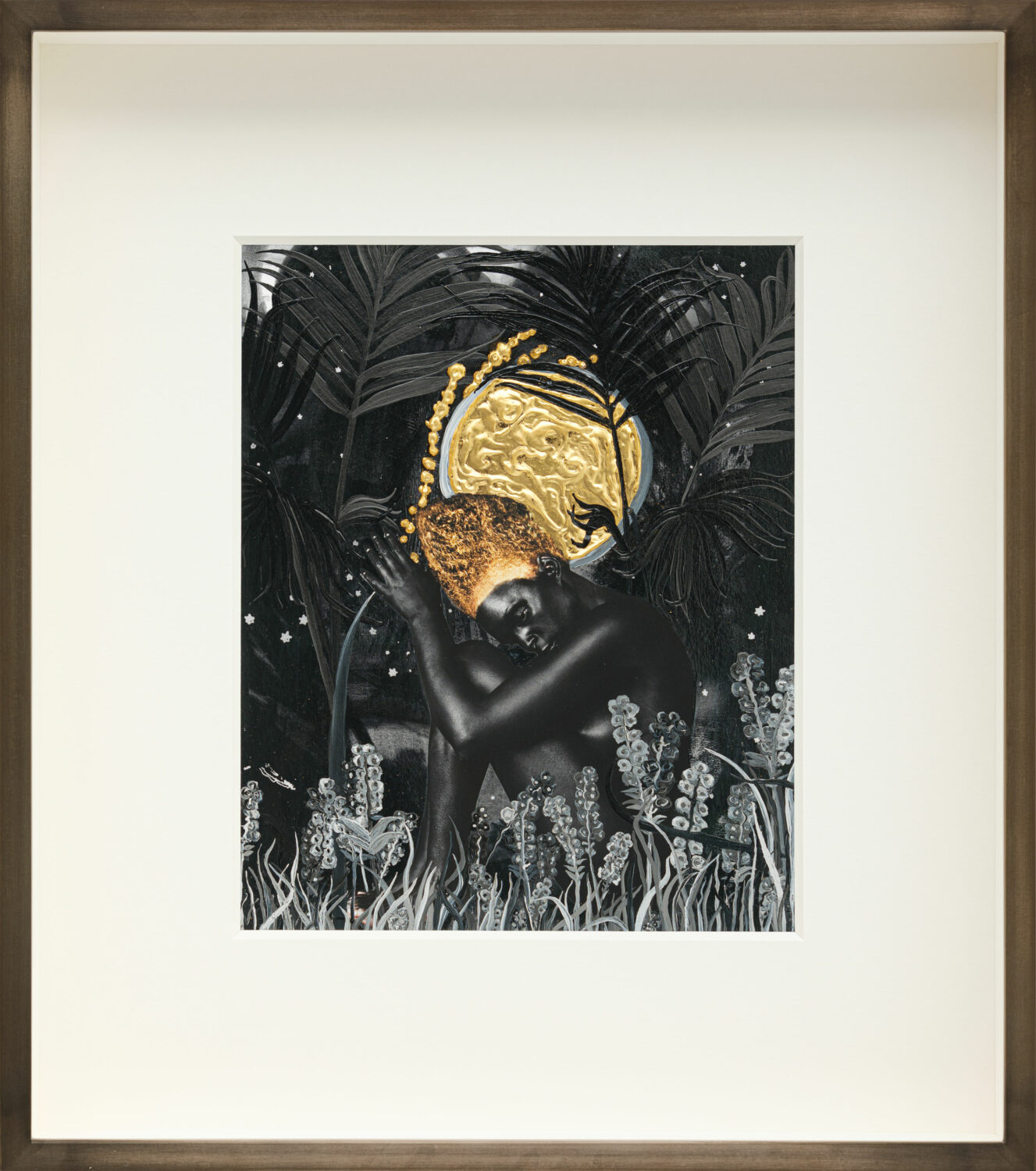

By Something CuratedLina Iris Viktor is a British Liberian multidisciplinary artist who works between Italy and the UK. Her work weaves together performance, photography, painting, water-gilding and sculpture to create rich, lavish works featuring mythical and majestic looking female figures. Through these sensuous and visually loaded works, pattern becomes a ‘pre-verbal language connecting to that which is already encoded within us’ and beauty conveys truths that both comment on and transcend the socio-political. Her work resides in collections all over the US, notably in the National Museum of African Art, Washington, DC and North Carolina Museum of Art, and she has had exhibitions at Somerset House and the Hayward Gallery, London, amongst many others. Her powerful series A Haven, A Hell, A Dream Deferred was recently shown to great acclaim in the touring exhibition In the Black Fantastic, curated by Ekow Eshun, and works from her equally profound series The Dark Continent were shown in Pilar Corrias Gallery’s recent show, Let the Sunshine In. Here, Viktor spoke to Something Curated about the performative aspects of her work, her art-making process, the power of blackness and the mystical figure of the Libyan Sibyl.

Something Curated: You incorporate precious materials (such as pure 24-carat gold) and bold colours in your portraits and place your mythic figures in regal positions. Is there a performative element to your works and is this informed by your previous education in film and the performing arts?

Lina Iris Viktor: I’ve always said my works are performative. People like to refer to my work as self-portraiture, because I use myself in my work, but my response is ‘the work is not reflexive in any way’. When I used to do pure photography I worked with other models, but in terms of conceiving what I like to create, it’s easier to use myself. There’s something so intimate about you, the camera and lights at that initial stage. It allows you to push yourself out of your comfort zone and take more risks. For every image you see – and this is true of all photographers and artists that use photography as a base for their works – there are about 500 that were scrapped. When I get in front of the camera, I can be whoever I want to be; I start to think about what it is I want to express and then I become that character. So it’s never about myself; it’s about a representation of something more grandiose than myself.

When your work involves ideas about the Libyan Sibyl, Greek gods and prophetesses, towering figures in time and history, it allows for a certain kind of freedom, even when you project your own worldview onto them. There is no clear depiction of how these figures look or must be owing to their mythos. Visualising and personifying mythical figures makes it, therefore, a kind of performance, because it’s not about myself. In those moments, when I inhabit these figures and the image is being captured, there is a performance. It’s live for me, but not for the prospective viewers – they are left with the ashes of that performance and all that is imposed on top of it: the intricate gilding, painting, creating layer-upon-layer. But the original image remains the performative essence of the work. Performance is my first love and to impart that into painting, into visual arts generally, is something that’s not commonplace. To still retain that in the work without being a live performer, is rare.

SC: Of course performance can be a kind of ritual, which chimes with your use of myth. Would you say there is a kind of ritualistic process at play in the making of these works?

LIV: There is this sense of doing something so much larger than you. When I start to see the physical thing take form it feels like I didn’t make it. I’ve always had this sensation, even though I know how physically laborious it is to make these works at every stage. From photography and using my own body – because I work facing downwards (I’m always crouched over the work and it’s very physically taxing) – to the use of textiles and the surface textures done by hand. That being said, the end of the process – when you’re doing something repetitive and the composition is there, you’re just painting, filling it in and adding the gold – can almost be a point of zoning out. I love that stage. The hard work is done at the beginning where I’m making all these considerations about the composition, the figure, and how best to represent them. The latter stage is very zen, as I’m working on what has already been decided. There will always still be elements of the unknown in that process, but I’ve already made the important decisions. By the end I have a sensation of separation from it: did I make it or didn’t I make it? I know I’ve made it, but there’s distance.

SC: Does the decorative have political significance for you? Or are you using adornment and embellishment to transcend such contexts and positionalities?

LIV: There are people in the art world who are collecting and changing their viewpoints on what they’ve been told is ‘serious art’. I’ve always believed that beauty is a tool and a way to capture people’s imagination and attention very quickly. Then you reveal other things through it. The reality is, as human beings, we are drawn to beauty, whether it’s in the form of other people or things. Beauty is different to different people, but there’s a universality to the idea that something is inherently visually appealing. I’ve never shied away from that. To an extent it was fortuitous that I didn’t go to art school, because I didn’t have to unlearn that it’s not acceptable to do certain things. I did what felt intuitive to me. I’ve had people tell me my work is decorative and that has negative connotations in certain contemporary art spaces; however, I don’t perceive it as such – just like using black is not negative.

I always look at the pattern systems that surround us and consider how to visually express them, because they’re so dense. I want to synthesise and put them into visual form. I don’t have a deep feeling about the decorative aspect. If people want to read that it’s a good or bad thing, that’s their opinion, but for me I see the world this way: I see both the complexity and simplicity of things. When I’m making work, even though it’s very dense with a lot of information and patterns and symbols, holistically there’s still an order to it. There’s chaos in the order and order in the chaos, which is really important to me. It’s never about how much I can add or how decorative this work can be. Rather, it’s about what is the perfect balance between density and surface tactility and flat areas. How do you play with and create a visually loaded image, but not so loaded that it knocks you out and you can’t compute or engage with it? With The Dark Continent series (2015-2023), which is made up of different blacks and greys, I treat the work with varnish so that even though there can be one kind of black across the entire background you see different parts come in and out, adding a three-dimensional visuality to the work. The same could be said of the gilding. It’s about how to play with the fields of the eye through the work. I let people put their labels on it, but I don’t think in those terms at all.

SC: Would it be true to say The Dark Continent series exudes the power of blackness because of those layers of paint? It’s sumptuous, but pulsates with so many meanings and connotations and feelings.

LIV: It’s primal, because when I discuss black, especially in this very charged socio-political climate, all the conversations around blackness are about how it pertains to race. I’ve always maintained that my conversation is not purely about race. I think that’s reductive in many ways. There are many other facets we can speak about when it comes to colour, beyond this socio-political conversation. The way I talk about black is as the materia prima – first matter. It’s what we see when we look up into the night sky at the universe around us – though whether it is truly black is another thing, but that is how we perceive it. As is the case with gold, we have such a storied history with blackness and the fear it connotes, and this in many ways has been transposed onto the conversations we are having about race. Yet it’s a larger conversation; it’s about how we as people relate to darker things in general, and how it siphons down into the socio-political milieu. I don’t look at black as a colour, I look at it as a value. It’s a potent, mystical, magical kind of hue. It sucks in and holds information; it doesn’t reflect; it contains almost everything. Then there’s the contrarian in me who didn’t go to art school, but at the same time is versed in the teachings of art schools and how they’ve taught people to stay away from the denser, darker colours in their works, because of how it sucks in light. So there’s part of me that’s like, ‘ok, I’m going to do exactly that’.

SC: Ekow Eshun has described the figure in your profound and stunning series A Haven. A Hell. A Dream Deferred (2017-18) as a merging of the divine prophetess from Greek Myth with the abolitionist and women’s rights activist Sojourner Truth. You’ve already mentioned her, but could you talk more about this figure, the Libyan Sibyl, and her importance in your work?

LIV: I was asked in 2018 to do a show in New Orleans during the city’s tri-centennial. The whole series, A Haven. A Hell. A Dream Deferred, which features the Libyan Sibyl, came from that solo exhibition in New Orleans Museum of Art. There are many states in the US that have storied histories concerning Liberia and slavery. I knew less about the relationship New Orleans had with Liberia, but as a Liberian artist I wanted to know how it fit into New Orleanian history as well as wider US history. Initially I was told there wasn’t much of a tie between the two places, but then I started digging in Tulane University and discovered John McDonogh, an important figure in New Orleanian history who is still very present in terms of statues, schools and districts being named after him. McDonogh has been referred to as a slave owner with a “heart of gold” because he allowed his slaves to work for their freedom before abolition occurred.

He was also one of the members of the American Colonization Society (ACS), who placed freed slaves in Liberia. This is all part of New Orleanian history, which still hasn’t properly been delved into. Discovering this catapulted me into thinking how I should tell this story, specifically to New Orleans and also the American South, but also the conversation about the founding of Liberia. And who would be the best figure to impose onto this history – and the literal primary source material of maps and historical images that I had amassed and wanted to pour into the work. The source material consisted of people who had moved to Liberia through McDonough via the circuit of the ACS and were writing back to him about their first experiences on the African continent and the newly formed Liberia. When I came across the Libyan Sibyl, who is the prophetess of ill-fated futures in Greek mythology, I thought this is the best translator to tell these stories.

Ironically, during the campaign to abolish slavery, a lot of the writers in the northern states exhumed the figure of the Libyan Sybil to tell the story of the ill-fated futures of the African people who would be taken to the Americas and Europe and placed in servitude. So a lot of abolitionists used the figure, likening her to Sojourner Truth who speaks about how to free yourself from these chains. That’s how the Libyan Sibyl came about. If you go to the MET and see images of the Libyan Sibyl, her posture is that of being forlorn, sitting with her head cupped in her hand and looking depressed because she’s foretelling future doom. Just by her mere presence, I was able to use this figure as a interlocutor of these stories.

Interview by Hannah Hutchings-Georgiou | Feature image: Lina Iris Viktor, Red/ Cazimi, 2021-22. Courtesy the artist and Pilar Corrias, London