How ‘The Color Of Pomegranates’ Became Cinema’s Ultimate Moodboard

By Something CuratedArmenian filmmaker and screenwriter Sergei Parajanov’s films stand as some of the most uniquely styled works in the history of cinema, firmly establishing his place among the world’s most influential directors. Born in Tbilisi, Georgia, Parajanov pursued his filmic education from 1945 to 1952 at the Gerasimov Institute of Cinematography in Moscow, under the guidance of esteemed figures like Aleksandr Dovzhenko and Igor Savchenko. Parajanov pioneered a distinctive cinematic approach, one that diverged from the prevailing tenets of socialist realism, the only officially endorsed artistic style in the USSR. This, coupled with his alleged sexuality, led to repeated persecution and imprisonment by Soviet authorities, who also sought to suppress his films. Despite commencing his professional filmmaking career in 1954, Parajanov later renounced all the films he created before 1965, deeming them “garbage.”

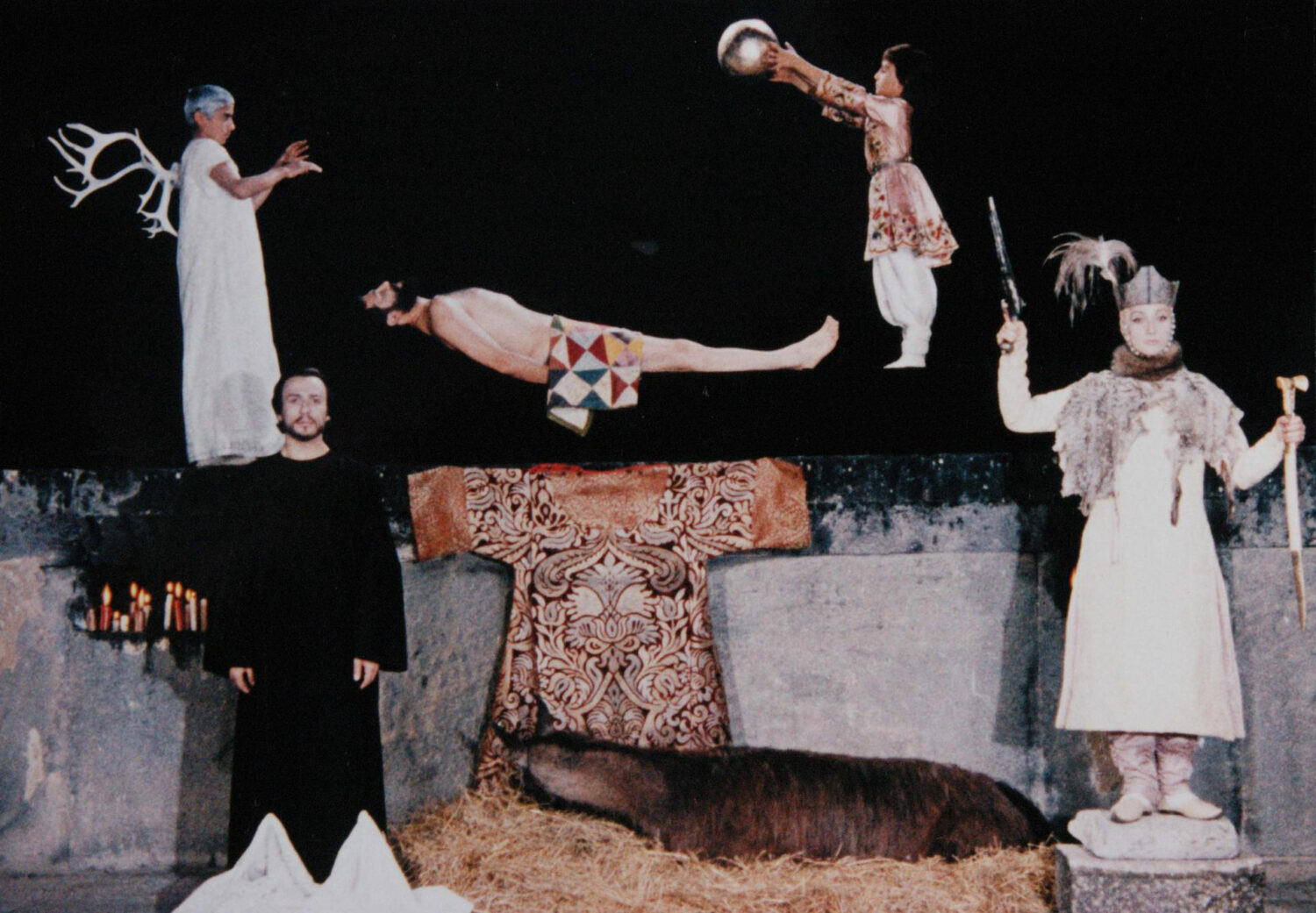

In 1969, Parajanov created what is arguably his most renowned work, The Color of Pomegranates. This visually stunning film transcends traditional storytelling, using a non-linear narrative and a series of tableaux to create a mesmerising tapestry of images, music and symbolism. Each frame is meticulously composed, celebrating Armenian culture and folklore. Eighteenth-century Armenian poet, Arutin Sayadyan, better known as Sayat-Nova, served as the original muse for the film. Sayat-Nova was a troubadour, whose lyrical verses were harmonised with music played on a lute. His distinctive talent lay in his ability to compose in three languages spoken in the South Caucasus region — Armenian, Azerbaijani and Georgian. Consequently, he has been a cherished emblem of unity in the region. Parajanov identified a profound affinity with Sayat-Nova and believed that his own deep-rooted connections to this cultural milieu qualified him to bring the poet’s story to life.

Parajanov’s artistic expression exists within a realm of constant movement and transformation, where reality takes on fluid forms, punctuated by intertwined relationships and moments of varying intensity. The director opted to depart from styles typically associated with biographical works, concentrating on the intricate elements of visuals and sound that conjure feeling. A particular emphasis was placed on capturing the essence of historical sites that held significance in Sayat-Nova’s life, notably the Haghpat Monastery, where the poet spent his later years as a monk. While the film features several rare religious artefacts utilised as props and costumes, Parajanov, credited as the “author” of the project, introduced his creative contributions through various mediums; among these, he designed costumes, including the much-referenced green dress worn by the Angel in the film’s closing scenes.

When it became evident to Goskino, the Armenian film studio behind the project, that the film did not align with their expectations for a biopic, restrictions were quickly imposed on its international screening. The film did not surface in the West until the mid-1970s, through an unauthorised bootleg, coinciding with Parajanov’s imprisonment on charges of homosexuality and dissemination of pornography. This development was the result of advocacy from film scholars who championed the film and voiced their opposition to Parajanov’s incarceration. The director’s unconventional storytelling captivated international audiences and critics alike. While it was perceived as enigmatic and challenging due to its departure from traditional narrative structures, the film garnered a devoted following among cinephiles and scholars who appreciated its poetic qualities.

Since then, The Color of Pomegranates has been referenced and paid homage to in numerous films, television shows and music videos, from American filmmaker Ari Aster’s Midsommar to Madonna’s iconic Bedtime Story visuals, and Lady Gaga’s 911 video. Valentino and Viktor & Rolf have created garments inspired by the film’s sumptuous costuming, among other designers, and Japanese composer Susumi Yokota named a song after the film’s title — to cite a few contemporary examples. Parajanov’s avant-garde approach and non-narrative storytelling paved the way for a greater acceptance of experimental and alternative filmmaking in both independent and mainstream cinema. The Color of Pomegranates remains a subject of academic analysis and critical discourse, continuing to be studied at film schools and art programmes around the world.

Feature image: Sergei Parajanov, The Color of Pomegranates, 1969. Photo: The Criterion Collection