What Is Zenga?

By Tiffany LambertRecent years have seen essential work being done to reframe and rearticulate narratives of art history that are more nuanced, layered, and intersectional. We have witnessed ever more vital considerations that reckon with periods of erasure and artists’ work that has previously been unheeded, even as it revises our thinking of mainstream movements including Art Nouveau, Minimalism, and Conceptualism. Such critical activity refreshes ideas of the stagnant status quo, richly complicating and relocating some of the origins of art historical movements and artistic practices across geographical and ideological boundaries.

The cross-pollination between Japan and Europe dates back to the 1600s when Japan and the Netherlands regularly traded through the Dutch East India Company. In 1853, the American Commodore Matthew C. Perry’s squadron of navy ships arrived in Edo Bay, forcing a treaty with the U.S. that granted access to a country that had remained strictly closed (sakoku) to foreign nations for over 200 years prior. The late 19th century saw Japonisme, the French interpretation of Japanese aesthetics and the idea that utilitarian objects — dishware, vases, baskets — were works of art.

Numerous figures and prominent groups related to 20th century strands of Modernism — progenitors of Art Nouveau, Art Deco, the German Werkbund, and the Bauhaus, among others — were all familiar with Japanese ideals in art. (Many even spent time in Japan themselves.) These facts underscore the active circulation of ideas back and forth between Japan, Europe, and the United States that would come to radically transform global visual culture.

It was not only the objects, crafts, and arts of Japan that appealed to Europeans and Americans. Japanese and East Asian religion was also highly fascinating and, ultimately, influential on art. Zen Buddhism, which arrived in Japan in the late 12th century, spread heavily in Euro-America after 1893 when Shaku Sōen (1860–1919) delivered the first English lecture on Zen in the United States at the World’s Parliament of Religions held in Chicago. Essential Zen texts were soon translated into English. D.T. Suzuki, a student of Sōen, famously helped to formulate what Zen meant in the West, including through his popular lectures on Zen in the 1950s at Columbia University where his audience included artists such as John Cage, Philip Guston, Betty Parsons, Ad Reinhardt, and Mark Tobey.

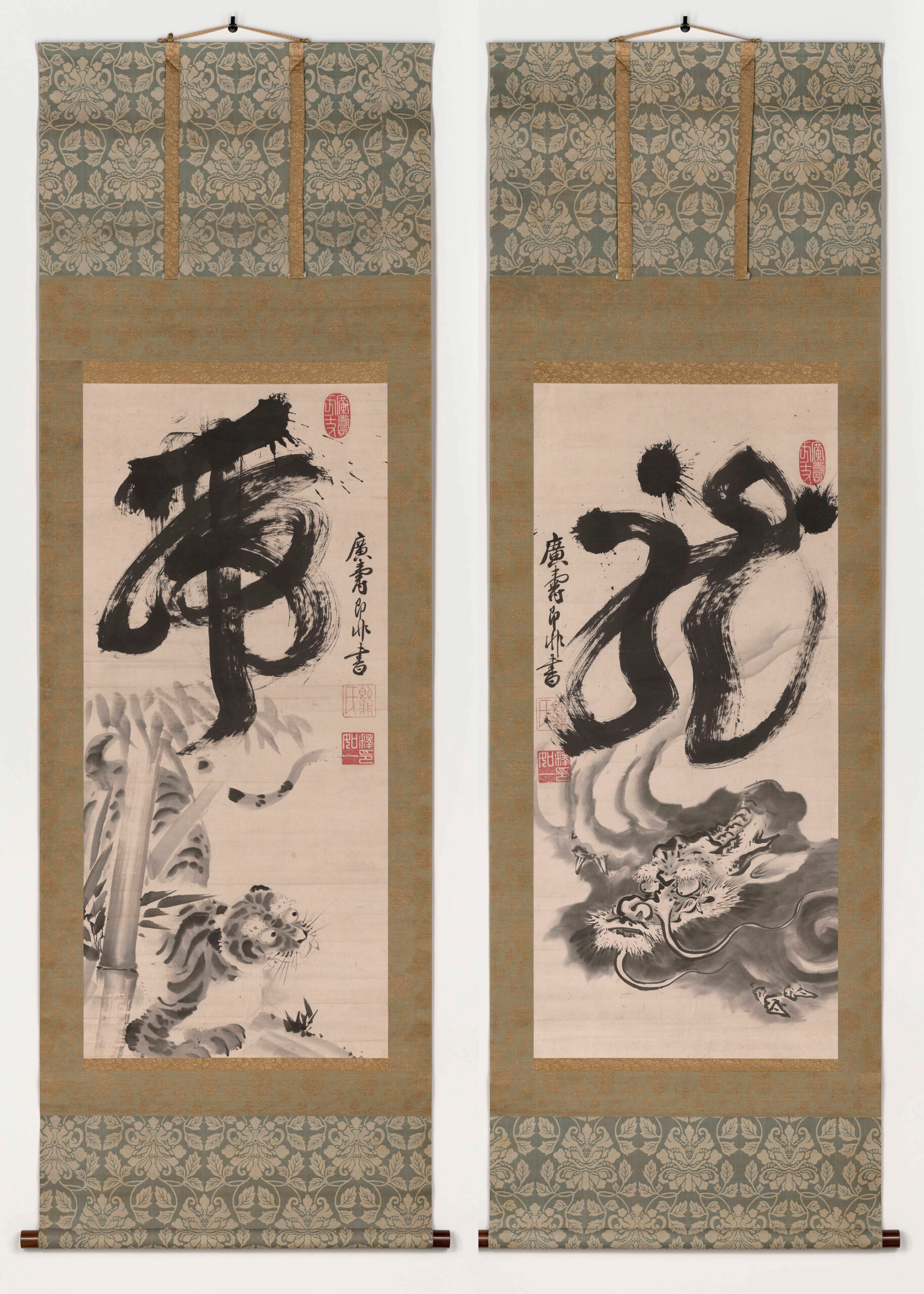

Zenga, or Zen paintings in Japanese, proves another important lens with which to consider art history, particularly American art after the 1950s and 1960s. Ink paintings and calligraphies created by Zen Buddhist monks from the Edo period (1615–1868) into the 20th century, Zenga had particular appeal with 20th century artists, including Abstract Expressionists, who were struck by Zenga’s gestural, direct, and improvisational aesthetic qualities.

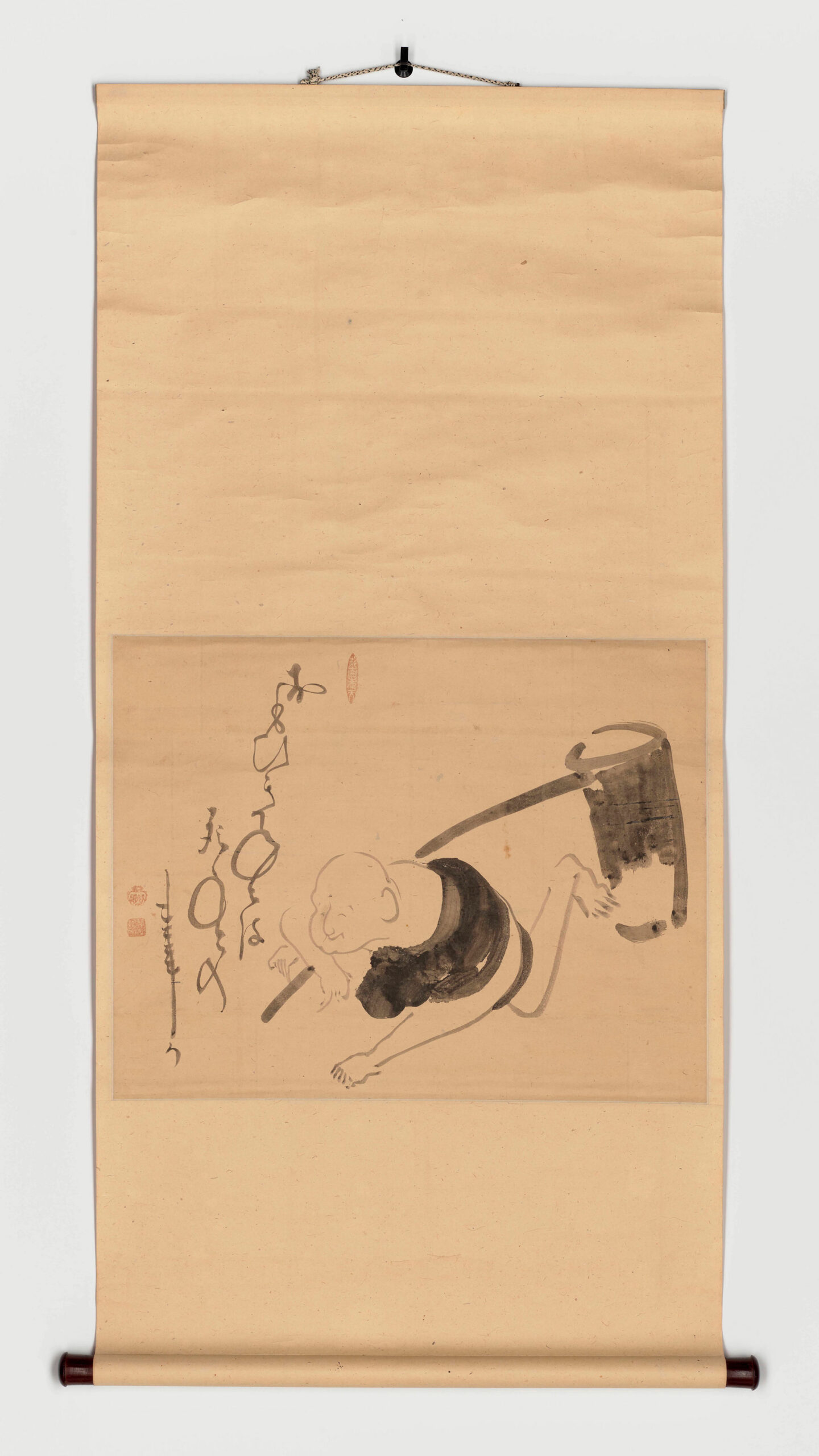

While Zenga have been cultivated into art in our contemporary understanding, in their own time they generally were not described nor intended as artworks. Instead, they were made by monks as a part of their teaching activity and often included inscriptions of Zen expressions. The most notable monk-painter to originate Zenga as a canon was Hakuin Ekaku (1685–1768) who was notable for his reform of the Rinzai School of Zen Buddhism, his popularity, and his reach to a wide variety of groups — from other monks, the samurai class, to everyday people including rural farmers and merchants. Hakuin, who began painting quite late in life, after his 40s and even more so into his 60s and 80s, greatly expanded the thematic scope of traditional Zenga to include themes that would appeal more broadly to the masses, folk deities, ubiquitous objects (such as a stone mill and the monk’s fly whisk), and Confucian sayings.

Where Hakuin did incorporate popular traditional subjects from the Zen canon, including Zen patriarchs and eccentrics, he is known to have exaggerated their features or to have depicted them in unconventional scenarios. For example, Hotei, the wandering, portly Chinese Zen priest who was dressed as a vagabond carrying his possessions in a burlap sack, is traditionally represented as either sleeping, pointing at the moon, laughing, or playing with children. In Hakuin’s hands, Hotei can be seen sprinting and with a rice-pounding mallet rather than his sack, mobilizing a secular figure as a common citizen.

Altogether, Hakuin created roughly 10,000 works in his lifetime. Despite Hakuin’s reach and successes with ink paintings and calligraphies during his own time, it is only in the postwar period that Zenga became identified and understood as an artistic genre. The term Zenga itself was not conceived until 1959 by the German Kurt Brasch (1907–1974). Between 1959–1965 there were a staggering 24 exhibitions alone that were dedicated to Zenga in Europe.

None Whatsoever: Zen Paintings from the Gitter-Yelen Collection, on view now through June 16, 2024 at Japan Society in New York, is an exhibition presenting 50 Zenga from the 1600s into the 20th century. The exhibition presents Hakuin’s works alongside Zen monk-painters who came before as well as followers of Hakuin in order to demonstrate the formation and emergence of Zenga as an artistic canon in the 20th century and today.

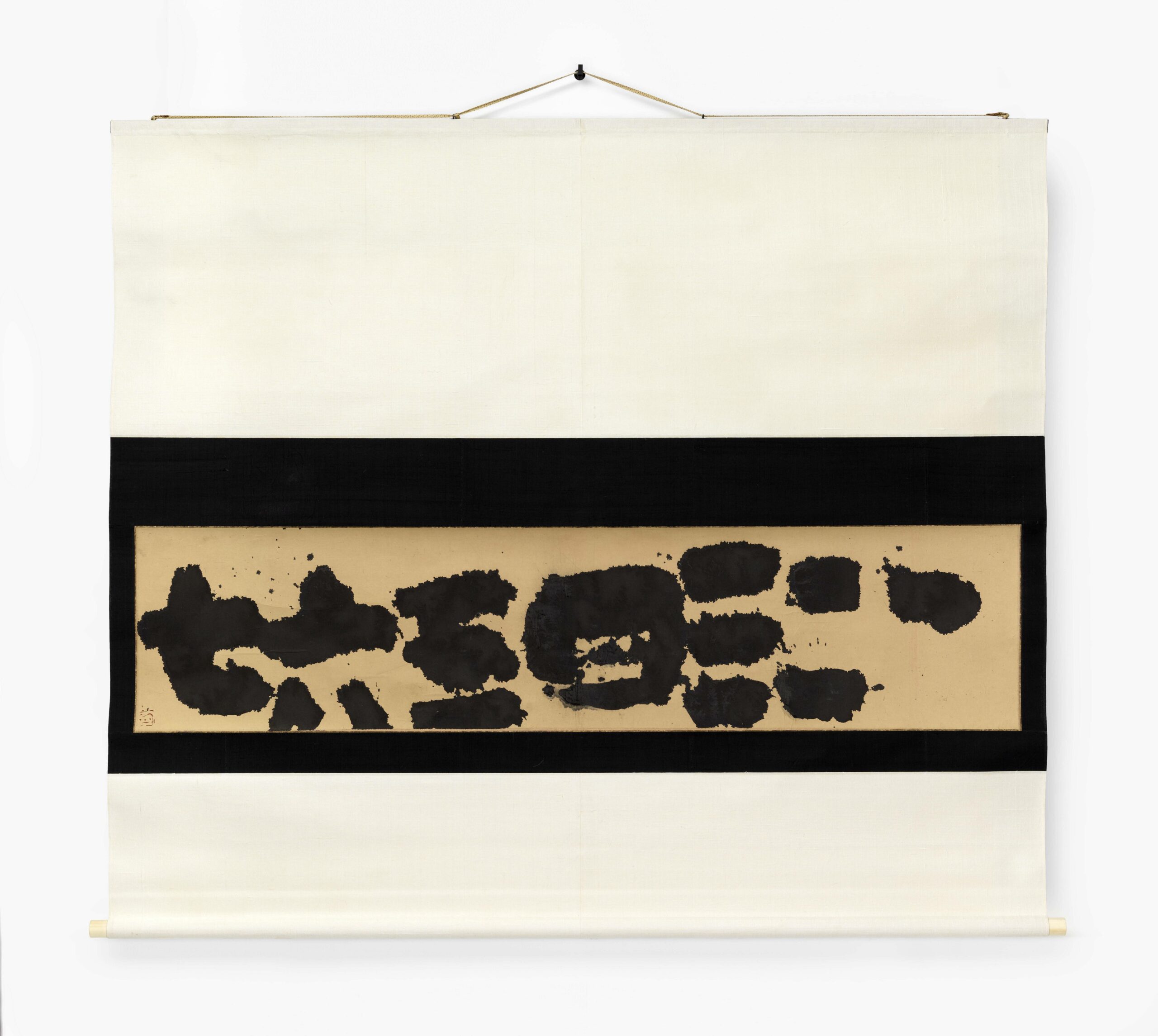

Through rare and important works from the renowned Gitter-Yelen Collection — including a full view of the over-20-foot-long scroll by Sengai Gibon, the only known scroll by the monk-painter to exist — the exhibition traces the visual qualities of Zenga and, through them, displays significant Zen Buddhist concepts. These include the Zen koan — paradoxical statements or unanswerable questions such as Hakuin’s What is the sound of one hand clapping? — the idea that enlightenment can happen in an instant and at any moment, and an emphasis on meditation.

Such undertones of Zen Buddhist ideology as illustrated in the works on view suggest an unmediated, liberated approach to artmaking that can be witnessed even today. Monk-painters of the Edo period, Hakuin Ekaku in particular, often worked fast and fearlessly, changing styles — from the figural to the highly reductive to the bold calligraphies of his later paintings — and subject matter at will. Similarly, the exhibition reveals little-known precedents for seemingly Euro-American-centric developments. Look close enough and it is not hard to see resonances to Minimalism or Happenings. Zenga makes important contributions to the conversation, limning complexities of the art historical canon that enliven untidy associations across disciplines, time periods, and cultures.

Tiffany Lambert is a curator, editor, educator, and writer. She is currently the Curator of Japan Society Gallery in New York and teaches at the Rhode Island School of Design.

With thanks to Dr. Yukio Lippit and Dr. Bradley M. Bailey, co-curators of None Whatsoever for their scholarship and insights.

Feature image: Hakuin Ekaku (1685–1768), Seven Gods of Good Fortune, 18th century. The Gitter-Yelen Collection: Kurt A. Gitter, M.D. and Alice Yelen Gitter