What Is Paleontology? By a Leading Paleontologist

By Alexander W. A. KellnerFossils stir people’s imaginations. Dinosaurs continue to be one of the main attractions of museums across the world, drawing crowds fascinated by these ancient creatures. Following a devastating fire that destroyed 85% of the collection of the Museu Nacional/UFRJ — the largest museum of natural history and anthropology in Brazil — the institution has recently received a major donation from the Pohl family, comprising over one thousand fossils, including several rare specimens of scientific importance.

Marking this momentous time in the Museum’s rebuilding, Paleontologist and Director of the Museu Nacional/UFRJ, Alexander W. A. Kellner has penned a short essay for Something Curated, offering an insightful glimpse into the evolving world of Paleontology.

What does this expression awaken in most people? A term that originates from the combination of the Greek words palaios (old), ontos (being) and logos (study), Paleontology is the science that deals with the research of fossils (from the Latin fossilis = obtained from the earth). Yes, most people will think of T. rex and other “monsters” of the past! Some were huge, others tiny; some had large teeth giving them a fierce appearance, others had no teeth at all; most had large tails and some had very large crests on their heads, while others had their bodies covered in scales or feathers.

They flew, swam and most lived and roamed the surface of the planet where, for a time, some became masters of the Earth. Yes, you must have guessed it! Here I’m talking about dinosaurs, flying reptiles and extinct marine lizards like mosasaurs. All these animals delight millions of people around the world, a fascination perpetuated by books, theme parks and films – some of which have become big box office hits in the entertainment industry.

But… Paleontology is much more than that. It is an exciting field of science that is changing a lot, becoming increasingly sophisticated…

As has been commonly reported, paleontologists, who are the scientists who study all the evidence of life preserved in rocks, are seen as people who spend most of their time in dusty fields, excavating fossils. I admit – there is something romantic about this. Camping in remote areas, living in tents, and being subject to and overcoming all weather conditions adds a very liberating and adventurous touch to our profession. But, in reality, experiencing such hazardous situations can be quite challenging and not romantic at all. Heavy rains, storms and – most annoyingly – the lack of appropriate spaces for the amenities we are accustomed to, such as scarcity of supplies and poor spaces for personal hygiene (forget about toilets and sinks!) are not for everyone. And I did not mention mosquitoes!

Furthermore, what has also contributed to the stereotype of a paleontologist’s work is the mistaken notion that we sit in our labs removing dust from bones that were collected in the field. Nothing could be further from the truth of this exciting and rapidly evolving scientific field. More and more scientists dealing with evidence of deep-time life are working with gloves on and in shiny laboratories, applying different technologies with sophisticated and expensive equipment, trying to obtain novel information about new and old specimens.

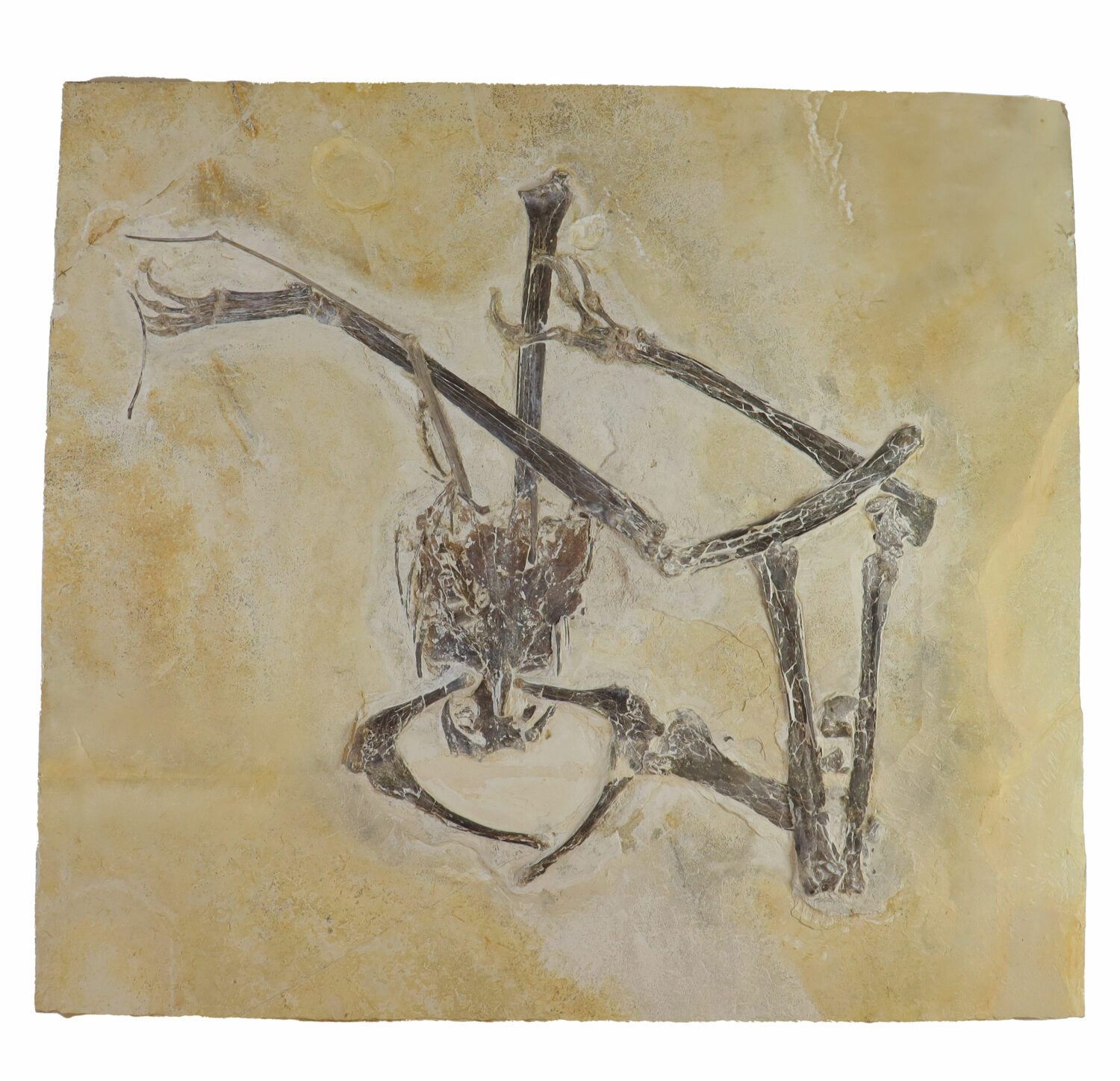

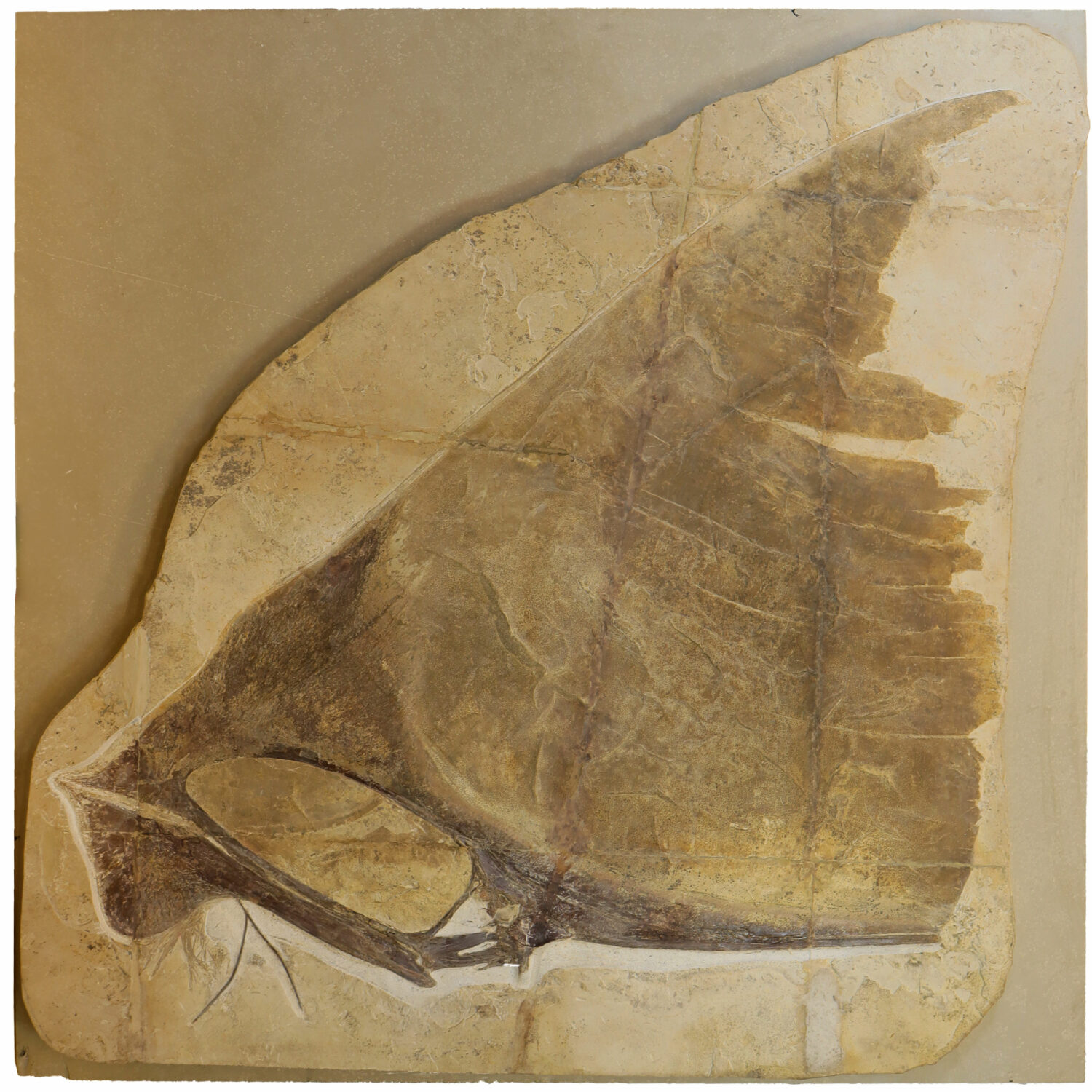

An important aspect that needs to be clarified: paleontology is not just about dinos. Although I must admit that they are the sexiest fossils in the business (although I myself prefer to study their flying cousins called pterosaurs), the fact is that paleontologists are very interested in understanding more and more about the way of life and various biological aspects of extinct organisms. We are also increasingly working to unravel the environments in which these creatures lived and the relationship between environmental changes and how these affected the evolution of living things in the past. After all, there are reasons why the biota is presently the way it is.

To do this, it is necessary to study a series of different organisms, which leads to some specializations. For example, no paleoenvironment can be correctly understood without knowledge of former vegetation, a line of study developed by paleobotanists. Due to the fragility of leaves and other plant materials, evidence of ancient vegetation can often only be obtained from fossilized pollen, which due to its small size falls into the category of microfossils, recovered in very different ways than tree logs, shells, bones and teeth. Micropaleontologists also deal with other (micro)fossils that allow them to establish the age of rocks in which organisms, including dinosaurs and others, are preserved. But that is not all.

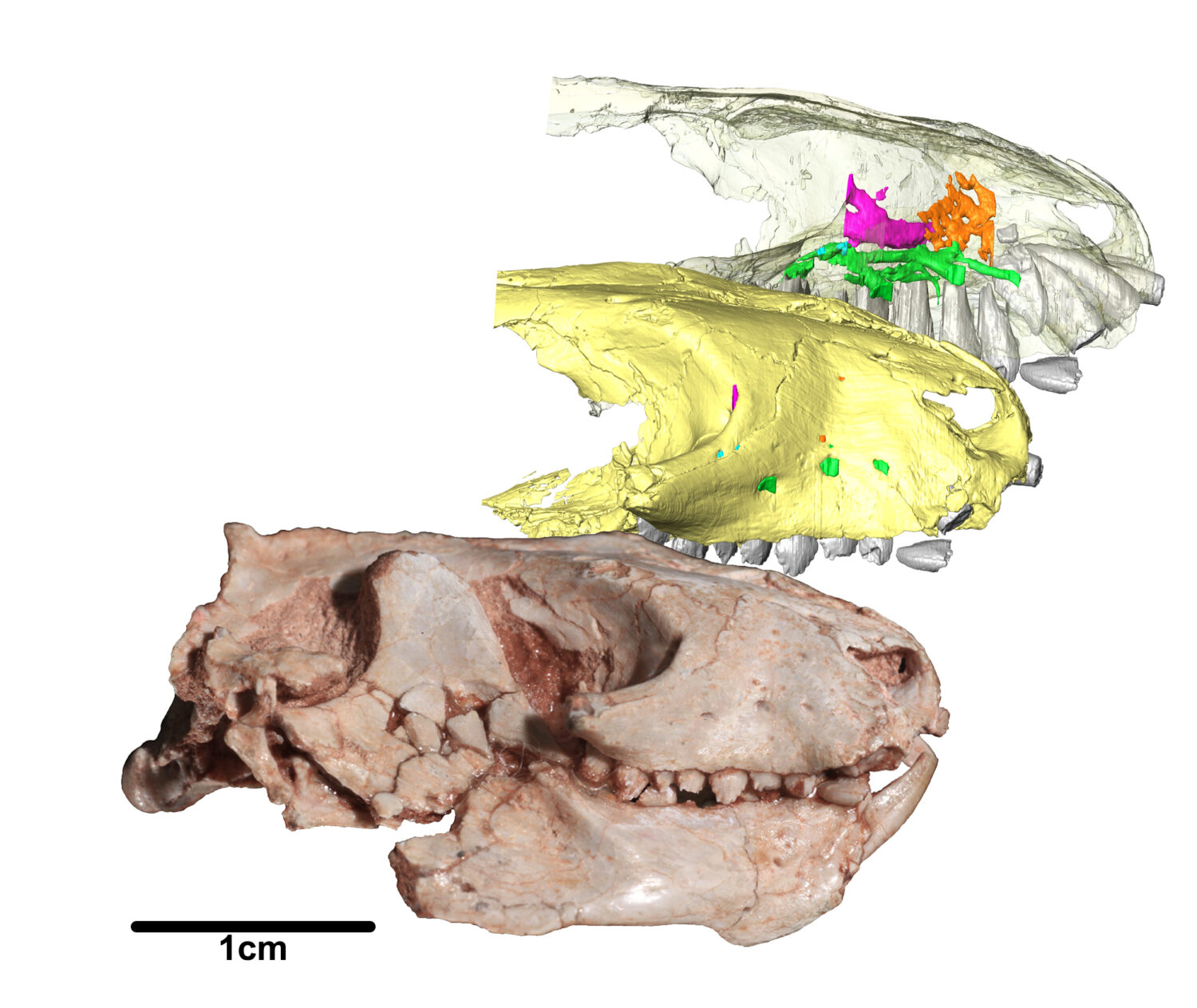

One of the main recent breakthroughs in paleontological research is the application of tomography. The tomograph, which is found in hospitals and has been very important for the health of human beings and pets, is sometimes also used to examine, let’s say, “more ancient” creatures. And there is microtomography, which is capable of obtaining even more detailed images of small specimens, which has become very useful for trying to understand what is “inside” of fossilized organisms. It cannot be emphasized enough that fossils are made up of minerals and not soft tissues like hearts and livers.

Among other applications of these techniques, paleontologists have managed to map the open spaces in the skulls, which gives us the opportunity to better understand some biological aspects of the animal under study, such as the size and organization of the brain, as well as sensory capabilities, including vision and olfactory systems.

Another field where scientists who study fossils have invested is paleohistology. As the name suggests, this technique consists of taking sections of the fossils and studying the microstructure to obtain valuable biological information, such as growth patterns and physiological aspects. This technique has been around for some time, but due to its destructive nature (no one likes slicing up their precious fossils…) it has prevented its widespread use. Now, with the discovery of more and more, often incomplete, paleontological material, there has been a gradual increase in paleohistological studies that allow us to provide new and relevant biological evidence for extinct organisms.

Back to the field activities that I myself really enjoy (besides Brazil, I have been to Antarctica, Iran, China, and many other places) – the techniques are not very different from those used by paleontologists in past centuries. Yes, we still have to go into the field to collect fossils by traveling dusty roads and camping in remote corners of the world. It is great to be able to see the remains of a creature that was buried for millions of years and be the first to see it. I simply love it.

One way or another, fossils fascinate everyone. We, at the Museu Nacional/UFRJ, who suffered a tragic fire in 2018, desperately need original material for our new exhibitions, which we hope to open in 2026. That is why we were so happy with the generous donation of more than 1000 fossils made by the Pohl Family. We are very grateful to Frances Reynolds, who made all the contacts and was instrumental in this important contribution to our Museum. The material includes rarities such as the skull of a flying reptile called Tupandactylus imperator, which will become one of the iconic specimens in the new exhibitions. This donation was made public on May 7th and we hope it will be followed by others.

Feature image: Photo by Handerson Oliveira. Courtesy Museu Nacional/UFRJ