Sofía Salazar Rosales: “My Anthropomorphic Sculptures Keep in Their Mouths the Flavour of Their Origins”

By Keshav AnandExploring the fantasmas — ghosts, memories and echoes — that exist imperceptibly in the spaces we inhabit, Sofía Salazar Rosales’ practice draws from the languages of sculpture, installation and architecture, asking the question, “What if walls could talk?” Traversing various mediums, her works eschew categorisation, extending and unravelling unseen and unsung details of the world around us.

Hailing from Ecuador, the artist lives and works between Amsterdam, Quito, and Paris, and is currently undertaking a residency at De Atelier. Her first solo show in the UK, titled Yo no sé si tenga amor la eternidad, Pero allá, tal como aquí, En la boca llevarás, Sabor a mí, is now open at London gallery Alice Amati, running until 25 May 2024. To learn more about her practice and the new exhibition, Something Curated spoke with Salazar Rosales.

Keshav Anand: Can you give us some insight into your background — how did your interest in art first emerge?

Sofía Salazar Rosales: I lived in Quito, Ecuador, until I was 18 years old. My father is Cuban, but like many Cubans, he has not lived there for many years, although he returns often. My mother is a painter – she studied in Ecuador and China. From pregnancy until now I have been part of her work. I remember a bracelet we made with papier mâché, when I was little. I found it impressive that the cardboard of an egg carton can become something so solid.

The properties of materials have always fascinated me, their possibilities. I also remember when I started making little paper buildings and bridges. My mom would put them on a shelf that had glass doors. They became valuable objects that you could see in a vitrine. I suppose it was there that my interest in art emerged – building worlds, environments from accessible and light materials.

KA: How have you approached creating and selecting the works to include in your show at Alice Amati?

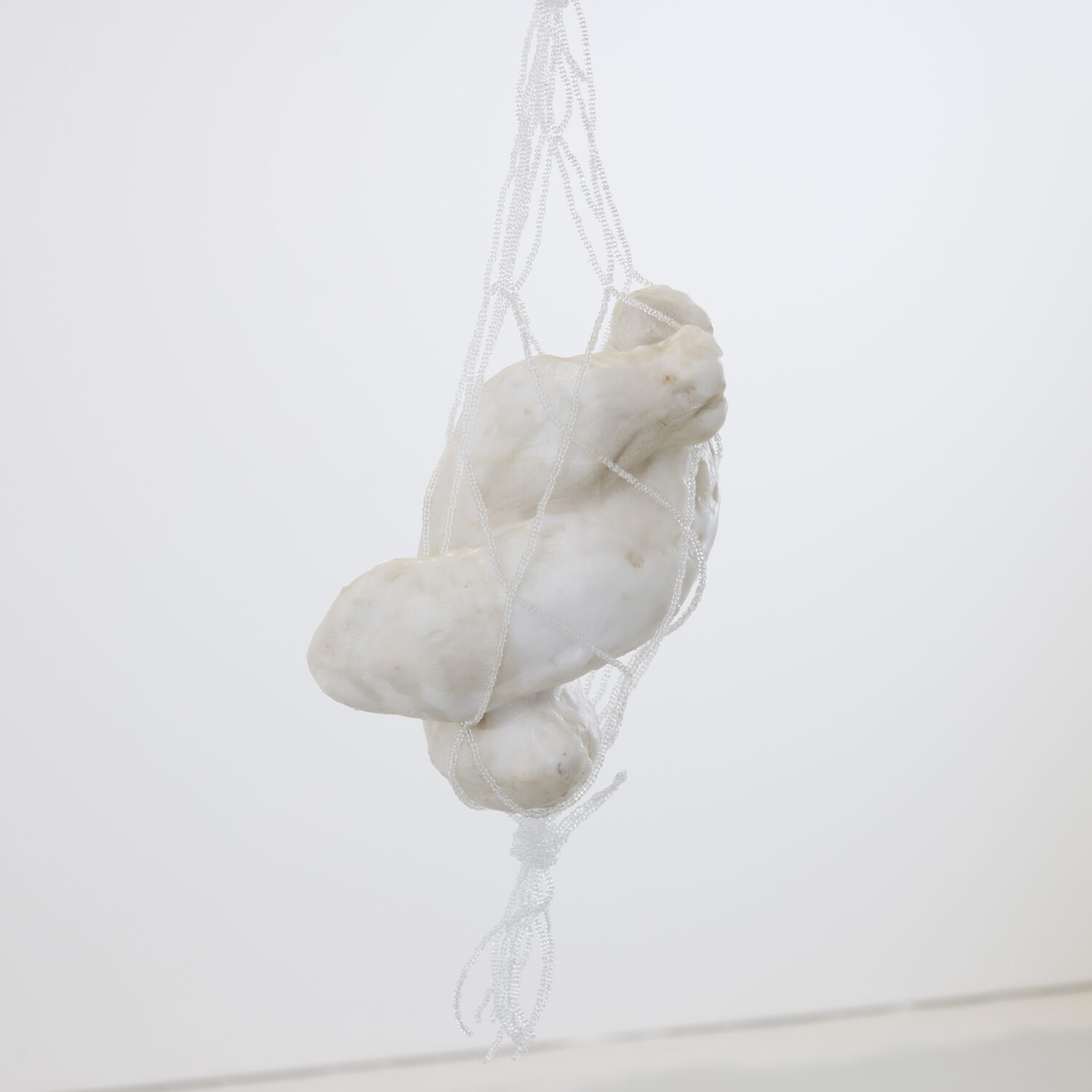

SSR: All the sculptures are continuities of a series of pieces that are part of the same installation that I have been building for about five years: There are bodies tired from the journey seeking to root. The pieces presented were created specifically for this exhibition, revisiting sculptures that materialise conversations between the artisanal and the industrial – for example, They ask to stay (Ghosts),where representations of bananas hug each other inside a mesh of woven glass beads that are normally plastic and standard in form.

Or in What hides the city in a hug? (Ghost), each teardrop pattern of the “metal” plate is cut one by one in cardboard. And the only mat in the exhibition is a reproduction of a hand-woven estera: the handmade gesture becomes reproducible and loses its aura through the cast. In the exhibition all the sculptures are identifiable objects but they have been represented, reproduced with other materials and specific gestures of construction so they can tell a story, often about displacement.

KA: What is the thinking behind the show’s title?

SSR: The title comes from a song: Sabor a mí by Álvaro Carrillo Alarcón. Using a fragment of this song came from a conversation I had with my romantic partner on a plane. I was telling him that I wanted the exhibition in London to be a weaving of ghost sculptures. That meant, I wanted there to be new pieces but that they represent series of sculptures that I have been building in the last few years.

I wanted them to appear in other forms, with different scales – ghosts of other sculptures. To which he responded with the synonym he found, “flavours,” and remembered the famous song by Carrillo Alarcón … After mutating, moving, my anthropomorphic sculptures keep in their mouths the flavour of their origins.

KA: Among other influences, your practice draws from languages of architecture — could you expand on this interest?

SSR: Growing up in Ecuador got me interested in construction. The mountains surrounding my childhood home were quarries. On my way from home to school I would pass through dusty roads, with cobblestones, asphalt and cement sidewalks. The drive lasted almost an hour, where it was nothing but successions of distant architectures, but above all, perpetual construction. Pure landscapes of formwork, of metal structures anxiously waiting for cement.

In my last years in Ecuador I lived in a republican house (that’s what we call certain patrimonial houses in the historic centre, the ones that precede the colonial houses). It is in adobe and its roof in carrizo, pre-Hispanic construction techniques. But its façade, reproduced, was inspired by Spanish architecture. In everyday life, the spaces that allow us to inhabit ooze displacements, yearnings for modernity, forgetfulness of local knowledge and its rescue.

In my work I am interested in architecture from different angles. I am interested in creating parallels between agro exportation and the way in which, according to the economic booms of certain products, cities and their constructions change. In a country like Ecuador, economic booms linked to agricultural crops have led to urgencies of “modernisation,” standardisation. Some examples are cocoa and reinforced concrete.

KA: What are some of your favourite cultural spaces in Quito?

SSR: In general, I find most of the cultural institutional spaces in Quito interesting. My favourites are the: MuNa (National Museum of Ecuador), the museum of pre-Columbian art Casa del Alabado and the Contemporary Art Center of Quito.

KA: And what are you currently reading?

SSR: I am currently reading Anne Dufourmantelle invite Jacques Derrida à répondre De l’hospitalité, published in 1997. It is part of my research for my next sculptures being shown at the Lyon Biennale.

Feature image: Installation view of Sofía Salazar Rosales: Yo no sé si tenga amor la eternidad, Pero allá, tal como aquí, En la boca llevarás, Sabor a mí, at Alice Amati, London, 2024. Courtesy of Alice Amati. Photo: Tom Carter