Interview: Meet Shanzhai Lyric, The Artistic Duo Finding Poetry In Bootleg Fashion

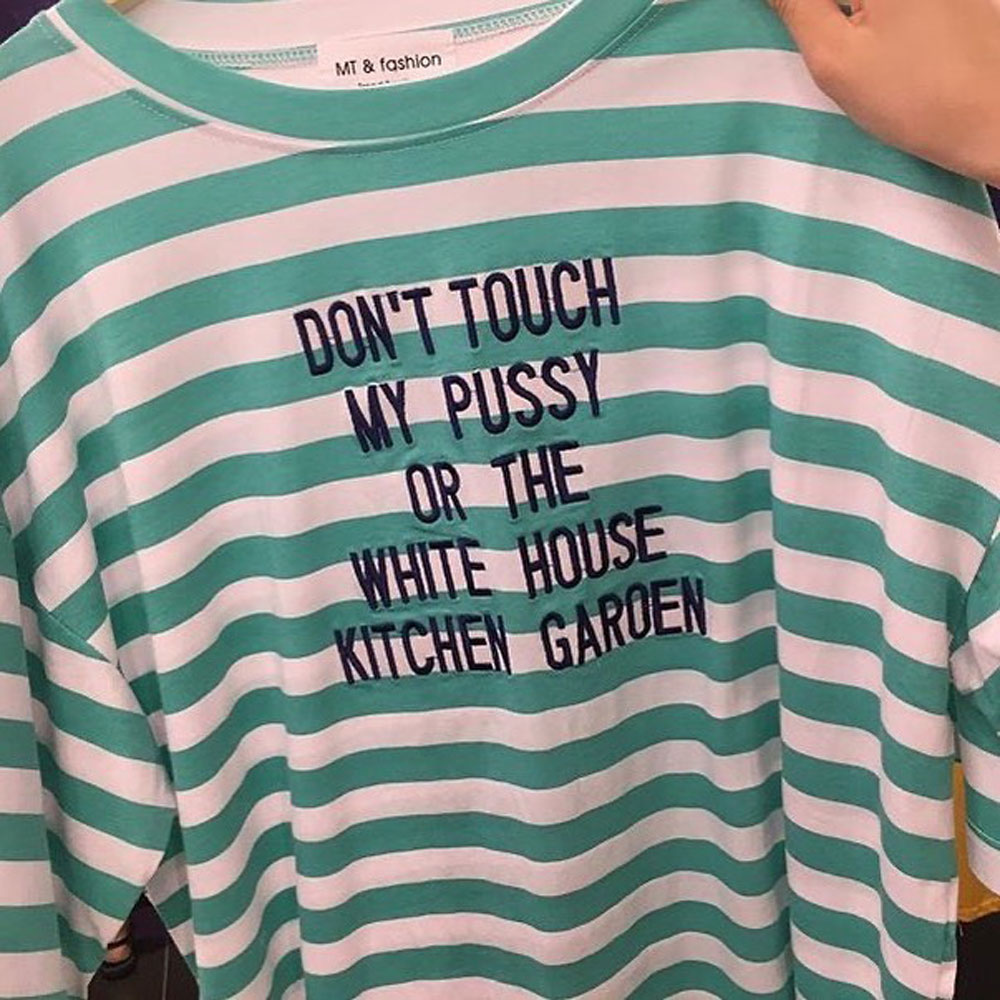

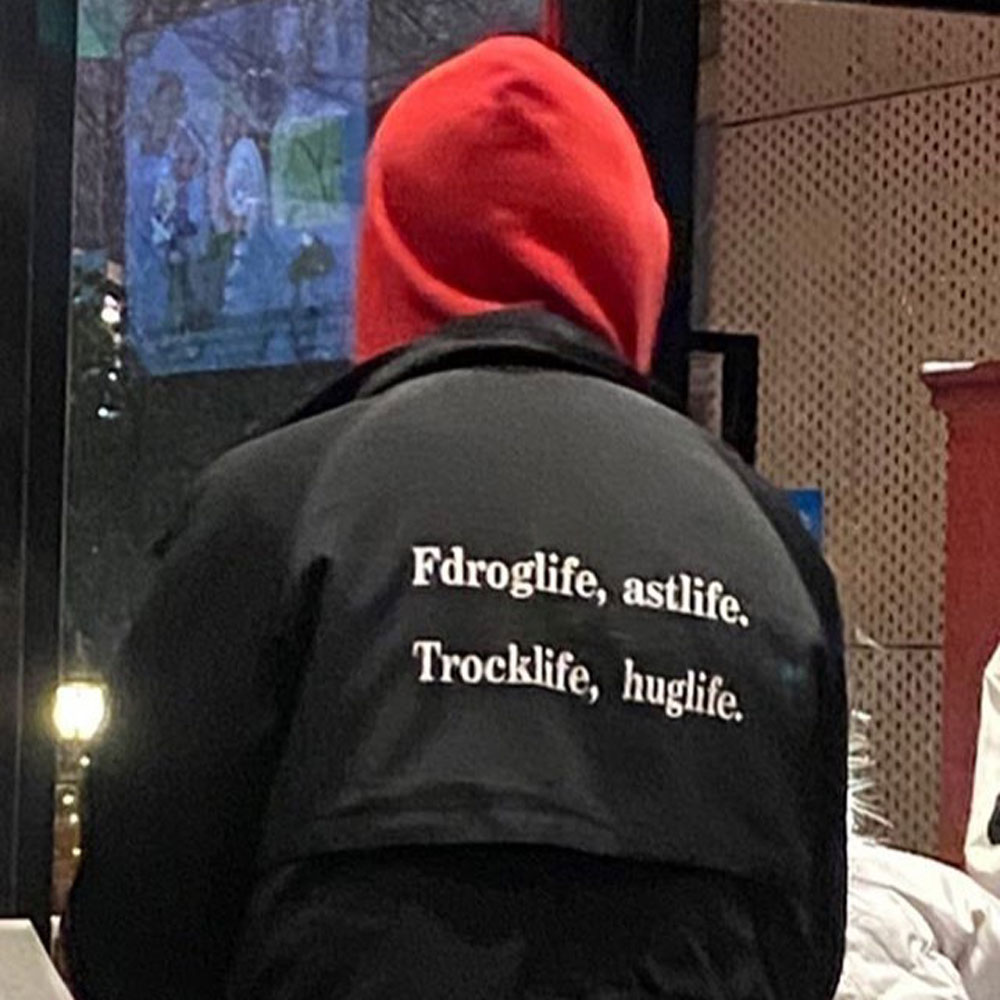

By Something CuratedNew York-based artistic duo Ming Lin and Alexandra Tatarsky are behind Shanzhai Lyric, a collaborative practice that documents and transforms awkwardly translated slogans from mostly Chinese manufactured bootleg garments into an on-going poem. The subversive and unendingly entertaining project has gained a following both in the art world and on Instagram, exploring the global fashion industry and detritus of consumerism, as well as the power of mistranslation as a form of resistance. Shanzhai Lyric will be part of The Weight of Words, a fascinating group exhibition at the Henry Moore Institute, opening on 7 July and running until 26 November 2023, which brings together an international, intergenerational mix of artists and writers, exploring what happens when you combine the flat, linear qualities of poetry with the weight and materiality of sculpture. To learn more about Lin and Tatarsky and the thinking behind their collaborative practice, Something Curated spoke with the creators of Shanzhai Lyric.

Something Curated: Can you tell us a bit about your respective backgrounds and how Shanzhai Lyric was born?

Shanzhai Lyric: At the time this project began, we were researching the ingenuity of adhoc informal markets, as well as the multi-lingual poetics of diaspora – our backgrounds are in architecture and literature. These interests coalesced in 2015 when we went to Beijing to observe and transcribe the poetic nonsense we were finding on garments mostly made in China and worn across the globe, a phenomenon we began calling “shanzhai lyrics.” Shanzhai is the Chinese word for counterfeit and translates literally to mountain hamlet, in reference to an area on the outskirts of empire where bandits stockpile stolen goods for redistribution. The poetics and politics of shanzhai guide our practice, which takes the form of publishing, performance, installation, and a growing archive of poetry-garments we call Incomplete Poem that circulates in libraries, galleries, universities, museums, closets and archives. In addition, we continue to inhabit and consider various “hamlets”—those zones of exception that make possible the sharing of resources.

SC: Do you think about your work as a comment on consumerism?

SL: Shanzhai lyrics are born amidst the churning cycles of production, consumption, and disposal. We are drawn to the quality of this language that emerges amidst the circumstances of fast fashion, and often comments upon the conditions of its own creation. Garbling the names of luxury brands and the verbose declarations of ad copy, shanzhai lyrics imitate but they also mock. The apparent errors are so delightful and intriguing because of this contradiction: they at once revel in and reject consumptive desire. The lyrics often express longing for brands and products whose sanctity they puncture in the same breath.

SC: Could you expand on the power of mistranslation as a form of subversion and, potentially, resistance?

SL: Mistranslation points to the instability and slipperiness of language, the way poetic meaning eludes but can also be created by human-machine collaboration in the form of, say, translation software. What we love about mistranslation as part of the poetic form of shanzhai lyrics is that it pokes fun at the officialness of languages of empire, such as English or French. Delightful errors are a way to reject the norm, to challenge the authority of rules.

SC: What is the thinking behind the work you are presenting at the Henry Moore Institute?

SL: At the Henry Moore Institute, we’re engaging with the history of enclosure as it relates to foundational notions of private property. This iteration of Incomplete Poem is based on the shape of a hedge—an early method of demarcating the boundaries of one’s land, still prevalent in the English landscape today. To help us re-think ideas of theft and ownership, we’re looking to Robin Hood as a disruptive and heroic figure who, along with his merry men, famously stole from the rich to give to the poor. These shanzhai poet-bandits were shielded from the authorities by the hamlet of the Sherwood Forest.

SC: And how do you see Shanzhai Lyric evolving in the future?

SL: We also hope to dig into the other regional histories that propose different ways of thinking about ownership and property. For instance, in 1944, the 28 rebellious weavers of Rochdale established the first workers’ cooperative. Their principles have been replicated all over the world—including at one of New York City’s first cooperative housing complexes: Rochdale Village in Jamaica, Queens. Garment workers are often at the forefront of movements for social justice, fighting for better labour and living conditions, and developing principles of cooperation. Abraham E. Kazan, President of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers Credit Union in America, who led much of the construction of cooperative housing in New York City, famously said that the most effective way to spread an idea is to create an easily replicable model—in other words to proliferate by inciting copies. Bootleg as method continues to inspire us.

Feature image: Shanzhai Lyric, Runway, Tapestry, Heap, 2020. Courtesy the artists and Hesse Flatow