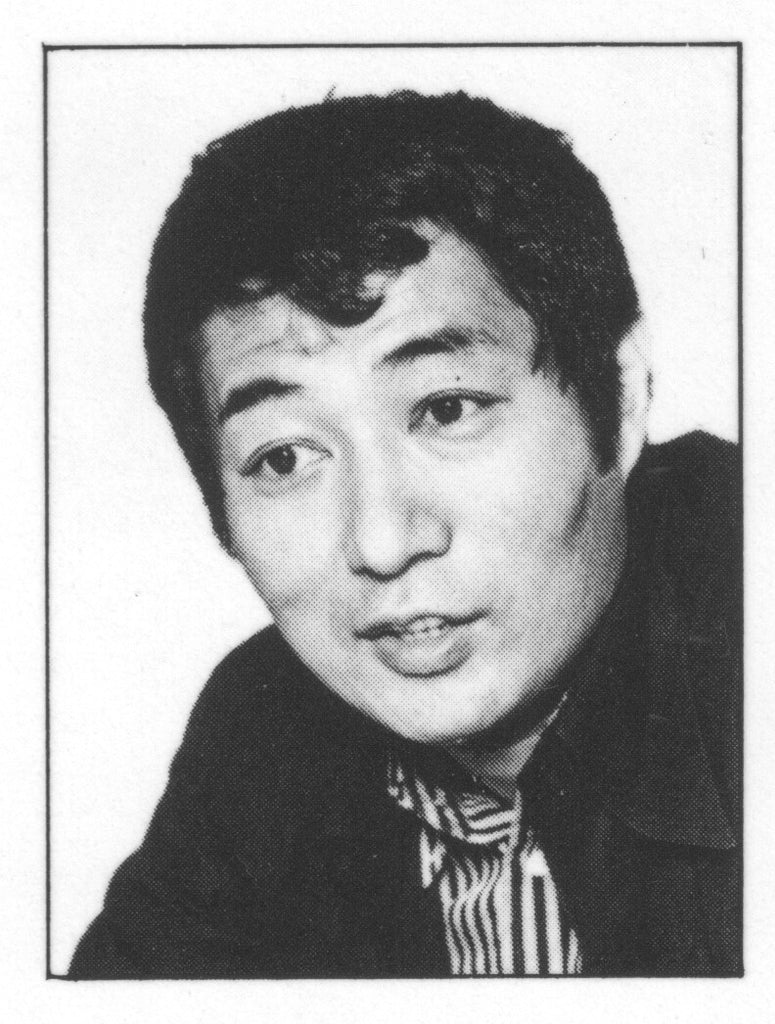

Who Is Shūji Terayama?

By Something CuratedBorn in 1935 in the Japanese city of Hirosaki, a highly influential figure in the post World War II Japanese avant-garde, Shūji Terayama is a bonafide multi-hyphenate. A versatile and prolific artist who earned notoriety in various fields, including poetry, theatre, writing, photography and filmmaking, Terayama was a true cultural innovator. During his short but remarkably productive career, Terayama unrelentingly blurred the boundaries between high and low art forms, broaching different mediums with unfettered imagination. His fusion of theatre, film, and photography was instrumental in shaping his visionary artistic style, leaving an indelible mark on Japan’s cinematic and cultural landscapes. From his early and often controversial involvement with traditional tanka poetry during his youth, Terayama remained steadfast in his belief that true artistic creativity stemmed from breaking existing standards in order to forge new ones.

Since his early days growing up in the Aomori Prefecture, Terayama had an attraction to cinema, nurtured by the time he spent in his uncle’s movie theatre during his childhood. One film in particular, Michael Curtiz’s Casablanca, held a longstanding allure for him and became a significant influence, subtly referenced in his poetry and filmic creations. Not unlike Jean Cocteau, Terayama appropriated and reinvented elements from Casablanca in his own artistic practice. The premature loss of his father also had a profound impact on Terayama’s films, art, and writing, imbuing them with a lingering sense of an absent or enigmatic figure of authority. Terayama’s exploration of masculine influence and the role of the paternal figure, a recurring theme in his art, was particularly pronounced in his films; his cinematic works became a fertile ground for this often-subversive enquiry.

One of Terayama’s best-known films is Emperor Tomato Ketchup, a captivating and surreal journey that delves into the extraordinary escapades of a young monarch navigating his chaotic realm. Set in an indeterminate future in which children have overthrown adults and established their own empire, the film does not have a central narrative or identifiable character roles. Rather it depicts a series of graphic tableaux in which children engage in cruel and abusive acts against the adults under their dominion. These include scenes of child soldiers arresting, enslaving, executing, and assaulting helpless victims, often held at gunpoint. The film exemplifies the boundary-pushing performances that are central to both Terayama’s cinema and his role as the founder of the audacious Tenjō Sajiki theatre group.

Tenjō Sajiki was an independent theatre ensemble co-founded by Terayama, consisting of members including Kohei Ando, Kujō Kyōko, Yutaka Higashi, Tadanori Yokoo, and Fumiko Takagi. Active from 1967 until Terayama’s passing in 1983, the group played a significant role in the Japanese Angura, or underground, theatre movement. Renowned for their experimentalism, incorporation of folklore elements, social provocations, grotesque eroticism, and the flamboyant fantasies characteristic of Terayama’s artistic activity, Tenjō Sajiki produced numerous stage works that left a lasting impact. The ensemble’s visibility greatly benefited from collaborations with eminent artists including musicians J. A. Seazer and Kan Mikami, as well as graphic designers Aquirax Uno and Tadanori Yokoo.

Like Emperor Tomato Ketchup, Tenjō Sajiki’s output embodies Terayama’s persistent call for dissent and even revolution, a resounding theme that echoes throughout all of his films, perhaps most overtly expressed in his play, Throw Away Your Books, Rally in the Streets, which was later adapted into a feature film. In March 2012, Tate Modern in London presented a commemorative event dedicated to honouring the legacy of Terayama. While it is challenging to encapsulate the diverse and intricate dimensions of Terayama’s extraordinary and meandering career, an appreciation of his distinct artistry can be effectively discerned by watching his films, which are now gaining the international recognition they deserve. This is partly due to the dedicated preservation efforts of the National Film Center in Tokyo and the emergence of significant new scholarly research delving into Terayama’s cinema and expansive artistic endeavours.

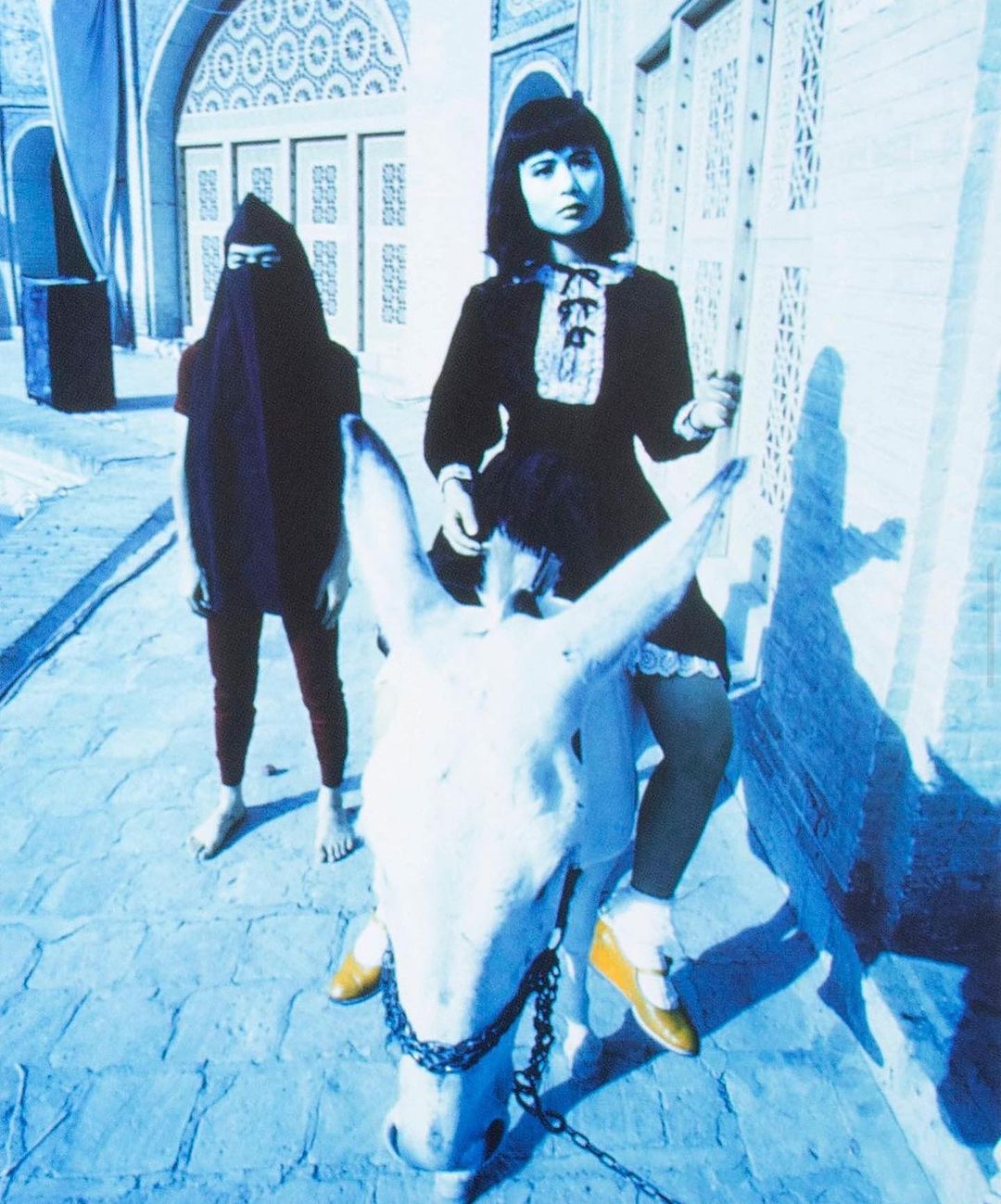

Feature image: Shūji Terayama, Taken from Photothèque Imaginaire de Shūji Terayama: Les Gens de la Famille Chien-Dieu, 1975. Photo: Pinterest