Chef Artist Behzad Jamshidi’s Life in Objects

By Cole WilsonChef Behzad Jamshidi began his career in 2016 when he moved from Vancouver BC to New York, the city he still calls home.

After working in some of the city’s most well-known and celebrated kitchens, in 2018, Jamshidi started the Moosh platform to create what he calls more “meaningful collaborations and representation for the marginalised New York hospitality community.” Through this organisation and anthropology lab, Jamshidi now manages major cultural research and development programs in collaboration with international governments. All while constantly “working hard to make my Persian mum proud.”

Below, in his own words, Jamshidi shares his most cherished possessions.

Knife

The very first job interview I had when I came to New York was at Le Bernardin.

The airline lost my luggage on my flight from Vancouver and I got stuck wearing a baby blue J.Crew suit going into my interview, not knowing that they were going to throw an apron on me and put me on the line.

Ahead of getting there I was staying at an AirBnB in Chelsea. In my packed (and lost) luggage was a Wusthof knife I had from school, which I also had emblematically tattooed on my body because that’s the kind of decision a 17-year-old would make. Anyway, I figured that if they were going to take me seriously from the get-go, I needed to have a serious knife.

So I walked down to the Chelsea Market and went into one of those unassuming kitchen stores, the kind of place that your mom would go. The guy was sitting on this giant display of all these different knives and stuff and we got into a little conversation.

I had like $500 left for anything and everything and that I was hoping that this job interview would help kickstart life in NYC.

He pulled out this incredible knife and was telling me about the knife maker who had passed away – it was a piece that he was most proud of and something that he had curated in the shop that wasn’t for sale. We talked a little more and he asked me how much money I had and I told him about my $500. Knowing the knife was worth more than that, I gave him my $500 and he handed me the knife. He sold it to me in good faith.

It was the very first thing that the sous chef noticed at Le Bernardin. I got thrown onto the hot line and started cooking, wearing this baby blue suit under my white chef apron on the line and then Anthony Bourdain walks in as I’m cleaning clams on the station and dead eye looks at me: “Who the fuck are you?” he says.

“I’m this kid from Vancouver.”

And he’s like, “What are you doing here?”

“I’m here to learn seafood.”

And he’s like, “where is your family from?”

“My family’s from Iran.”

And he’s like, “you don’t need to be at Le Bernardin to cook French food, there’s enough people to cook French food.

“You should take you and your fancy knife and start cooking Persian food for people.”

I had tried to do so much to be seen in the hospitality space and didn’t realize that the thing that was inside me, which is my culture and where I come from, is the thing that people will always see first. I think it helps create a distinction between myself and other cooks, because I have my own story to tell. It’s not how I’m dressed or the tools that I show up with, but it’s the person I get to translate across the table, the food that’s most important to me.

I’ve nurtured that in my career the most and do everything from this perspective of my Persian culture, not just because Anthony Bourdain said it, but because it felt like the environment of New York wanted to celebrate that uniqueness that I had inside me before I tried to make it about anything else.

That knife has cooked thousands of meals – it was my one knife until I could afford another one.

Meat masher

So this is a wooden meat masher that my mom was using the night that she met my dad. They met in Toronto and she was making this traditional dish called dizi, which is pieces of lamb and chickpea with spices cooked in an earthenware pot.

After it’s all cooked to tender, you take the meat masher and you kind of make a pulp out of it, and it turns into this hearty, meat-mashy stew, and you serve extra broth and semi-dried bread on top.

But it turned into the gavel that my mom threatened us with when we were kids, like to hit us or whatever.

And when I left Vancouver when I was 17 to come to New York, it was just one of those intrinsic tools where it had so much sentiment in my family and for my parents, but also my mom being the matriarch and having a very tough personality.

But her being the kind of person where food was an extension of her love, whatever she couldn’t communicate in words, it always found its place inside meals.

And so this meat masher/gavel is very emblematic of who she is as a person.

Roman tile

So this is an old Roman roofing tile from Napoli. I have a very close friend there and she lives in this place called Vico Paradisiello (little paradise). Something I learned from Neapolitans is that even if you don’t always have the most idealistic materials for things, you can be creative with your resources.

There are a lot of beautiful examples throughout history of how things can be used beyond their intended purpose and for me this tile is the grounding space for a pot or a pan. So this is always the thing at the centre of the table. It’s just how I translate my experiences [travelling to] Napoli and the communal cultures there. Tiles for me are the pieces of the mosaic that I build when I come back to New York. I try to pick up a tile in every country that we travel to. Japan, Portugal … If I can get on the roof I’ll take one.

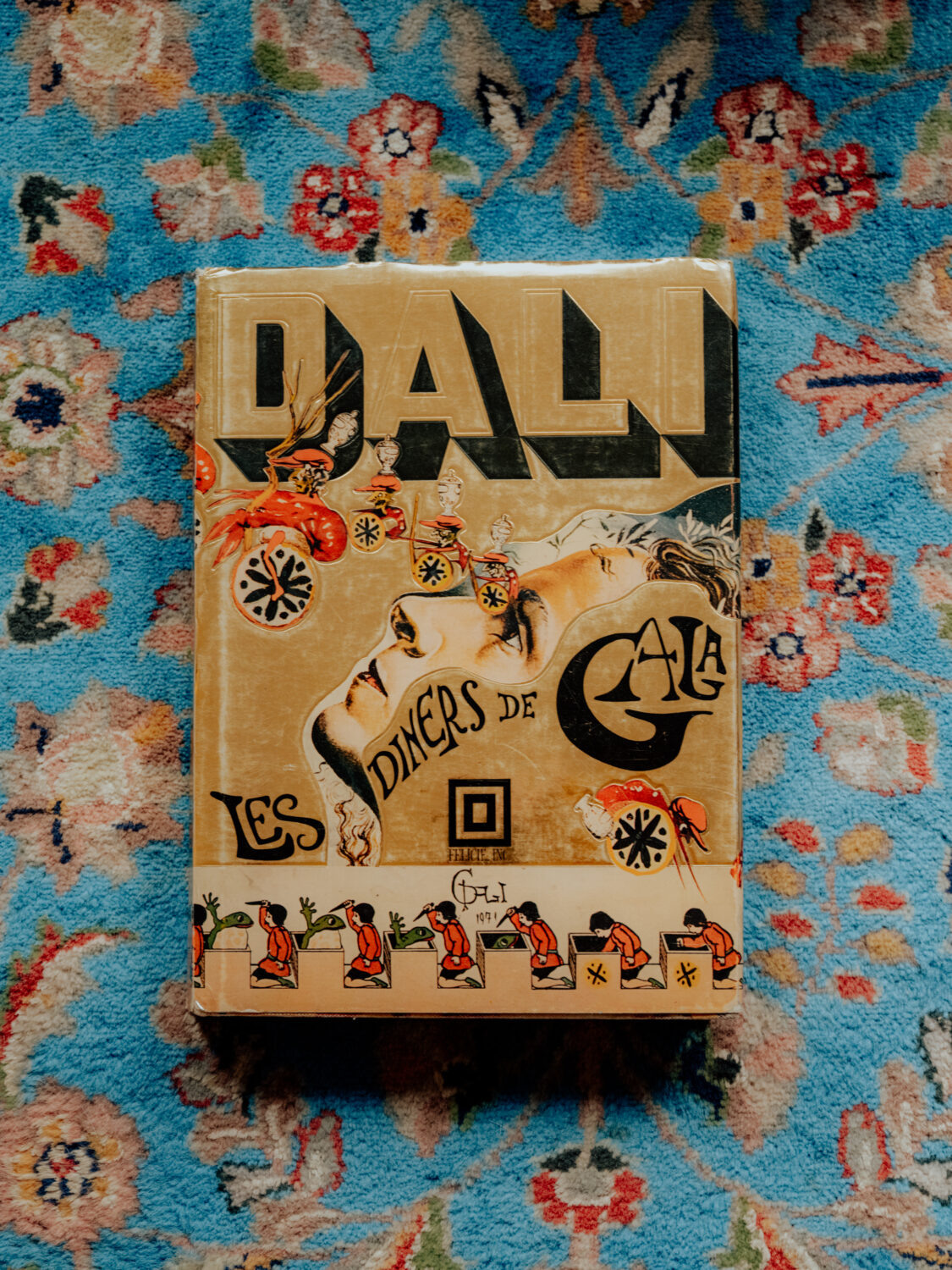

Salvador Dalí’s, Les Dîners de Gala

My favourite cookbook of all time is the Salvador Dali cookbook, Les Diners de Gala, which he dedicates to his mistress Gala, who was known to be a hoot back in the day.

There’s a preface inside of this book where Salvador Dali is talking about his experience at a diplomatic dinner with the Shah of Iran, and he discusses surrealism in the way that we express abundance in our food; he looked to Persian food and culture with reverence.

The thing that I love most about this book is its philosophy, that I think drives everything that I touch – that food is diplomacy, that anything can be really constructive and done through the harmony of bringing people and perspectives together over the course of a meal.

And so in the way that he writes about his recipes, which are all one free-form thought and instruction, he’s not describing to you when the onions are done, but he’s telling you to have sensibilities and feelings of your own experience cooking those onions; assessing your feelings while you’re sweating them out to the point where, does it give you a pretty aroma; does it have a colour that encourages you to go on to the next ingredient? He’s actually asking you to use your own judgement and humanises it in a very beautiful, poetic way. He’s getting you to cook the dish, not from a step-by-step process, but almost like a movement, a feeling.

And that’s why this cookbook has been so emblematic for me. Before I start other projects, before I write about food, if I just need to revitalise something inside of me, I’ll read the recipe for Oasis Leek Pie. It’s a ridiculous dish, but the way that he talks about it coming together is something that always reaffirms to me why it’s so important to make sure that your emotion is translated across what you do inside food.

Dali’s the source of inspiration for me that always keeps my instincts juvenile in the best way possible. I can have these childlike ambitions while still being a professional chef, having charters and systems and programs and stuff, knowing that there’s also a freedom that I need to continuously be accountable to inside myself.

Journals

My next little culinary memento are these journals that I kind of dedicate to trips and specifically to teachers.

The very first journal I created was to help archive recipes that my mom cooked for us growing up; all the different variations in Persian stews, bread recipes, etc. What was also interesting for me to learn were the different spices and also the different dishes in and of themselves that she would cook that were inspired from other cultures.

I think it really gave us an international perspective to be able to have a Tunisian dish at our dinner table once a week, or to be able to have something that was Jamaican, Ukrainian piroshki for breakfast, or Turkish dumplings.

And for my mom to take the energy and the effort to build spice blends, preserving her own harissa and not using one utility spice for everything but having a ras el hanout for a specific recipe. Everything down to the bakeries that we would go to were things that were just intrinsically put into our culture. It really helped open me up outside of the dogma of cultures wanting to create borders around their food and ingredients and learning that there has been so much gastronomic exchange and collaboration across different cultures and countries throughout history.

You know, there are so many things inside Persian food that are borrowed from other places: Our birthday cake is the roulette, which is French. Noodles that also came from Asia and Southeast Asia, the Rishta style, which is actually a soba noodle that we use in our New Year’s soup. These books help reference not just the recipes, but the integrity of the ingredients that shape those dishes.

And so these journals were an inspiration for us to create our own anthropology journal called “Humanities”, which was inspired by the integration of culture that we saw when we were in Italy. Humanities for us is a way to take these rural cultures and these domesticated foods and recipes and give them to people in a format that can inspire them to take those recipes then into their own homes and find very simple and uplifting ways of exploring other people’s cultures that aren’t ostracising by ingredients and aren’t difficult to translate for home culture.

If you buy a head of cabbage at your farmer’s market, you now know 50 different ways that you can process and cook it – that type of resilience is really important.

That’s the thing that I learned from my parents because we grew up in incredibly poor means, but they looked to other cultures – that influenced the way that we cook so that we never had a potato the same way twice. I can’t express enough how important that was for my childhood and how much that crafted my philosophy: I don’t think I would have become a chef if it wasn’t for the type of variety that my parents were so affluent in sharing at the dinner table.

Mug

Jono Pandolfi is probably one of the most incredible ceramic artists that we have here in the United States; Italian in background.

He and his brother Nick run this studio over in New Jersey city where they originally were curating and creating plateware for some of the best restaurants in the world, so you’ve seen their things at say, Eleven Madison Park. And he has a format, a signature style that’s very recognisable. But one day he decided that he needed to make this mug. He had it in this archive of second or after thought plates, things that don’t actually make it to the commercial orders. And every once in a while, I visit and go on a deep dive – like it’s a yard sale and I go back there and I find really interesting things that I pay them whatever they want for it.

This reminded me that there’s a thing that we have to do for our business: we have to commercialise ourselves as artists for the sake of surviving.

But then there are other things, almost like bubbles that form in our chest. They’re creative things that we have to do to re-inspire; not change the form or the shape of what it is that we do as artists, but intrinsically there’s a feeling in us that can be a little bit more enriched from exploring different aptitudes of creating the same thing. Like cooking a dish with a different perspective, not even necessarily doing it differently. All the ingredients in the mise en place can be the same, but it really is this inherent feeling of being true to yourself that I think every artist is responsible to.

I’m incredibly inspired by Jono and how he’s always there to reinvent himself, yet still remaining consistent in his execution.

Billie Holiday: Strange Fruit record

Every time I step inside of the kitchen, I play Billie Holiday, even just for the first song.

Her whole life was just full of adversity and she was singing these beautiful songbooks: She represents the transcendence of an artist because she had the bravery to talk about and tackle difficult themes in a difficult time.

She would use these alluring, maybe popular songbooks to set the stage for the moment that she would sing Strange Fruit. And no one wanted her to sing that song.

I think part of her disintegration, her life, her career, her health and everything else was behind the stubbornness that she had to prove a point through her art.

It reminds me not just about the accountability of making art or working through artistry or being an artisan and cooking, but doing it to also make a change, doing it to represent people that may not have the voice that they need – that we’re, as artists, occupying a space of attention for people.

It’s not about the temperament or the mood, but it’s the fact that when she did have the space to make a statement, she took it and did it very bravely and very unapologetically.

It doesn’t mean that we need to be making a statement with our art all the time, but when there is an opportunity for us to step back and to look at what’s going on, I think as artists we’re socially responsible to give that moment a voice and to represent people who are underrepresented, to give them a chance or a platform if we’re able.

For me, that starts with my Middle Eastern culture and my ethnicity as an Iranian.

All photography by Cole Wilson. This interview has been edited for clarity.