Jatinder Singh Durhailay Reimagines Indian Miniature Painting for Modern Times

By Keshav AnandBritish artist Jatinder Singh Durhailay’s mesmerising works re-envision Indian miniature painting, in particular drawing reference from paintings produced during the Mughal Empire. This prolific period saw a convergence of industrial development, urban expansion, scientific progress, and the flourishing of both artistic and literary endeavours — however, with all the advancements, it was not exempt from challenges posed by religious and political unrest. Not unlike the paintings of that era, observing the meticulous attention to detail in Singh Durhailay’s work is most often the initial reaction of the viewer.

The artist works using a brush sourced from Rajasthan; due to the small size of the brush, each piece demands a considerable investment of time, with the painting process frequently extending over months. It is precisely this gradual and meditative practice that the artist relishes. Another nod to the historical works that inspire him, several of his pieces incorporate natural stone pigments and precious materials such as gold leaf. Open now and running until 16 December 2023, The Artist Room in London presents Free Flowing Forms, a solo exhibition by Singh Durhailay. To learn more, Keshav Anand spoke with the artist.

Keshav Anand: Could you give us some insight into your background and journey to artmaking?

Jatinder Singh Durhailay: Born in Britain in 1988, I spent an influential part of my childhood hearing devotional tales, “Sakhia,” from my grandmother, who would visit us from her native country, India, nearly every year. I was never far away from the root of South Asian culture and teachings, although I lived in east London. I regularly received beautiful books about the Sikh Gurus, Hindu mythology and comics published by Amar Chitra Katha from my parents and grandparents that would influence me to draw. The Sikh culture is an intrinsic part of my life.

Having been born into a practising Gursikh family, my education in the Sikh way of life began through my parents’ daily life and actions through a long lineage of Amritdhari Sikhs, which can be traced back to many generations in my immediate family. In the early 90s, the Sikh community built the first Sikh Gurdwara “temple” in Ilford, an old factory building converted into a temple step by step made by hard-working men and women living locally who would give their time when they could. I would draw people around the temple doing various activities with a pencil and paper. It was quite an exciting place to be as a child; there was a real sense of togetherness.

I saw specific values being practised, such as Langar, a communal kitchen of the Gurdwara, which served free vegetarian meals, symbolising equality. A practical part of the Sikh faith, which saw all people, regardless of religion, caste, colour, creed, age, gender or social status, eat together as one, was founded by Guru Nanak Dev ji in the 1500s in Punjab — shown in the painting Langar, 2022 at the exhibition Let’s have (a) look then at the Artist Room. I particularly loved Indian paintings from the Mughal and Sikh empires; when I visited the V&A, the powerful imagery and beautiful colours left a mark on me that I could not forget.

I was astonished to discover that I belonged to a vibrant culture and that the Sikh Empire under the rule of Maharaja Ranjit Singh was at the height of Sikh Arts, a golden era. I was sad to learn these were just memories of a brighter past. I belonged to a beautiful culture, and now it seemed our culture was just a shell of itself since the British Colonies’ impact on India. My paintings reflect my world and are an accumulation of life’s experiences over time, from my ancestors to me.

KA: What interests you in miniature paintings, in particular those produced during the Mughal Empire?

JSD: Indian miniature art has always been a constant source of inspiration. Even when my early paintings were inspired by Western art, I felt more honestly connected to the style of Indian Miniature and its unique sense of softness. The Mughal Empire produced some of the finest artists to date; in particular, I am a big fan of Bichtr, a 17th-century artist under the patronage of the Mughal emperors Jahangir and Shah Jahan. His finesse in drawing and composition is unmatched even amongst his peers; he is a personal favourite painter of miniature art, and his paintings work as a great comparison point for my paintings, a level I hope to achieve.

What I particularly enjoy about Mughal paintings is the sense of realism with the faces, hands, plants, and objects. I enjoy the mix of miniature art’s traditional style, colours, concepts and perspectives. It is relevant today, almost like a Miyazaki animation blended with the magical world of South Asia. I am fond of the works of Mughal court painters Ustad Mansur, Abu Al Hasan, Bishandas and Farrukh Beg. Other influences from the Sikh court are Bishan Singh, Kapur Singh of Amritsar, the family workshop of Nainsukh of Guler, Imam Baksh of Lahore and Ram Chand of Patiala.

KA: What is the thinking behind the selection of works included in your current presentation at The Artist Room?

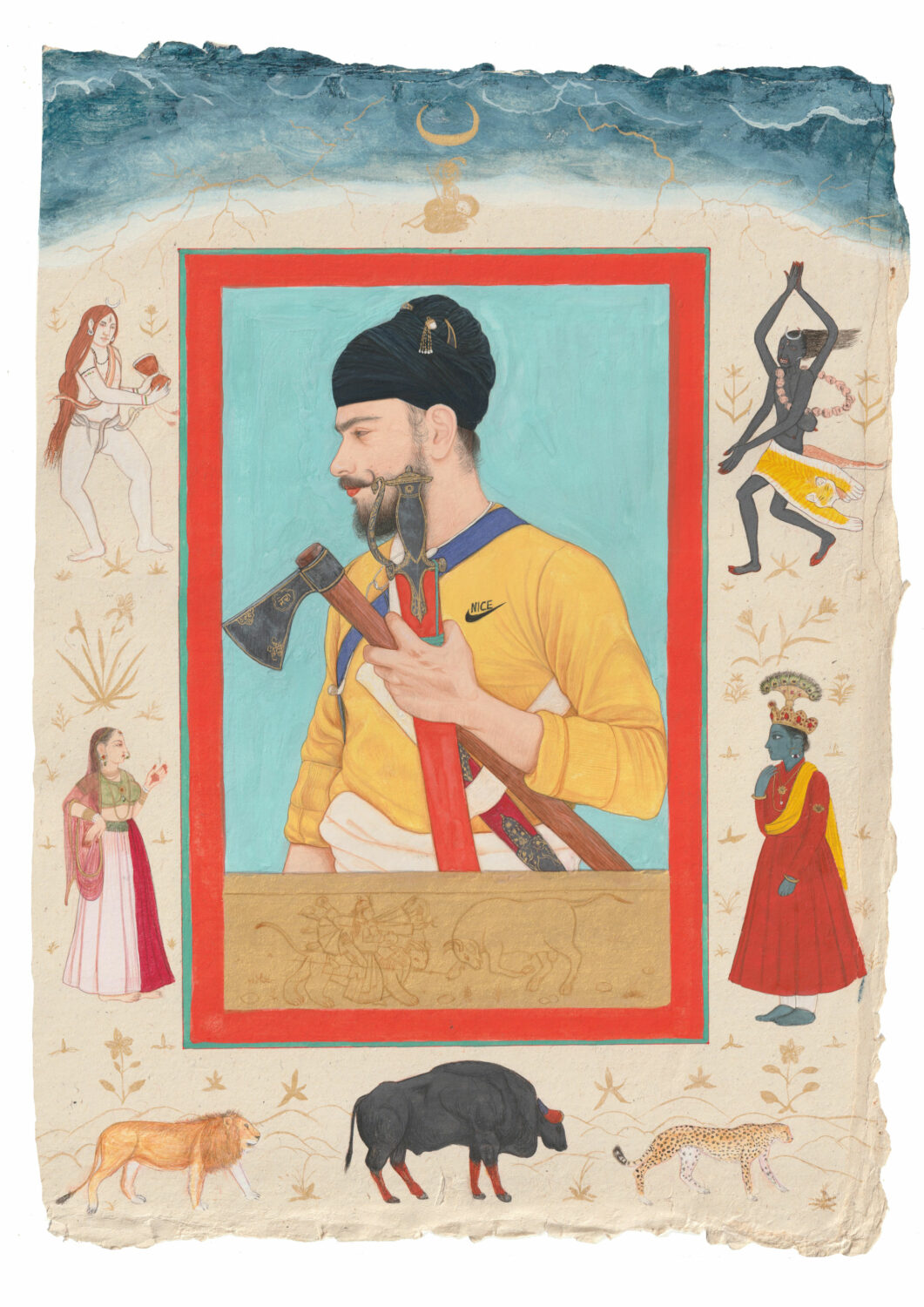

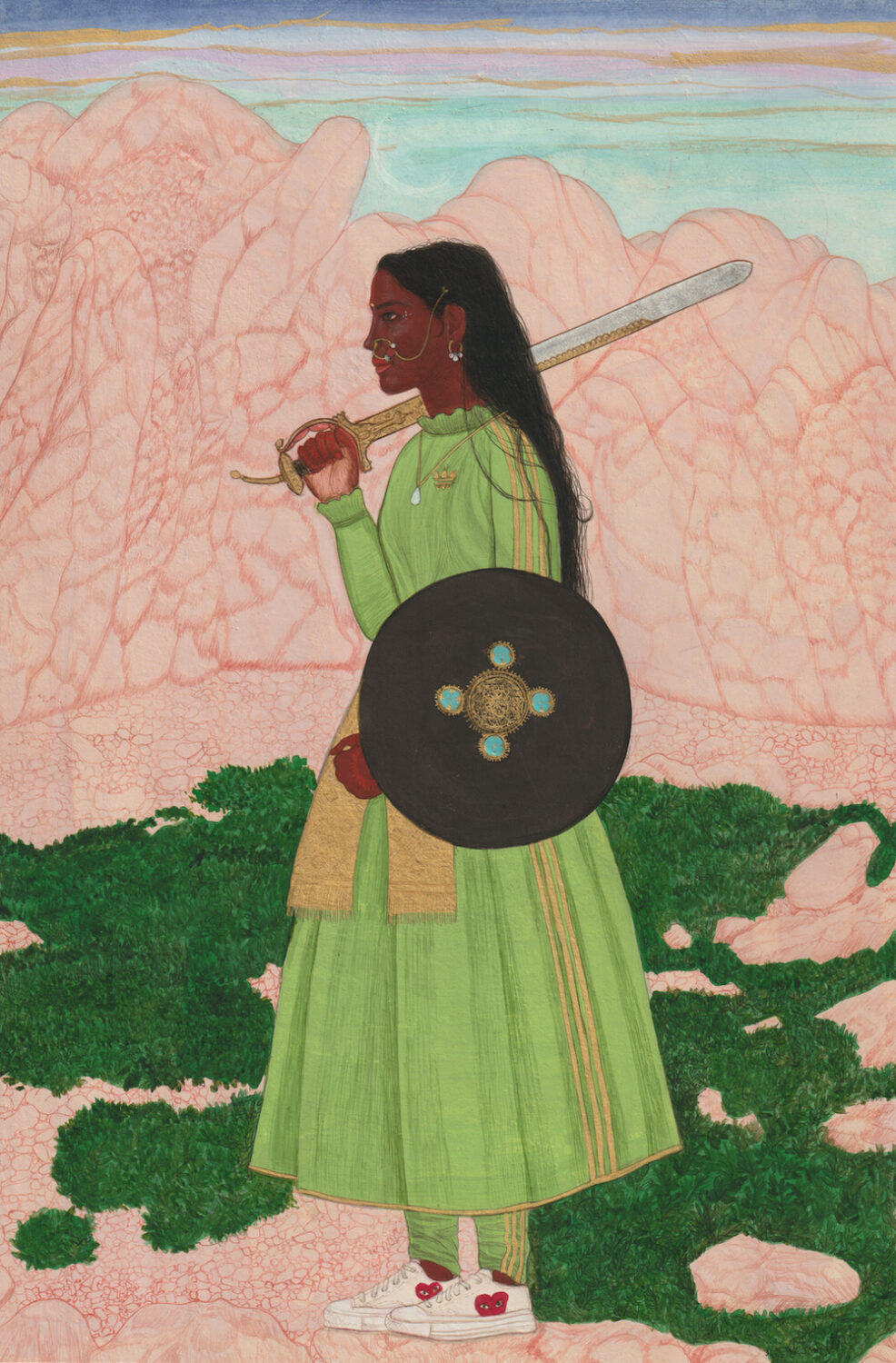

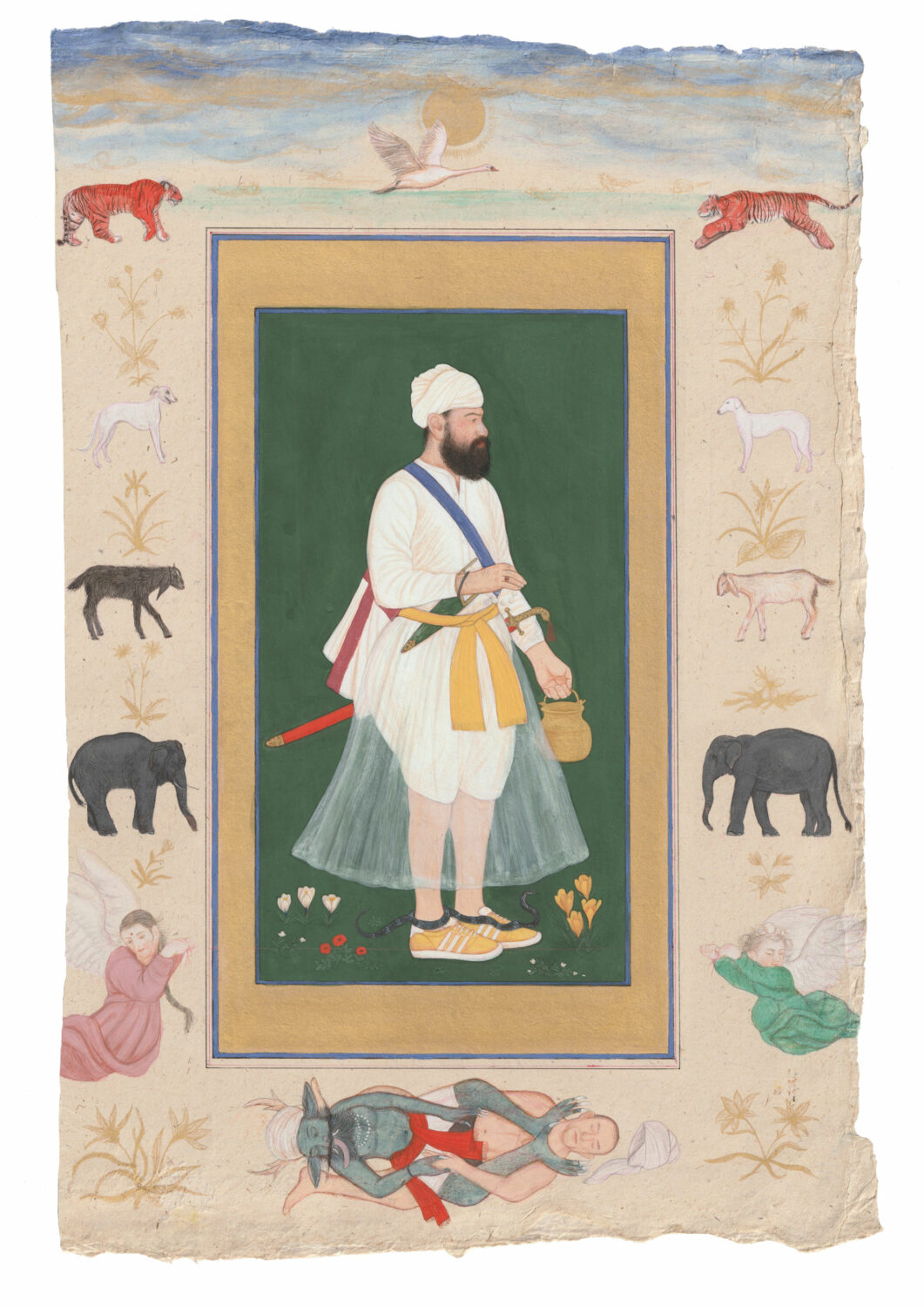

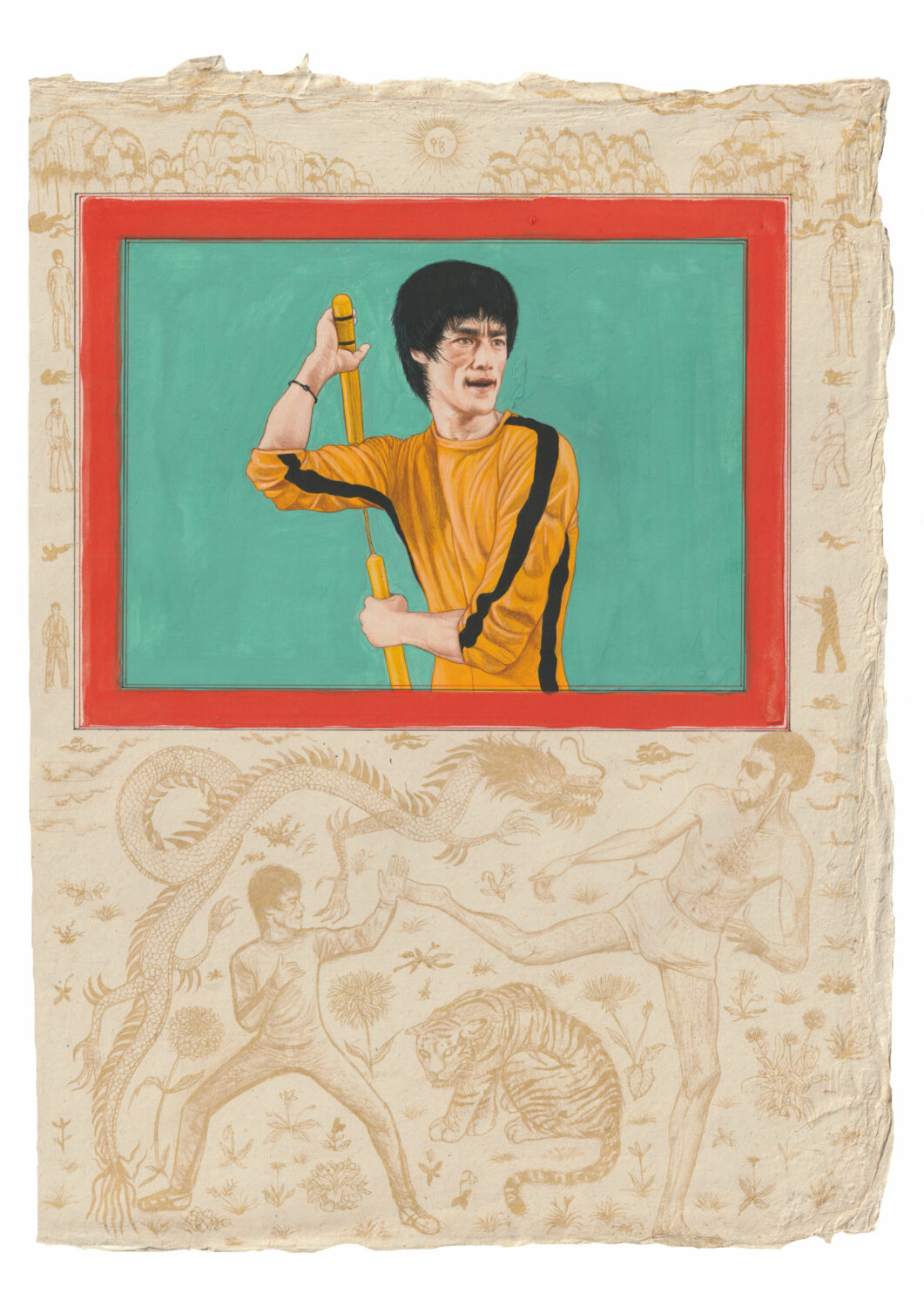

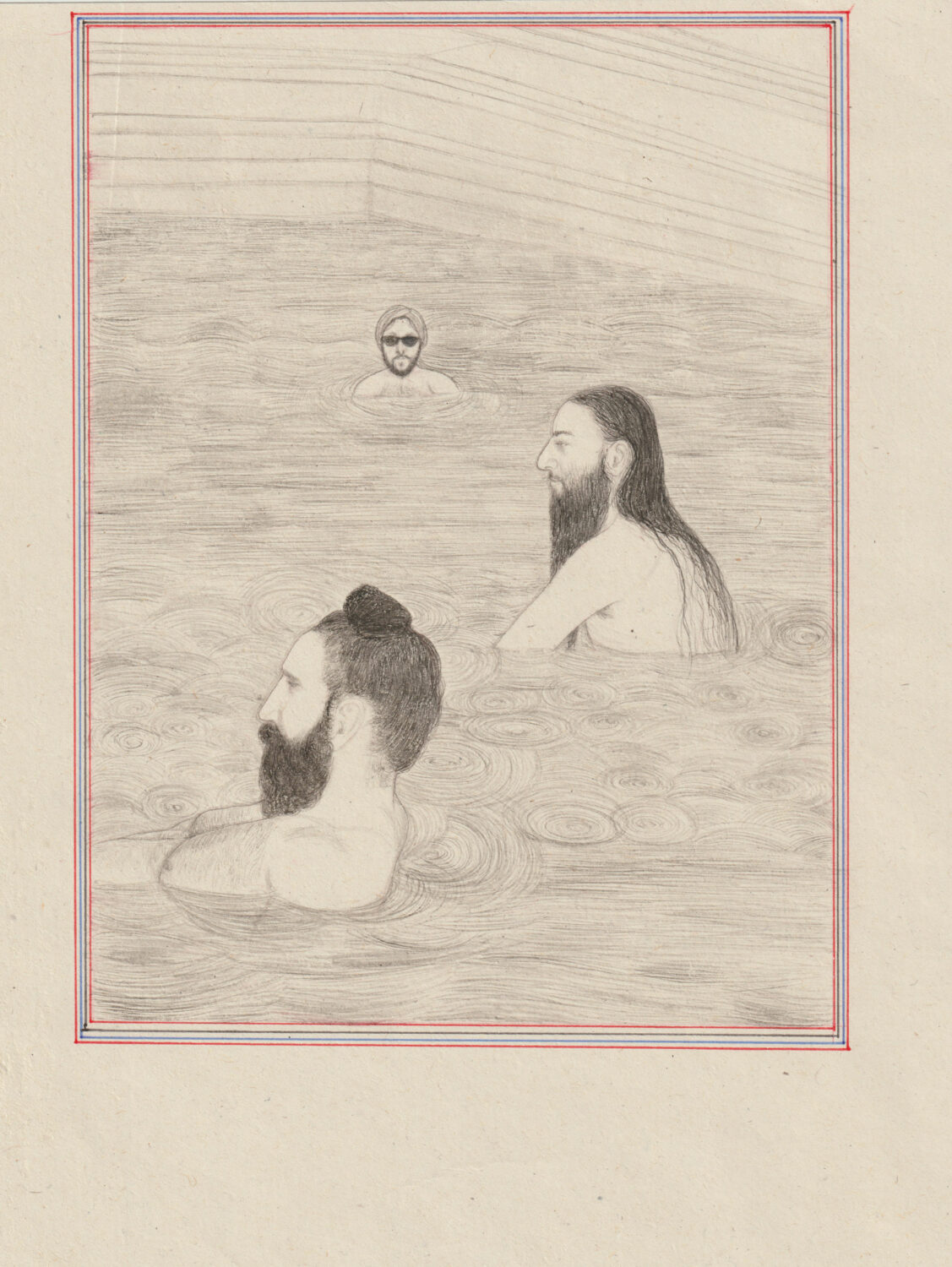

JSD: The title, Free Flowing Forms, was humorously decided as I visited a Gurdwara in High Wycombe with my wife Johanna. On the notice board there was a funny text describing a Sikh male with a “free flowing beard” who is a teetotaller vegetarian and abstains from alcohol and tobacco. These are some tenants and lifestyle choices followed by the Sikhs. The paintings in this exhibition at The Artist Room are a selection of portraits, from Jodha, a young rapper from Punjab, to the martial arts Icon Bruce Lee, A man in a Silk robe and the Goddess Durga. The paintings are next to studies of flower arrangements I see around the house arranged by my wife and fellow artist Johanna Tagada Hoffbeck. The flowers are grown in our allotment. Each painting is carefully selected to piece together the world within and around me.

KA: Could you expand on your embedding of present day references, often through nods to recognisable branding, in your work?

JSD: Visiting my local Gurdwara in the U.K. since childhood and going to India quite frequently, I enjoyed watching nature, whether it was the gentle wind moving the trees, a pink sunset, a cow minding its own business, a beautiful flower blossoming among a plastic trash bag or the people, these observations make their way to my paintings. The elements in the work are what the subject usually would wear or from trends that I have witnessed and find amusing. Each person in the paintings is an existing person; sometimes, I would illustrate them to play a particular character from the past. Some people in the portraits are my family and friends or people I find interesting. Like the court paintings from the past, I visit people I want to paint, for example, The Brothers from Leeds, 2023, currently exhibiting at Free Flowing Forms in The Artist Room, to make reference sketches and photos that would become a painting.

KA: What attracts you to wasli paper as a surface to work on?

JSD: I used to work on large cotton or linen canvas paintings early on in my career, using oil paints, mixing colours and applying them on a surface that gave a grainy texture. However, as I learned the language of Indian miniature art through attending workshops, lessons with various teachers, and a lot of experimenting, I realised the techniques and materials were different from what I observed earlier on; this is how the Indian miniature paintings get their unique flair as opposed to other methods of painting — there is a certain smooth and soft quality only seen in that painting form.

During a primary school trip, I was inspired by the Indian paintings I saw at the Victoria and Albert Museum. However, to this day, they are still labelled simply as opaque watercolours on paper, giving little insight to the viewer into what specific materials are actually used. It is painted with natural pigments from plants and stones on handmade wasli paper. A paper commonly used in South Asian miniature art practices is made from wheat flour, layered, glued together, and then rubbed down to create a shiny, smooth finish. I enjoy that this process allows one to paint in minute detail, which helps my painting to have finer details, such as the hair of one’s eyebrows or the delicate petals of a flower.

KA: And what are you currently reading?

JSD: I am currently re-reading Turning Point: 1997- 2008 by Hayao Miyazaki; it is a collection of essays and lectures gathered over the years. Reading the thought processes and inspiration behind one of the most legendary animators alive today is inspiring.

Recently, my first publication on my artistic practice has been released, titled Growing Long Growing Deep, published by Poetic Pastel Press, edited by Johanna Tagada Hoffbeck and T.S Wendelstein, designed by 75W Studio with a text by Laurie Barron and printed in England using vegetable inks.

Feature image: Jatinder Singh Durhailay, The Chakravati man, 2022