Who are the Neo-Dada Organizers?

By Keshav AnandThe Neo-Dada Organizers’ destructive activities, often centred on the demolition of art objects, prompted critic Yoshiaki Tōno to coin the Japanese term “han-geijutsu,” translating in English to “anti-art.” In 1960, Japanese conceptual artist Masunobu Yoshimura founded the controversial art collective. Widely abbreviated to Neo-Dada, the group would meet at Yoshimura’s studio in Shinjuku, Tokyo, to plan their projects. During their short-lived existence, Neo-Dada were involved in a variety of artistic undertakings but remain best known for their unsettling live works.

Positioning themselves against established art forms and authoritative institutions, the collective was born in part as a reaction to the modernisation of Japan after World War II, a period of rapid change. As well as resisting the prevailing humanism and socialist realism prevalent in 1950s Japanese art circles, the group made known their distaste for the widespread adoption of foreign art trends like abstract art, satirising the fashions of the day.

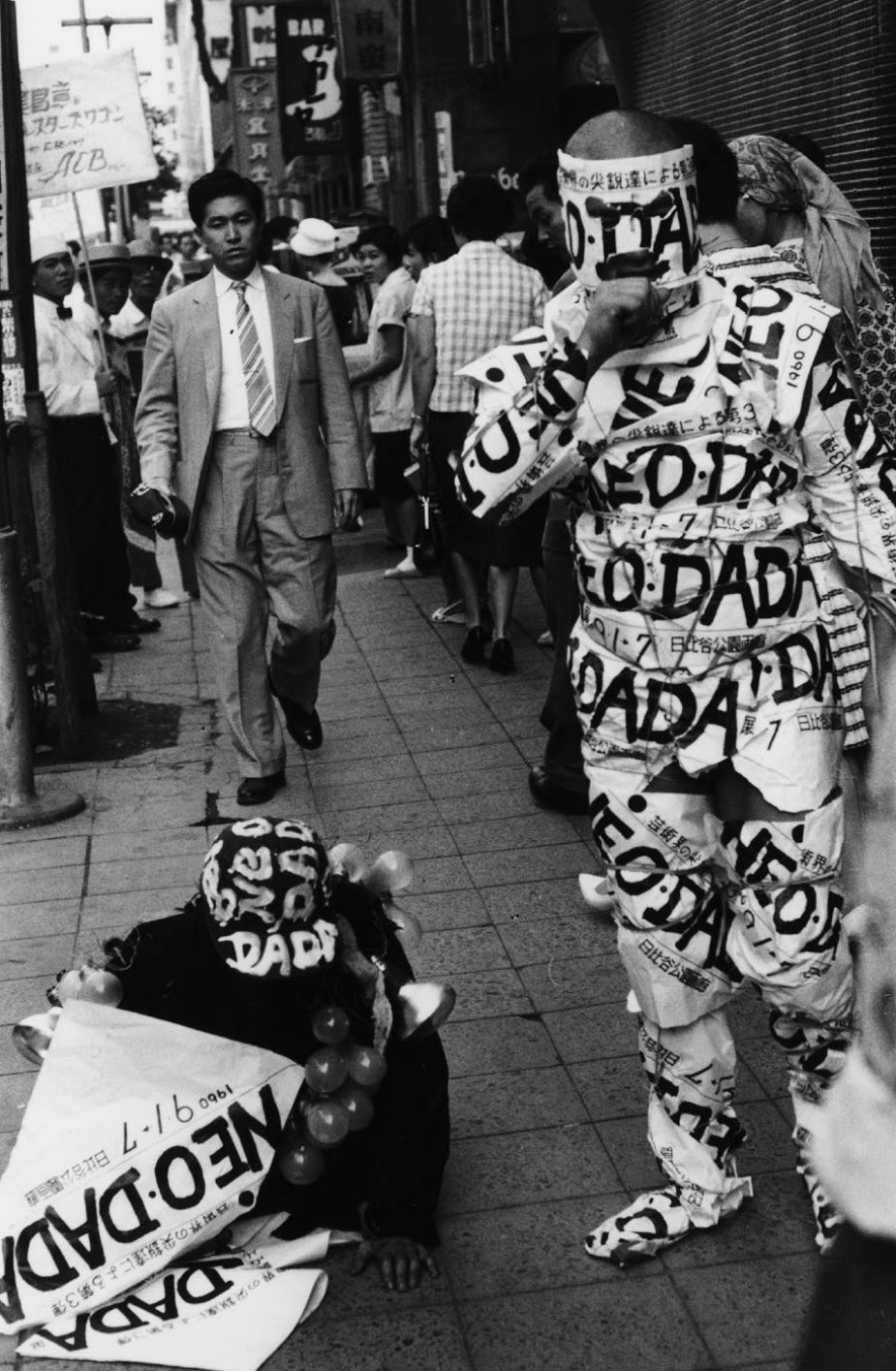

Filling galleries with mounds of garbage, rhythmically destroying furniture, their crashing sledgehammers and axes soundtracked by Jazz, or parading through Tokyo’s streets in various states of undress, the Neo-Dada Organizers’ oeuvre encompassed outlandish and subversive acts, inevitably drawing attention. Utilising the human body as their artistic medium, the group’s commanding performances sought to illustrate their discontent with the constricting Japanese art scene — while mirroring broader social shifts of the time.

Alongside their rejection of dominant art forms, the group protested the attempts of Prime Minister Nobusuke Kishi’s government to amend and prolong the United States-Japan Security Treaty, referred to as “Anpo” in Japanese. This initiative sparked widespread objection throughout the country; concerns arose from the treaty’s entrenchment of Japan in a military alliance with the US, leading many to worry Japan would be a target in the event of a nuclear conflict.

In 1960, the inaugural Neo-Dada Organizers exhibition took place at the Ginza Gallery in Tokyo. During the event, the group showcased found objects and waste material, accompanied by music and distorted sex noises. While a partially unclothed man wielded an axe to demolish the “works” on show, the cacophony of destruction was recorded and broadcast loudly onto the street from the gallery’s window.

At the same show, Neo-Dada presented a manifesto of sorts, comprising statements such as, “Neo-Daddists are uncultured… Neo-Daddists are not human beings… Neo-Daddists are a group devoted to artistic revolution… Neo-Daddists reject the abstract art movement entirely.” It seemed the collective’s aim was to establish a realm for new forms of art by actively dismantling everything before it. Their principles underlined the group’s commitment to what member Genpei Akasegawa later dubbed “creative destruction.”

Over the course of just one year, the lifespan of the collective, Neo-Dada held three exhibitions along with several happenings. Their divisive works quickly amassed attention, gaining regular coverage from the Japanese press. They inspired several other “anti-art” focussed collectives active later in the 1960s, including Zero Jigen, Group Ongaku and Hi-Red Center. Following the influential group’s dissolvent, several members and participants — including Genpei Akasegawa, Shūsaku Arakawa, Sayako Kishimoto, Tetsumi Kudō, Natsuyuki Nakanishi and Ushio Shinohara — went onto pursue independent art careers.

Feature image: Kinpei Masuzawa (left) and Masunobu Yoshimura (right) advertising the third Neo Dada exhibition in Ginza, Tokyo, September 1960. Image via Pinterest.