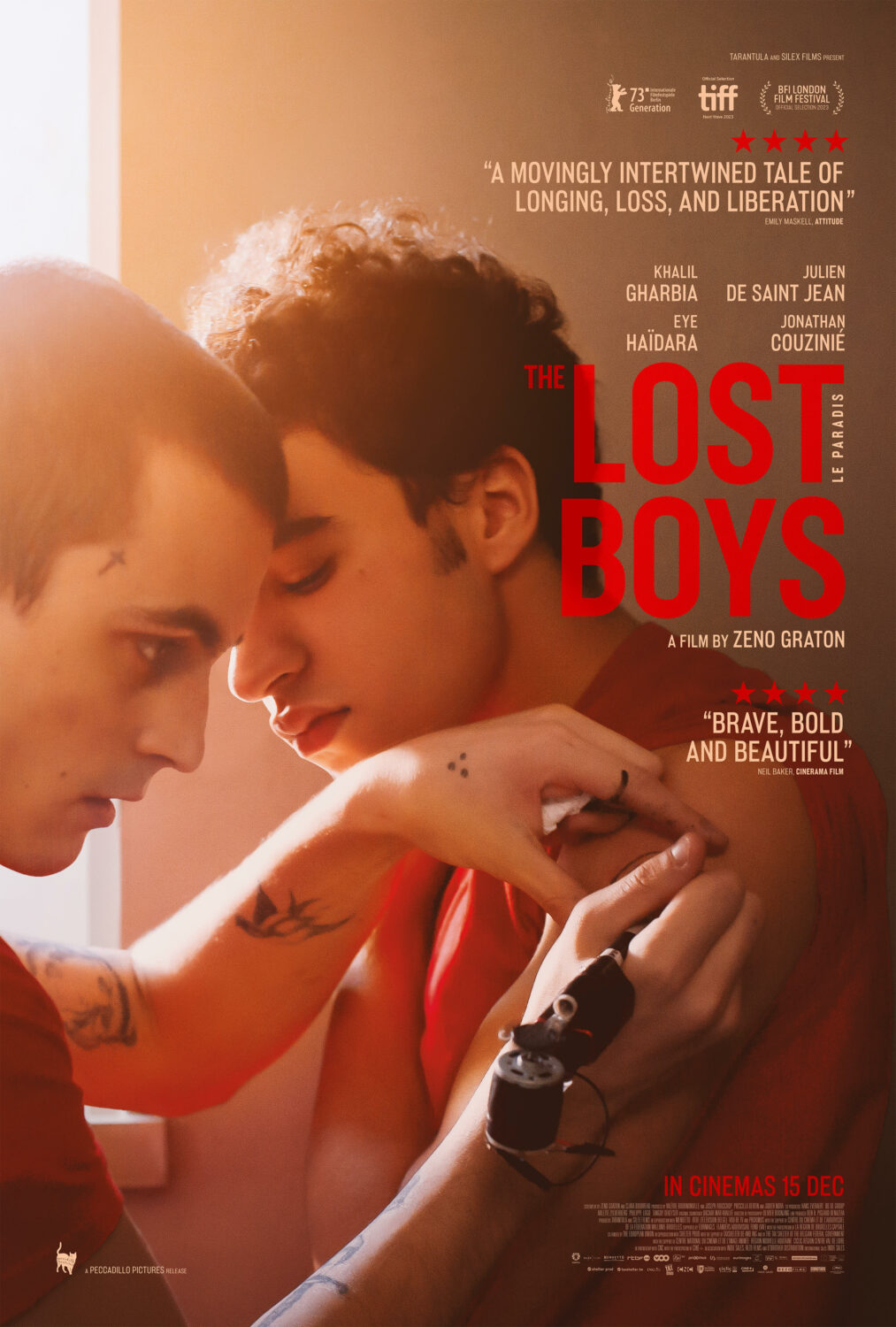

Director Zeno Graton on ‘The Lost Boys,’ a Queer Love Story Eschewing Shame

By Keshav AnandBorn in Brussels and of Tunisian heritage, film director Zeno Graton presents his acclaimed feature debut, The Lost Boys. Starring Khalil Ben Gharbia and Julien De Saint Jean, the film tenderly tells the story of a burgeoning relationship between two young men in a juvenile detention centre. The captivating project, which received its world premiere at the 73rd Berlin International Film Festival, will be released in UK cinemas this week, on 15 December 2023. Ahead of the release, Keshav Anand spoke with Graton to learn more about the director’s ambitions, the casting process, his favourite films, and more.

Keshav Anand: Why was this the story you wanted to tell for your feature debut?

Zeno Graton: I had already done some short films revolving around the injunction to heterosexuality, virility, masculinity, particularly toxic masculinity, and I wanted to continue exploring this enquiry. I was trying to make a love story that I would have liked to have seen when I was young. I was inspired by Jean Genet who really helped me write and also think about myself as a queer person in a more positive way – he was also very political and really became a mentor for me.

The imaginary of the prison system was also something I found very interesting to research about because I had a cousin who was placed in one of these facilities when I was young. I felt there was a huge subject there because it was a very taboo thing in my family – these kids are really despised and what happens behind these walls is made invisible by our society. I wanted to use cinema to open a window to these places, and try to make them seen. So I mixed those things and it created The Lost Boys.

KA: Unlike a lot of queer love stories, this telling doesn’t revolve around inhibition or shame. With that in mind, I’m curious, what was the thinking behind showing the first kiss early on?

ZG: It was very important to the team and I to make a little step ahead in the path of queer cinema. Meaning that when I grew up, I was only seeing stories that revolved around the overcoming of shame and inhibition – and I think that is a story that is very important but that new stories can also now be told. I think these stories need to have more room in the landscape of queer cinema because stories revolving around shame continue to tell the fact that gay people are victims and its kind of shadowing any other aspect of their identity – also, it’s not really talking about the power of this new generation that I was witnessing.

This generation that is now twenty years old is very different to when I was that age. They grew up with a lot more representation around them, with more legislation passed in the benefit of queer people. But mostly I think it’s a matter of representation and I think that social media too has helped to make them feel more ok with themselves – and therefore more fluid and less taken by this toxic masculinity that is often revolving around gay spheres.

In my neighbourhood in Brussels there is this street where its only men’s bars with big dudes with muscles around, very typically masculine guys, drinking beers, being very stiff, talking loud – and there was a new bar opened by very young people in the same area recently, for non-binary people, trans people, femme gay guys – there is a policy at the entrance where you are asked your preferred pronouns. There are nice cheap cocktails, there’s pop music and drag shows. This place is really something new for the area and it’s attracting a lot of people. Seeing these types of places opening, I wanted to make a teen love story that I would have wanted to see when I was a teen, or even now.

I wanted to create something that honoured this new generation and their fights and where they are now. I think also that there is so much conflict happening after a first kiss than before – and this was something I was never told as a gay guy. I was told in the movies and even by society that when you accept yourself that everything is cool. And you make this big leap of faith in your life but then what happens after that – the complexity of two people trying to love each other.

This was a conflict that was being written about for centuries. I wanted to explore the many conflicts that two people could experience – I’m talking about longing, about forgiveness, abandonment – without forgetting the political aspects of being a queer person in this society, meaning you often still have to hide in certain spaces or be discreet. For me, it’s time to have queer stories that are real, politically, not ignoring a homophobic society, but that also give power to our community.

KA: Could you expand on your experience visiting juvenile detention centres while researching for the project?

ZG: When I was authorised to enter these places, I witnessed things that really changed my life. These kids were super clever, super witty and full of life. What I was reading in my theory books was that people in prison are people that society doesn’t want to see – it’s really about social issues and racial issues. It’s about people who are not profitable for our capitalist society. I was meeting kids who were telling me that their fridge was empty and that they need to steal to eat – it was a lot about social inequality.

I needed to witness it with my own eyes to be able to talk about it confidently through the film. It wasn’t about making a moral film or documentary, so I didn’t spend a year there – it’s a fictional love story. But even over my two visits, it was enough for me to be able to capture the architecture of the place, the schedules, the main dynamics. It was also a good opportunity to meet with the social workers who for me are heroes. It was important for me to show them as people who try to do their best but are blocked by very unfair systems. It was clear after my visits that the main bad guy, so to say, is the system itself – it’s not the human beings who are inside who are trying to make it work with their ideals.

KA: How has the work of French novelist, playwright and poet, Jean Genet, influenced the film?

ZG: The work of Jean Genet first inspired me because his characters are unapologetic about their queerness. And this was a very key element for me in writing this movie. As I said, the cinema landscape is saturated with queer guys that are trying to feel better in their skin and it becomes only really about that. Whereas in Genet’s work, the problem is external. It’s never about the interiorisation of this homophobic society. They are characters that didn’t allow that because they are very strong.

It helped me to read characters that didn’t allow that. I wanted to create that for the audience in my first film – to show that no, not all queer people are the victims, you don’t have to pity them, you have to live with them, and know them for who they are, which is a million things. Genet really taught me that.

KA: How did you go about building your cast and what interested you in the actors you landed on?

ZG: I knew I wanted an Arab leading character for Joseph, connecting to my Tunisian Sephardic roots. I wanted to portray a queer Arab leading character in the movie because for me, as a person of Arab descent, I’ve always seen Arab characters either being in supporting roles or in leading roles as people who are objectified, victimised or exoticised. It was important to have a character who is not an object in the story but a subject. He has his own drive towards men that is not blocked by his Arab roots because this is a bias that is racist and puts Arab people in a box. I think it’s dangerous to continue to display those representations.

I had to find an Arab guy that was happy to play in this movie and it was a revelation when I met these guys for the audition – I realised that this new generation was really ahead of my generation. Most of them were very deconstructed about their masculinity. And when Khalil [Ben Gharbia] entered the room, he told me about his heroes; he talked about David Bowie, Jim Morrison, Kurt Cobain – rockstars who really challenged masculine identity. He was nineteen when he did the movie and he was very mature around that – and that was important, to cast someone who was at ease with what was going to be played.

He’s a wonderful actor, intuitive and generous emotionally. He’s very connected with his tenderness, which is probably the main aspect for me, because I really wanted to show tenderness in this film. I find it more subversive than playing brutal sexuality. For Julien [De Saint Jean], he was very determined to have this role. He told me in the beginning how he recognised himself in the character and how he wanted to defend that in the movie. He was a pure joy and they had great chemistry.

KA: Can you talk about the role of music in the film?

ZG: I knew that I wanted to address race as an issue in the prison system though it would not be the main topic of the film. I didn’t want to use too much language to talk about that – there are moments that we do – instead, I wanted to use music as a way to emotionally channel the cultural roots of the main Arab character. It gave a sense of distance, a sense of longing, being someone in a prison who is cut out from where he comes from, his culture and his family.

We asked Bachar Mar-Khalifé, who is a Lebanese composer who I have loved for a long time, if he wanted to do it and he said yes. I gave him some poems by Rumi, a Sufi poet, whose poems are thought to be about a gay relationship that he had, as a starting point. I wanted to link Arab music with gay sex scenes – and that’s what we did. It creates a bridge.

KA: And to change topic momentarily, what are some of your favourite movies that you would recommend we watch?

ZG: Happy Together directed by Wong Kar Wai – one of the most magnificent movies I’ve seen in my life and a huge inspiration for The Lost Boys. And from more recently, Four Daughters, a film by Kaouther Ben Hania – it’s a masterpiece of mise-en-scène.

Feature image: © Peccadillo Pictures