Behind the Biennale: Archie Moore Centres Aboriginal Narratives at the Australia Pavilion

By Ellie ButtroseAhead of the 60th Venice Biennale — open to the public from 20 April 2024 — Something Curated continues its new series, Behind the Biennale. Comprising a collection of short essays from the curators of select national pavilions, the series offers first-hand perspectives on some of this year’s most anticipated presentations. Following Danish curator Louise Wolthers’ piece, the curator of 2024’s Australia pavilion, Ellie Buttrose, shares her insights on working with artist Archie Moore.

Archie Moore is an artist I have long esteemed. His aesthetically refined and politically incisive artworks engage audiences on an emotional level. Archie and I recently worked together for the exhibition ‘Embodied Knowledge’ that I co-curated with Katina Davidson at the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art in Brisbane, Australia. The public art museum is situated alongside a river. In place of water views, architect Robin Gibson designed a pond to run through the centre of the brutalist concrete building. It is here that Archie created Inert State, 2022. The installation comprises 200 coronial inquests into First Nations deaths in custody, floating in the water.

The audience catches glimpses of themselves reflected in the water as they view these bureaucratic documents that discuss the curtailment of the lives of children, parents, cousins, and grandparents. Inert State points to the hollow words and lack of action in addressing the underlying causes – poor access to health, education, and housing – for Indigenous Australians, being one of the most incarcerated people globally. The success of this artwork is the way that Archie was able to take statistics repeated in news reports and make them tangible for audiences. While the artist specifically addressed the lived experience of Indigenous peoples in Australia, his artwork resonates with carceral justice initiatives worldwide.

When Katina and I first asked Archie to propose an artwork he was clear about the concept for Inert State but the practicalities of how to float stacks of paper in moving water – no easy feat – was a collaborative effort. QAGOMA is the home of ‘The Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art’, and so the onsite team of curators, exhibition designers, conservators, carpenters, metalsmiths, and installers have decades of experience helping artists realise new artworks. The exhibition designer Melissa Gore and sculpture conservator Elizabeth Thompson, along with the wider workshop and installation team, were instrumental in materialising Archie’s vision through a mix of hidden floating devices and weights.

For the Venice Biennale, it is standard for artworks to be made in advance and shipped to the Australia Pavilion. kith and kin is the first timethat an artwork will be realised onsite. Archie and I are thrilled that architect and BVN Principal Kevin O’Brien has come on board as the design consultant for the exhibition. We are working with Kevin to plan subtle elements that affect the pace and orientation of how audiences will navigate the exhibition – slowing them down to contemplate Archie’s project, which is a hard task when biennale visitors are consuming art at a feverish pace.

Kevin and Archie have worked together a couple of times before. Once for A Home Away From Home (Bennelong/Vera’s Hut), 2016 for the Biennale of Sydney, recreating a house built by British Captain Arthur Phillip (1738–1814) for Woollarawarre Bennelong (1764–1813), a Wangul man of the Eora nation who had been kidnapped by Governor Phillip but went on to become a key diplomat between the British and Indigenous Australians in the early days of the colony. Archie and Kevin designed the single-room structure from written descriptions in colonial archives but lowered the height of the door so that audiences take a humble position as they enter. As visitors walk into the brick building, they are surrounded by rusty corrugated iron walls and a dirt floor. The interior is a recreation of Archie’s memory of his grandmother’s shack. Lack of access to adequate housing continues to be a systemic problem that is faced by First Nations peoples in Australia.

As people exit the meagre dwelling, they are surrounded by magnificent views of Sydney Harbour which includes some of the most expensive real estate in one of the world’s richest countries. In A Home Away From Home, the artist places contemporary wealth disparity into stark relief. This artwork also reflects how Archie brings the wider site into play within his artworks. In Venice, the Australia Pavilion is situated along a canal but the large window has always been closed during art exhibitions. For kith and kin, we are ensuring that audiences will have a view of the water. This is to reiterate that the canal is connected to the sea, which is joined to all the world’s oceans – including the waterways of Australia. Emphasising the relationship between waterways is a way to reflect how everything on the planet is connected. In Archie’s description of the exhibition title, kith and kin, kinship is not limited to humans; it binds people to plants, animals, landforms and waterways throughout the ages.

Archie often refers to his lineage in his art and kith and kin will draw upon his interest in familial history. The artist has been scanning libraries, newspapers, cadastral maps, pastoral diaries, vernacular archives, historical societies, state archives, the genealogy website Ancestry, and speaking with family members in person and via social media to find references to kin. It has been an honour to hear Archie share his family stories during our preparations for the 2024 Venice Biennale. Archie foregrounds that his Kamilaroi and Bigambul oral history reaches back 65,000+ years while the written archive only dates back some 250 years to British invasion – his family history is also the story of the Australian continent and more recently the nation.

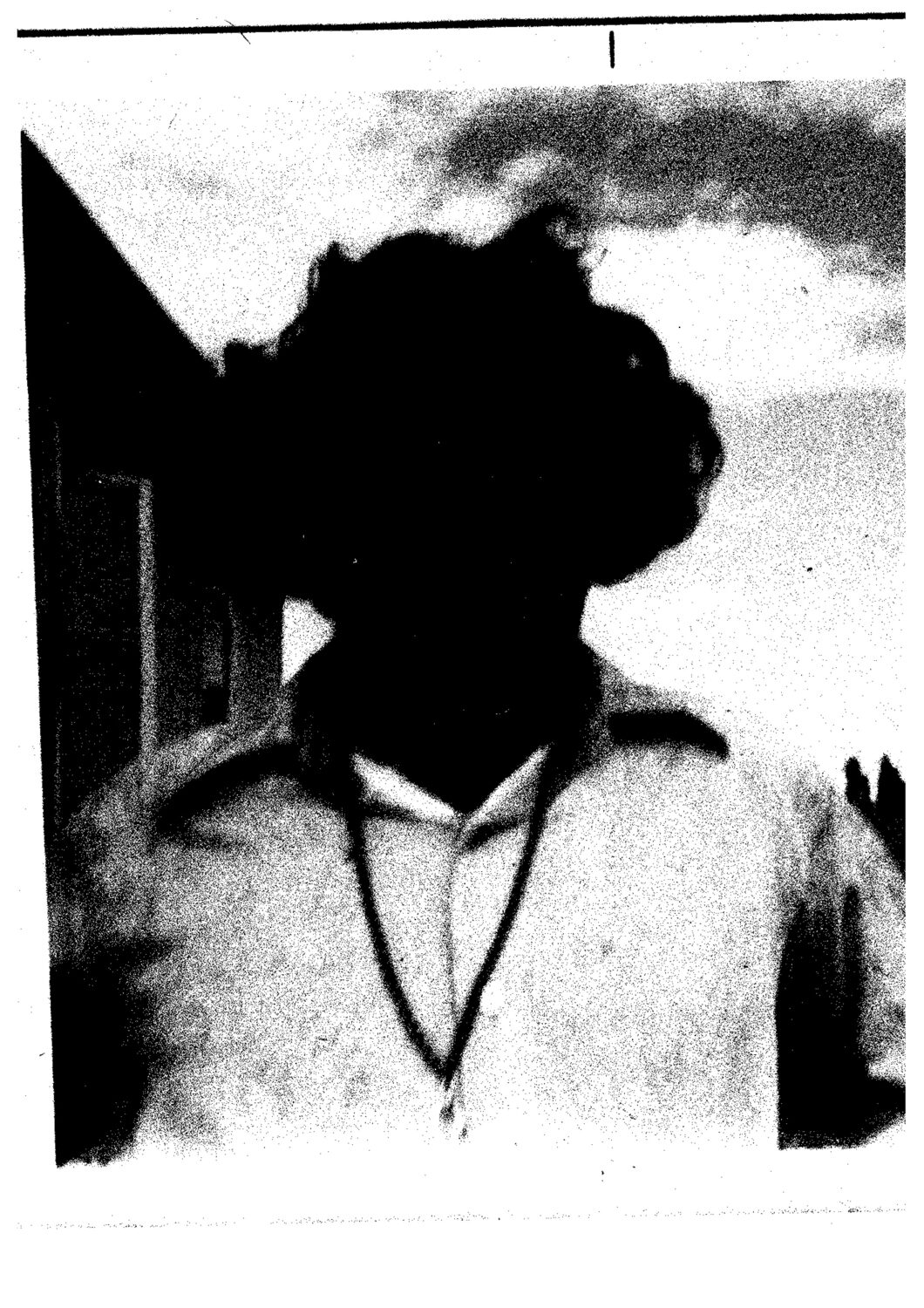

While undertaking research on Kamilaroi and Bigambul histories and his family members, Archie has often come up against dead ends – state departmental material is at times redacted, the church did not reply to requests, under-resourced archives are difficult to access, other documents have been wilfully destroyed, and on some occasions individuals have taken their knowledge to the grave. Archie uses visual, spatial and conceptual voids in his artworks to reflect these gaps found in the archive. A key kith and kin image that articulates this approach is a photocopy of a photograph of Archie’s uncle, Fredrick Noel Clevens.

The picture is just a black silhouette as visual information of Fredrick’s features was lost in the reproduction process. Discussing the importance of the picture the artist states: ‘I see this degraded image as a metaphor for the ever-changing effect of retelling of memories and events.’ Moreover, he notes that in the Kamilaroi astronomy, the ancestors reside in the dark patches of sky between the stars. Thus, Archie’s artworks are a cue that darkness, voids, and abstraction do not necessarily signal the absence of life.

Feature image: Archie Moore, Valerie Jean Moore and William Clevin in kith and kin, 2024. Found photograph, Australia Pavilion, Venice Biennale 2024. Graphic design work: Žiga Testen and Stuart Geddes. Courtesy the Artist and The Commercial. © Archie Moore