Art As A Voice For The Natural World

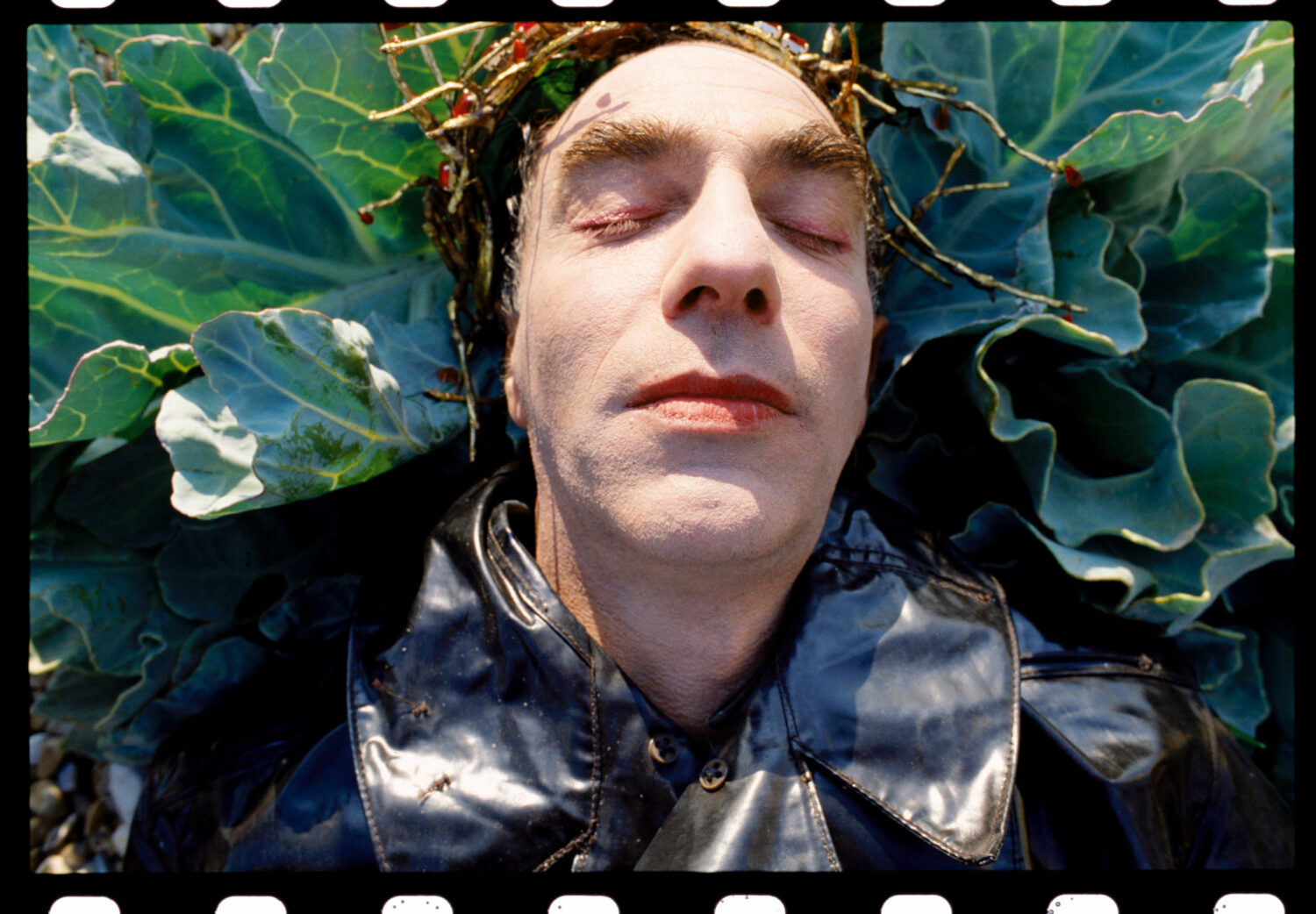

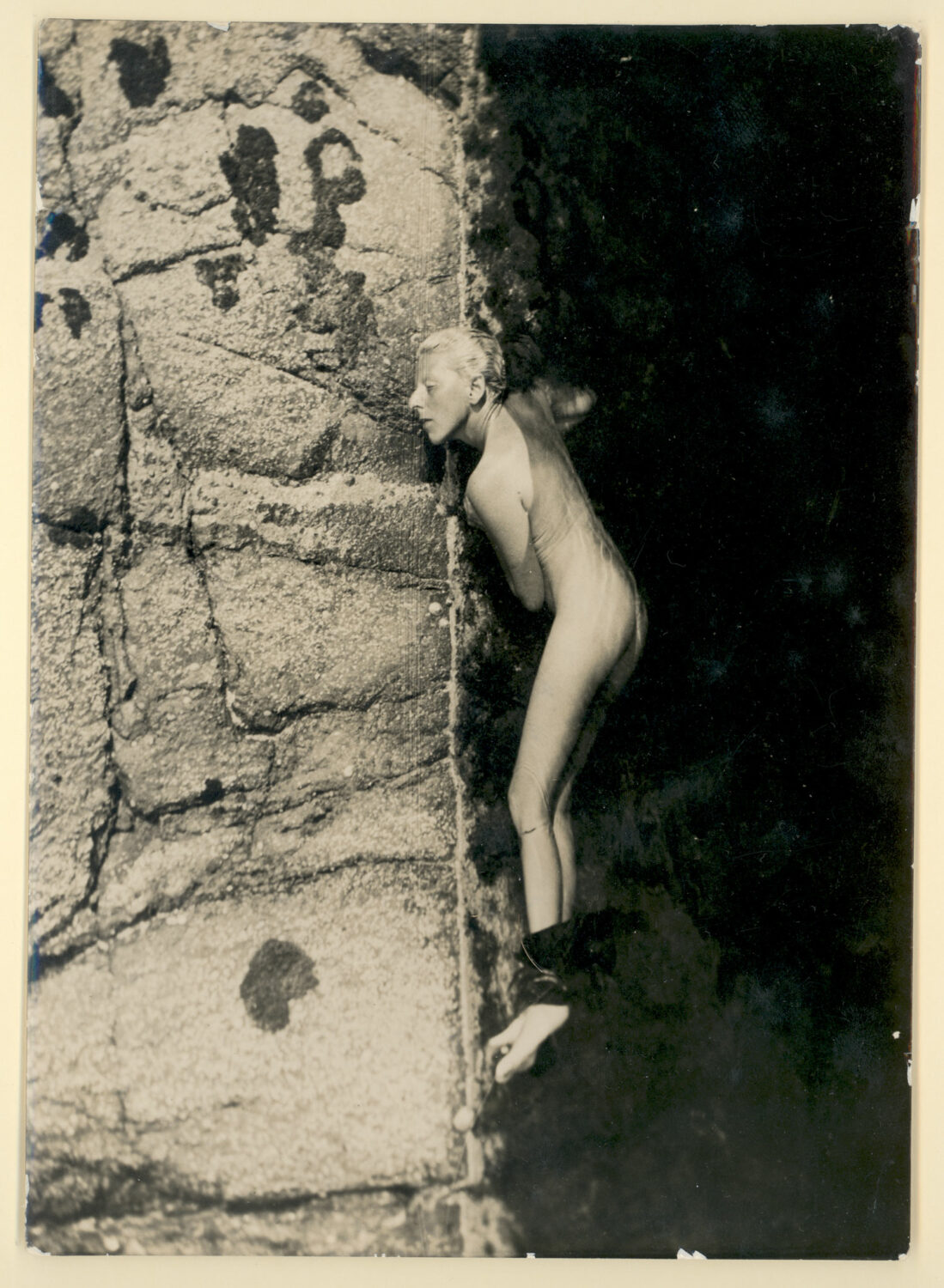

By Something CuratedAristotle articulated, “Art not only imitates nature, but it also completes its deficiencies.” Examining this statement, scholars have posited the Greek philosopher suggests art, transcending the act of replicating, provides fresh perspectives on the natural world while acting as an instrument to amplify nature’s often overlooked voice. Opening on 21 October 2023 and running until 18 February 2024, the William Morris Gallery is set to present Radical Landscapes, an exhibition exploring the natural world as a space for artistic inspiration, social connection, and political and cultural protest through the lens of William Morris, one of Britain’s earliest and most influential environmental thinkers. Organised in collaboration with Tate Liverpool, the exhibition will display work spanning two centuries and feature more than 60 works by artists including JMW Turner, Claude Cahun, Hurvin Anderson, Derek Jarman, Jeremy Deller and Veronica Ryan.

The exhibition contemplates how our landscapes have been interpreted, accessed, and exploited across various social, class and racial divisions. It also endeavours to examine the contemporary global climate crisis, starting from Morris’ own connection to the land. Among the compelling contemporary works on display will be Anthea Hamilton’s British Grasses Kimono (2015), which features enlarged, fragmented images of grasses found in Britain digitally printed onto silk, with snippets of their descriptions trimming the bottom edge of the garment. Made from natural materials including silk, cotton and wicker, the garment blends nature, culture and appreciation. Hamilton has expressed that she employs the kimono as a deliberate compositional tool, serving as a means to unify various distinct elements into one object.

A dedicated segment of the exhibition delves into the act of trespass, explores themes related to geographical identity and a sense of belonging, and scrutinises how communal land rights have been eroded through practices like enclosure, privatisation, and the commercialisation of green spaces. This process, which can be traced as far back as the 17th century, serves as the central theme of Hurvin Anderson’s artwork, Double Grille (2008), which underscores both the physical and symbolic significance of land acquisition in the context of British imperialist expansionism. The exhibition will also feature five sculptures created by Turner Prize winner Veronica Ryan. These sculptures embody her fascination with natural forms like fruits, seeds, and vegetables, and their potential to chronicle narratives of migration, intergenerational exchange, and ingrained memories.

Another important body of work highlighted comes from The Format Photographers Agency. Comprising a group of women dedicated to capturing people and subjects often overlooked in mainstream media, they documented the Greenham Common Women’s Peace camps. These camps were a series of protests and sit-ins that occurred between 1981 and 2000 in response to the British government’s utilisation of the RAF base for the storage of nuclear missiles. By shedding light on the subcultures and communities engaged in protesting the increasingly politicised and militarised treatment of land during the latter half of the 20th century, the exhibition aims to draw connections with more recent climate demonstrations and political conflicts.

The concluding segment of Radical Landscapes makes direct reference to Morris’ utopian novel News from Nowhere, showcasing the extraordinary holdings of the William Morris Gallery. When viewed through a contemporary lens, the similarities between present-day global environmental movements and Morris’ own perspectives on sustainability and his critique of industrial capitalism are still fascinatingly pertinent. Notable works, like his Lea fabric design created as part of a textile series celebrating the splendour of British rivers, exemplify Morris’ dedication to preserving the memories of his childhood haunts, such as the River Lea and Epping Forest. These works also underscore his disapproval of the advancing urbanisation he witnessed encroaching upon precious natural landscapes.

Feature image: Andrew Testa, Allercombe camp on the route of the A30 in Devon, 1996. © Andrew Testa