Interview: Soufiane Ababri Challenges the Dominance of Western Narratives in Queer History

By Keshav AnandOpening on 13 March 2024, Moroccan-born artist Soufiane Ababri’s first solo institutional show in the UK is set to transform the Barbican’s Curve gallery through a site-specific and cross-disciplinary presentation of work. Based between Paris and Tangier, Ababri’s practice spans drawing, sculpture, installation, and performance. His works borrow ideas from philosophy and sociology, as well as, perhaps most overtly, gay subcultures.

Alongside a new series of wall-based works, an immersive performance responding to the shape of The Curve will explore the power architecture can hold over our bodies, referencing the history of nightclubs as sites of resistance for the queer community. To learn more about Ababri’s work and the upcoming exhibition in London, Keshav Anand spoke with the artist. Ababri’s words have been translated from French to English for Something Curated.

Keshav Anand: Your work astutely draws from both Western and non-Western canons and experiences — I’m curious to learn more about your background.

Soufiane Ababri: It’s definitely linked to how I define myself as a person and as an artist. I am a gay, North African immigrant, from a post-colonial generation and raised in an Arab Muslim culture. These things are all paths that I have followed throughout my research, both artistic and theoretical. But “background” is not a fixed notion; I consider myself to be in a constant state of becoming, constructing, and deconstructing.

KA: How have you approached utilising the space of The Curve gallery for your upcoming exhibition?

SA: Artists are often expected to make exhibitions that respond to their past work; for me it’s a little different since I like to do exhibitions that react to the place that invites me — a contextual proposal. For The Curve, the proposal came to mind very quickly, as soon as I received the architectural plans of the gallery. The shape of the space seen from above makes a visual link with a letter of the Arabic alphabet “Zaïn” (“ز”). It is the first letter of the word “Zamel”, which is a slur used against gay men.

This connection speaks to the research that I have been doing for years on stigma and humiliation as a critical factor in forging the subjectivity of marginalised communities, whether in terms of sexual orientation or race — for me, it’s both. So I tried to see what it could mean to replace, for example, terms like “critical perspective” or “analysis” with suspicion or paranoia, and to explain using architecture to assert myself. I want to turn the idea of the insult around by sublimating it, by transforming it into a celebration.

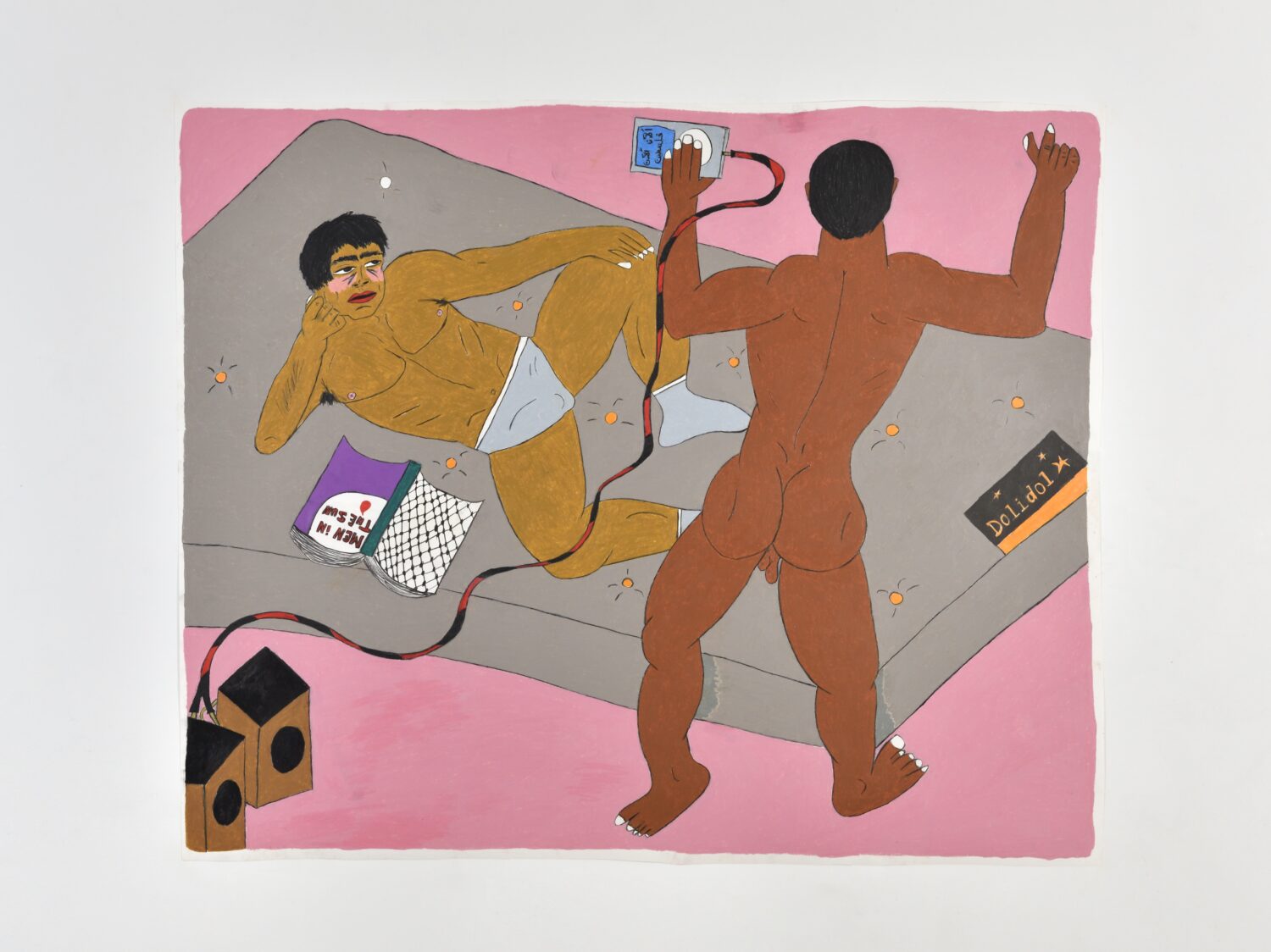

KA: Can you tell us more about the characters you depict — who are these figures?

SA: The characters mainly represent a resistance to the masculinity and exaggerated virility that I have been exposed to since my childhood, but they are also there to make visible a new way of socialising, of asserting the visibility of racial and sexual minorities. There is also a side to my work which acts as an “invocation” of a family of writers, artists, gays (living or dead) with whom I correspond fictitiously in my drawings, like colleagues with whom I collaborate. Sometimes I am critical of them, or I enter into family, friendly, romantic relationships with them…

KA: Could you expand on the influence of thirteenth-century painter and calligrapher Yahya ibn Mahmud al-Wasiti on your new work?

SA: I wouldn’t say that his work has an influence on all of my practice. But for this exhibition, one of his paintings was important for the construction of the project. I was searching for the first work from the Arab or African world that, for me, on a subjective level, showed the beginnings of homoerotic representation. I wondered how to historically point to the beginning of romantic friendships between two male bodies in Arab Muslim heritage. The specific painting referenced in this exhibition is Farewells of Abu-Zayd and Al-Harith before the return to Mecca, from ‘Al Maqamat’ (The Meetings) by Al-Hariri, c.1240 (vellum), Yahya ibn Mahmud al-Wasiti, Baghdad (13th century).

KA: Are you able to share any details about the site-specific performance you have planned for the Barbican?

SA: The performance considers a community of people (performers) who have decided to abandon their bipedal nature. They are outcast from society. But instead of being furious with this situation, they accept it as something beautiful. Being on the margins becomes, in their eyes, the beginning of a state of happiness. They begin to develop ways to no longer resemble the people on the other side, those in the centre. The first way they do this is by trying to cross spaces horizontally. Crawling or walking on all fours is a way to break with social norms. They are going to occupy and traverse a part of the space of The Curve, which represents an exterior of a club. They will cross the letter Zâyn.

KA: What are some of your favourite cultural spaces in Tangier?

SA: I really like the walk along the corniche between the port and Marcala beach. I like the Hanafta café in the evenings when music groups come to play, and the music-bars of the new towns that come alive after midnight. But I feel my experience of those places is different to the one of many Western tourists, who tend to exoticise them.

Soufiane Ababri: Their mouths were full of bumblebees but it was me who was pollinated runs at Barbican’s The Curve from 13 March – 30 June 2024.

Feature image: Soufiane Ababri, Bedwork, 2023. Between two paragraphs of Oscar Wilde’s reading. © Soufiane Ababri. Photo: Rebecca Fanuele