The Story Of Silk

By Something CuratedNumerous myths and legends surround the origins of silk production. According to the writings of Confucius, a tale unfolds around 3000 BCE protagonised by Empress Leizu. It is said that a silkworm’s cocoon accidentally fell into the Empress’ teacup. Curious, the fourteen-year-old girl started unravelling the cocoon’s threads while retrieving it from her beverage. As she unrolled the cocoon, she discovered the long and delicate fibres it comprised. Fascinated by the finding, the Empress decided to weave some of these fibres, collecting a few more cocoons for this purpose. Following the experiment’s success, she observed the life cycle of the silkworms closely. With her newfound knowledge, she began instructing her court in the art of raising silkworms, a practice known as sericulture. In Chinese mythology, the Empress, who stumbled upon the secrets of silk and shared her wisdom with others, was transformed into a goddess.

According to an ancient Indian legend, the beginning of silk can be traced back to the Hindu god Krishna. It is said that Krishna’s wife, Satyabhama, desired to wear a magnificent saree and to fulfil her wish, Krishna himself gifted her a silk garment made from the fibres of a divine tree, which was believed to produce silk magically. In Korean folklore, the origin of silk is linked to a story about a celestial white horse. According to the legend, the heavenly creature descended to Earth and gave a cocoon to a young girl. This cocoon was said to be the source of silk production, and the girl became the first silk weaver in Korea. Vietnamese legend attributes the discovery of silk to a fairy goddess named Âu Cơ, who taught the local people the art of sericulture and silk weaving. And Thai mythology tells the tale of a young girl who discovered silkworms while tending to mulberry trees.

Evidence of silk production can be traced back more than 8500 years ago to the early Neolithic Age tombs of Jiahu, China. Biomolecular evidence reveals the presence of prehistoric silk fibres in these tombs. Excavations also uncovered weaving tools and bone needles, suggesting that the residents of Jiahu likely possessed weaving and sewing skills required for crafting textiles. Further early proof of silk was discovered at sites belonging to the Yangshao culture in Xia County, Shanxi, where a silk cocoon was found cut in half with a sharp knife. Archaeological findings provide confirmation that silk had already gained recognition as a luxury material beyond China long before the Chinese opened the Silk Road, meaning trading was already happening. For instance, silk artefacts have been discovered in the Valley of the Kings in Egypt, with one such find coming from the tomb of a mummy dating back to 1070 BCE.

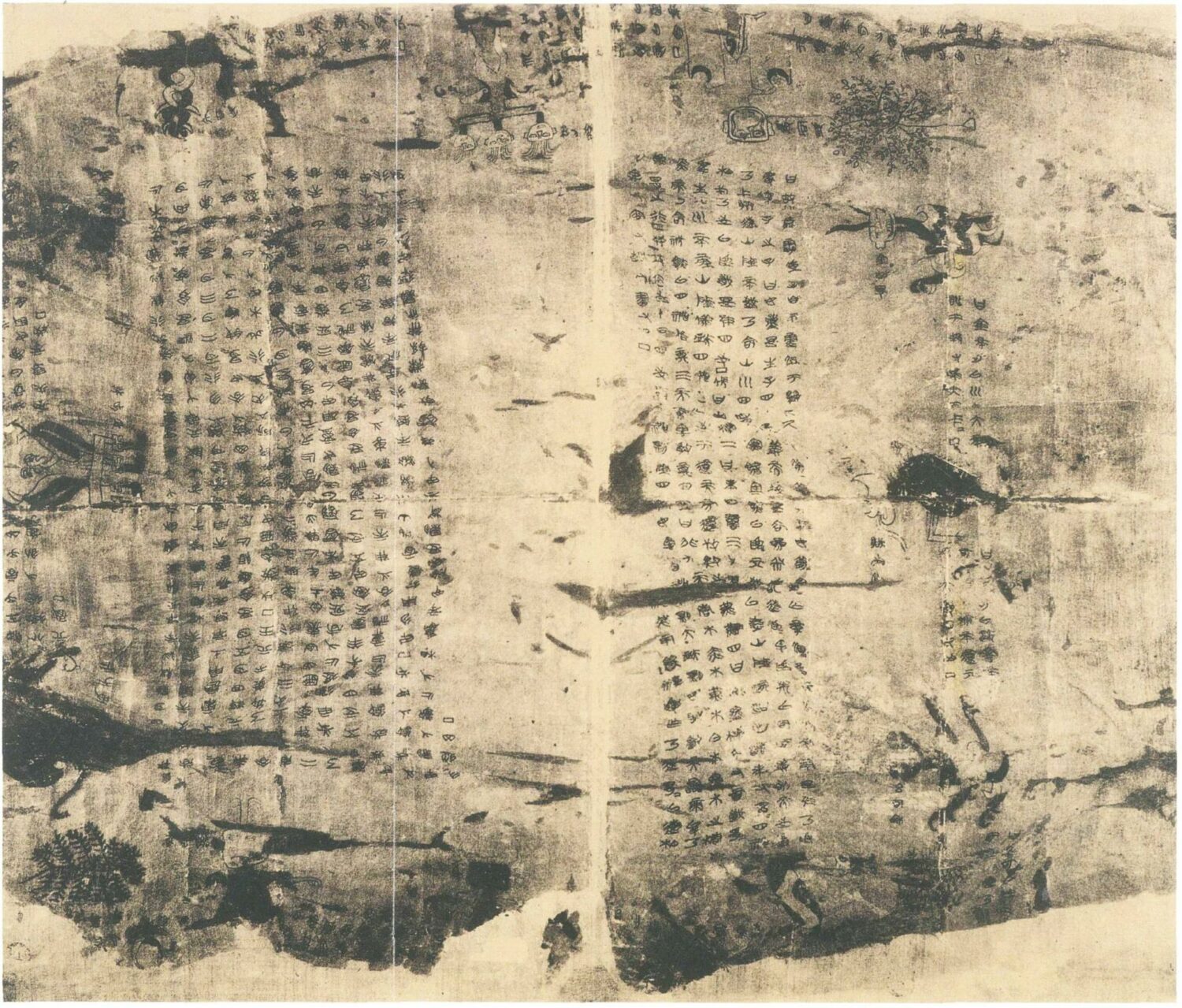

In China, silk was not only used for clothing but also found applications in writing and art. The colour of silk garments carried significant social import and served as an essential indicator of class during the Tang dynasty. While silk was extensively exported, the Chinese zealously guarded the art of sericulture, keeping it a well-protected secret for over a thousand years. As a result, other cultures created their own narratives and legends to explain the origin of this mysterious and highly coveted fabric. Despite eventually spreading to other parts of the world, the Chinese managed to successfully retain exclusive control over silk production until the opening of the Silk Road when silkworm eggs covertly made their way out of the country, supposedly via monks. The earliest known examples of silk production outside of China come from silk threads discovered at the Chanhudaro site in the Indus Valley civilisation.

By 300 CE, Japan had fully embraced silk cultivation, and by 552 CE, the Byzantine Empire had acquired silkworm eggs. Around the same time, the Arabs also started producing silk. The Crusades introduced sericulture to Western Europe, notably in various Italian states, resulting in an economic boom. In the 16th century, France joined Italy in establishing a thriving silk trade, while most other European nations’ attempts to develop their own silk industry remained unsuccessful. During the early 20th century, Japan, undergoing rapid industrialisation, emerged as a major silk producer, accounting for approximately 60 per cent of the world’s output. With economic reforms, today China has once again become the world’s largest silk producer, followed by India. Despite the introduction of numerous new textiles over centuries, the global popularity of silk remains strong, and its demand shows no signs of diminishing soon.

Feature image: Silk glove with cloud pattern from China, Han dynasty, radiocarbon dated 120 BCE – 90 CE. Cotsen Textile Traces Study Collection. Photo: The International Institute for Asian Studies