Interview: Roberto Gil de Montes on Huichol Art and the Chicano Movement

By Keshav AnandBorn in Guadalajara, Mexico, Roberto Gil de Montes immigrated to the United States with his family at the age of 13, settling in East Los Angeles shortly before the 1968 Chicano protests for educational equality. A graduate of Otis Art Institute, he became closely associated with the Chicano Movement. Gil de Montes played a pivotal role in a generation of Chicanx and queer artists emerging in the 1970s, exploring diverse artistic genres and identity intersections. While the theme of queerness has been a recurring motif in the artist’s work, it has only recently been recognised as a central element of his paintings.

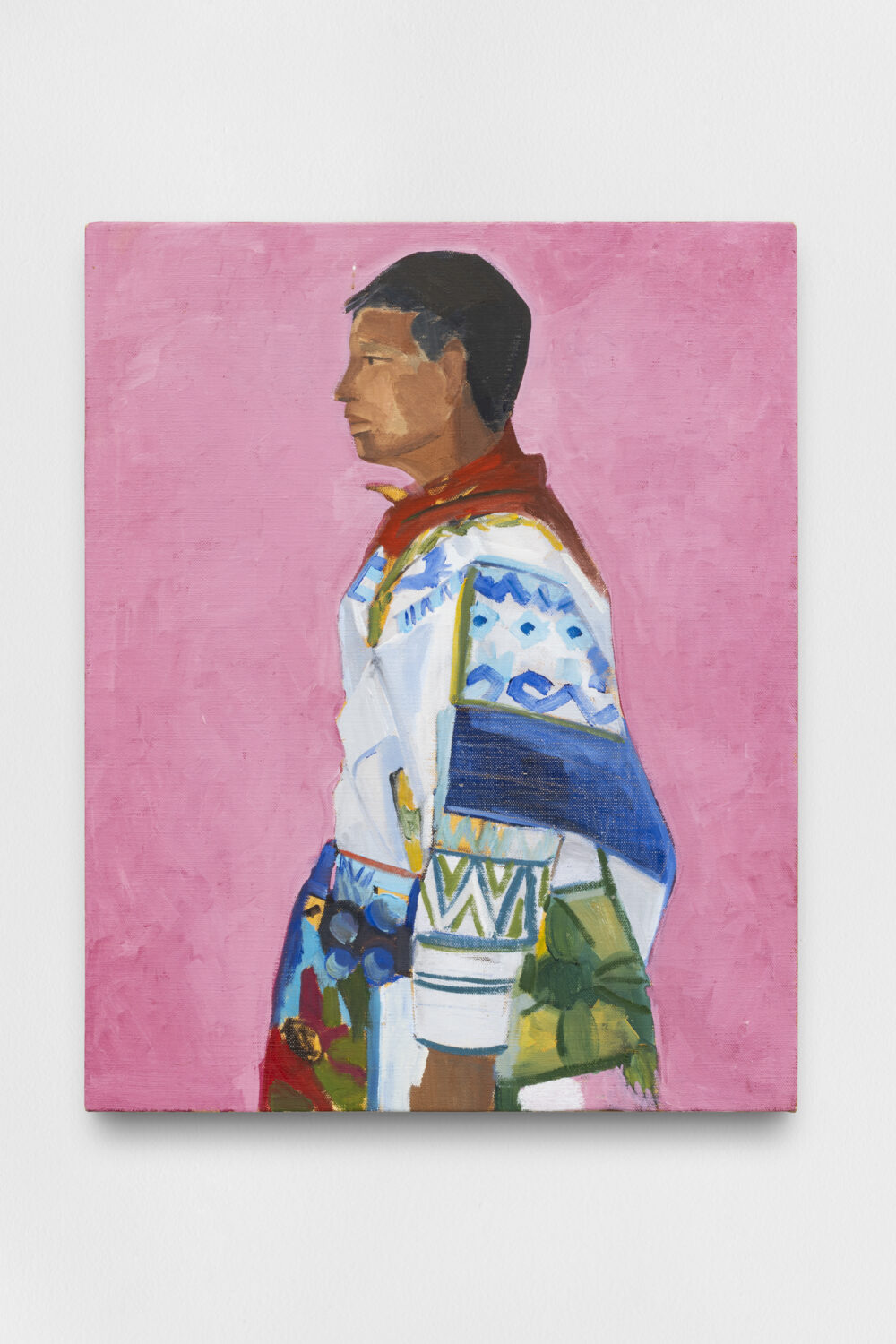

Since relocating to La Peñita de Jaltemba, Nayarit, Mexico in 2006, his art has evolved to portray scenes of tropical opulence and sensuality while questioning notions of mortality and the uncertainties of the present. Open now and running until 22 December 2023, gallery kurimanzutto — conceived by artists Gabriel Orozco, José Kuri and Mónica Manzutto — presents Reverence in Blue, the first New York solo exhibition by Gil de Montes. The show explores themes of belonging and perception, drawing from a rich tapestry of pre-Columbian and Huichol iconography. To learn more about Gil de Montes’ fascinating life and work, Keshav Anand spoke with the artist.

Keshav Anand: Can you tell us about your involvement with the Chicano Movement growing up?

Roberto Gil de Montes: When I migrated to the United States at the age of 13, I was already familiar with the Orozco murals and had attended an elementary school that taught us about our pre-Columbian heritage. In Los Angeles, I began taking art classes in junior high. By the time I was in high school, in 1968, the walkouts started, unfolding across the city. The student walkouts were organised to protest for better educational opportunities and to demand our civil rights. It was through the Chicano Movement that I received the chance to pursue higher education and attend art school.

The Chicano Movement was both a political and cultural phenomenon. Within its cultural dimension, there was an artistic renaissance that encompassed poetry, visual arts, and folk dancing. In visual arts, artists created paintings and murals reminiscent of the work of Mexican muralists. These murals often featured pre-Columbian iconography, the Virgin of Guadalupe, and historical figures from Mexico’s struggle for independence from Spain. Chicanos embraced these images with pride, as if to declare that we were not merely immigrants or labourers, but descendants of a sophisticated culture. This sentiment helped to reinforce the complex identity of Mexicans in the United States.

And I think that’s where I got the idea to use pre-Columbian imagery—something from my culture. Living in the United States, we had this longing to remember and to know where we came from. This sense of pride contributed greatly to the movement because it gave us access to higher education. That’s how I was able to attend art school. After graduating, I returned to live in Mexico City. Coming back as an immigrant and living in such a culturally rich city reconnected me with my heritage and gave me new strength to continue as a painter.

I also met many artists in Mexico City, which expanded my network of friendships to include those from Los Angeles and Mexico, all of whom were artists. This allowed me to see where I fit into the broader artistic landscape. Having a well-rounded education in both American and Mexican art truly helped me a lot.

KA: How has life in La Peñita influenced your work? I’m curious if and how the environment has affected your use of colour.

RGdM: I arrived in La Peñita with my partner Eddie in 1985, and we were immediately drawn to the simple, rustic way of life. It was a fishing village devoid of phone service or television, which we found ideal. It quickly became our getaway destination, and after a few years, we purchased a small ‘casita’ overlooking the ocean and the quaint island in front. During our brief visits, I would paint watercolours, and as our stays extended, I transitioned to oil paints. The local bar, flanked by a brothel, was a melting pot of fishermen, construction workers, gay men, trans individuals, and prostitutes, all mingling harmoniously. This diversity and openness inspired me to return; I admired the authenticity of the people.

We never envisioned living here; it simply happened. The simplicity of life here fuels my inspiration. When I first visited La Peñita in 1985, I encountered the Huichol people. Although I was not interested in the artefacts they sold to tourists, the Huichol yarn paintings I saw in Tepic — the capital of Nayarit — captivated me. However, my interest lies deeper — in the pieces they create for themselves, yarn paintings that narrate the stories of their gods, the harvest, and peyote rituals. Their use of bright colours and lively figures captivated me. At that time, however, I was unable to incorporate this technique into my work in a way that I found satisfying. Eventually, I began to consider adopting the format they used for storytelling, not to convey a story per se, but rather to explore the imagery and its placement within the picture plane.

When I began residing here in 2006, I experimented with pastels in a similar style, but it wasn’t until 2014 that I began painting with a composition akin to theirs, seeking my own symbols. Initially dissatisfied with the results, it was only recently that I managed to harmonise their spatial composition with my painting style. I believe this fusion has allowed me to tap into a spiritual space.

I abandoned the idea but recently in this show, I have one painting that has the format or the way that the Huichol will tell the story, but in my case there’s a human figure in front of it. And I find myself going back and forth, trying to see how I can resolve my interest.

KA: Could you elaborate on your exploration of the human body as a contested space, particularly in the context of queer and trans existence?

RGdM: I often receive questions from observers who note that I predominantly paint men, and it’s true. The body of my work to date largely features male subjects. I don’t believe I’m excluding women intentionally; rather, I paint the male body as a way to explore my own sexuality. I aim to demonstrate that same-sex relationships are not just possible, but that they enrich the world’s cultural diversity, which is beneficial for humanity. I never considered that my work might be seen as ‘queer art.’ To me, it was simply what I felt compelled to paint. Nevertheless, I acknowledge and embrace the significance of continuing to explore this aspect of my identity.

The subjects of my paintings are not deliberately chosen. They emerge from my observations of the world around me. Living in a small town on the Pacific coast, where summers are hot and men often go about in shorts and shirtless, I draw inspiration from these scenes. There’s a certain nostalgia in my work for my younger years, and I have an affinity for the vibrancy of youth, knowing well that this period is ephemeral.

In depicting men within nature, my work carries an additional message: humanity itself should be considered endangered, just like the jungles I paint, which are also at risk of vanishing. In one of my new paintings, featuring three men — two gazing at the viewer and one looking toward the horizon — the horizon itself splits, revealing a breach, an open ocean. I interpret this as a gateway to the future or to another dimension.

I recognise that viewers may have diverse interpretations of my work, and I welcome this. It’s akin to watching a film for the second time — you might notice elements that were missed initially.

KA: What is the thinking behind the selection of paintings included in your current presentation at kurimanzutto?

RGdM: For my current exhibition at the kurimanzutto gallery in New York, it took a year of introspection and practice. I was deeply engaged with the spontaneous ideas that emerged — the ones that popped up in my mind were the ones I felt compelled to paint. This approach presented a challenge: I needed to maintain the integrity of the initial inspiration throughout the entire painting process. There was no overarching theme; instead, I painted daily with a focus on self-observation, like a continuous reflection.

On many occasions, when I felt agitated in the studio, I reminded myself to stay ‘grounded.’ Grounding myself involves stopping my work and sitting quietly in the studio until I feel ready to continue painting. Typically, I’ll pick up a book, which gives me the space to regroup before returning to the canvas. I hadn’t been conscious of choosing the colour blue; it seems that blue chose me, as I wasn’t aware of its prevalence in my paintings until recently. Yet blue is a spiritual colour, laden with meanings, including truth. It’s fitting, as I am constantly in the presence of the blue sky and ocean.

My partner Eddie and I were watching ‘El Dorado,’ a documentary about Berlin’s gay life in the 1920s, and it profoundly resonated with me. The film triggered a flood of memories from my childhood — especially the challenging times of growing up gay in a traditional Mexican Catholic family, where queer identity was unequivocally unacceptable. I internalised the belief that my true self was erroneous, even sinful. Consequently, I distanced myself from Catholicism at the age of 12. Watching this documentary made me reflect on those times because, upon moving to the United States at 13, I discovered a society more accepting of the gay community. I met other young gay people and began to feel more at ease and comfortable with who I was. It opened up new spaces for me, like bars and discos that welcomed the gay community, allowing me to come out and accept myself fully.

A poignant memory resurfaced while watching the film: a young man named Jay from my homeroom class when I was 15. Jay was subjected to relentless mockery and bullying by our classmates — they taunted him with insults like ‘girly,’ and the teacher turned a blind eye to it all. This environment made me realise that, despite feeling a sense of freedom in this country, I needed to conceal my identity to avoid the same ridicule and contempt. The film also reminded me of how Jay, a few years later, embraced her true self and became Anna, whom I encountered again at the age of 22. Another schoolmate from that time, Sylvia, previously known as Manuel, also became a close friend afterward. Initially, I was hesitant to apply a screen over their images in my work, leaving their portraits unobscured for a long time. Eventually, I realised the importance of this element — the screen symbolises the barriers to our understanding that diversity is not only natural but beneficial for humanity.

KA: And what are you currently reading?

RGdM: The Seekers by Daniel Boorstin, and Degas by Theodore Reff.

Feature image: Roberto Gil de Montes, Wrecked, 2023. Image courtesy of the artist and kurimanzutto, Mexico City / New York