Preview: Shanay Jhaveri on the Barbican’s Landmark Exhibition of Indian Art

By Shanay Jhaveri and Keshav AnandFrom 5 October 2024, the Barbican will host The Imaginary Institution of India: Art 1975-1998, the world’s first exhibition to explore and chart this period of significant cultural and political change in South Asia. Ahead of the exhibition, Something Curated sat down with Shanay Jhaveri, Head of Visual Arts at the Barbican, to learn more about the landmark show.

Jhaveri explains: “The Imaginary Institution of India surveys artistic production from across the Indian subcontinent during a 23-year period marked by social upheaval, economic instability and rapid urbanisation. The exhibition unfolds in a loosely chronological manner, framed by two significant national events in the history of independent India: the declaration of the Emergency in 1975, when democratic rights were suspended, and the nuclear tests of 1998, when the country relinquished its non-violent ideals to assert its place in a new global order.

The issues and concerns artists were responding to during this time such as government failure to uphold secularism, social justice, welfare, minority rights and affirmative action, are still very prevalent today not only in India but across the world. I take great solace in the work of these artists, and my hope is that by sharing their work through this exhibition, they will resonate with audiences and give them not only insights but also strategies and further resolve to navigate our fraught current moment.”

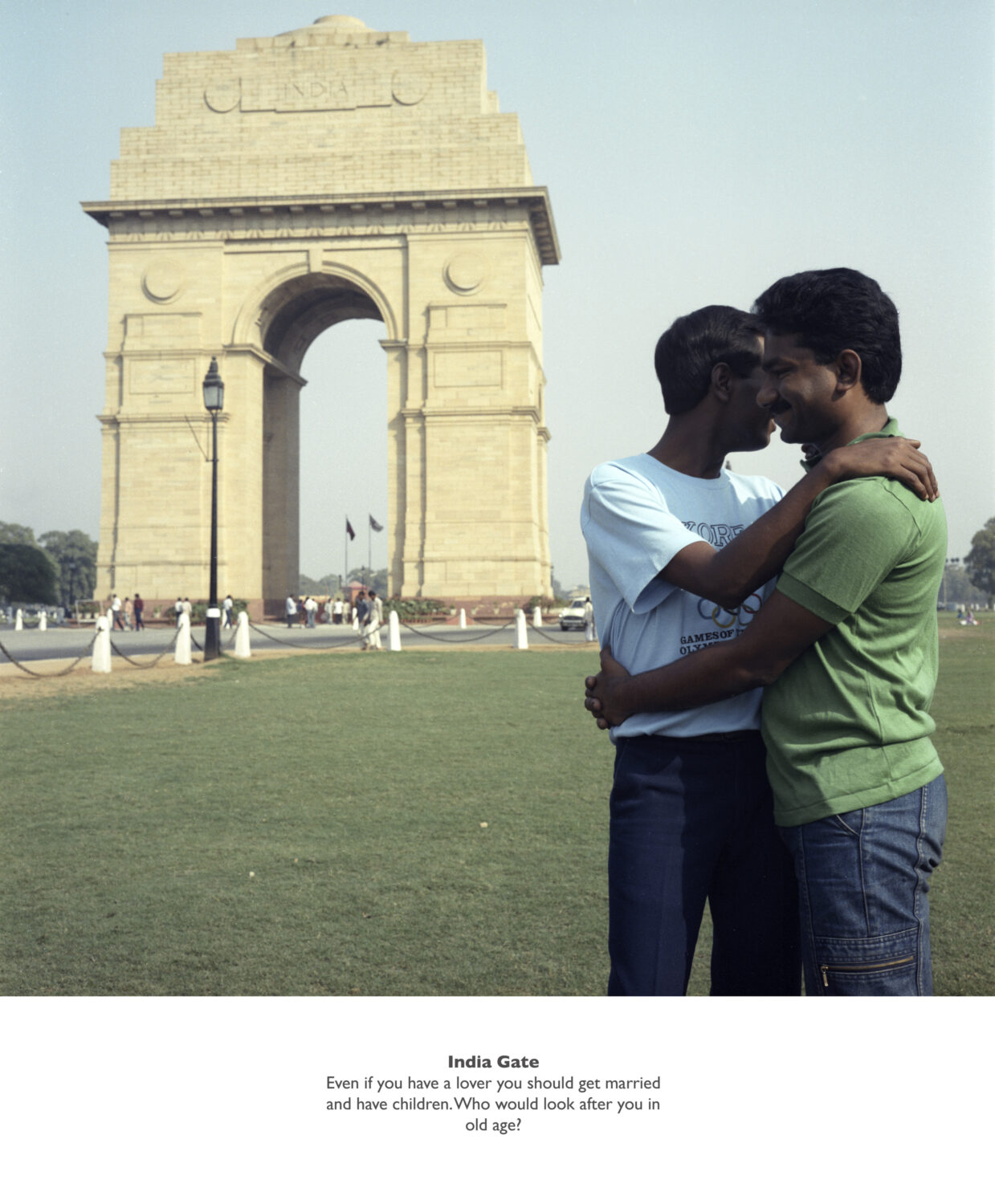

Works on show include Sunil Gupta’s photographic series Exiles, from 1987, which makes visible the lives of gay men in New Delhi in and around some of its most recognisable landmarks; Gieve Patel’s empathetic paintings which vividly portray daily life in the streets of India’s rapidly expanding, cosmopolitan cities in the 1980s; Meera Mukherjee’s intimately scaled and intricately detailed brones which, inspired by her time spent studying metal crafting traditions across India, use lost-wax casting techniques to address subjects both sacred and everyday; and a video installation by Nalini Malani in which moving image, projected on the walls and playing on monitors in tin trunks, considers the impact of India’s nuclear testing and links it to concerns around violence and forced displacement.

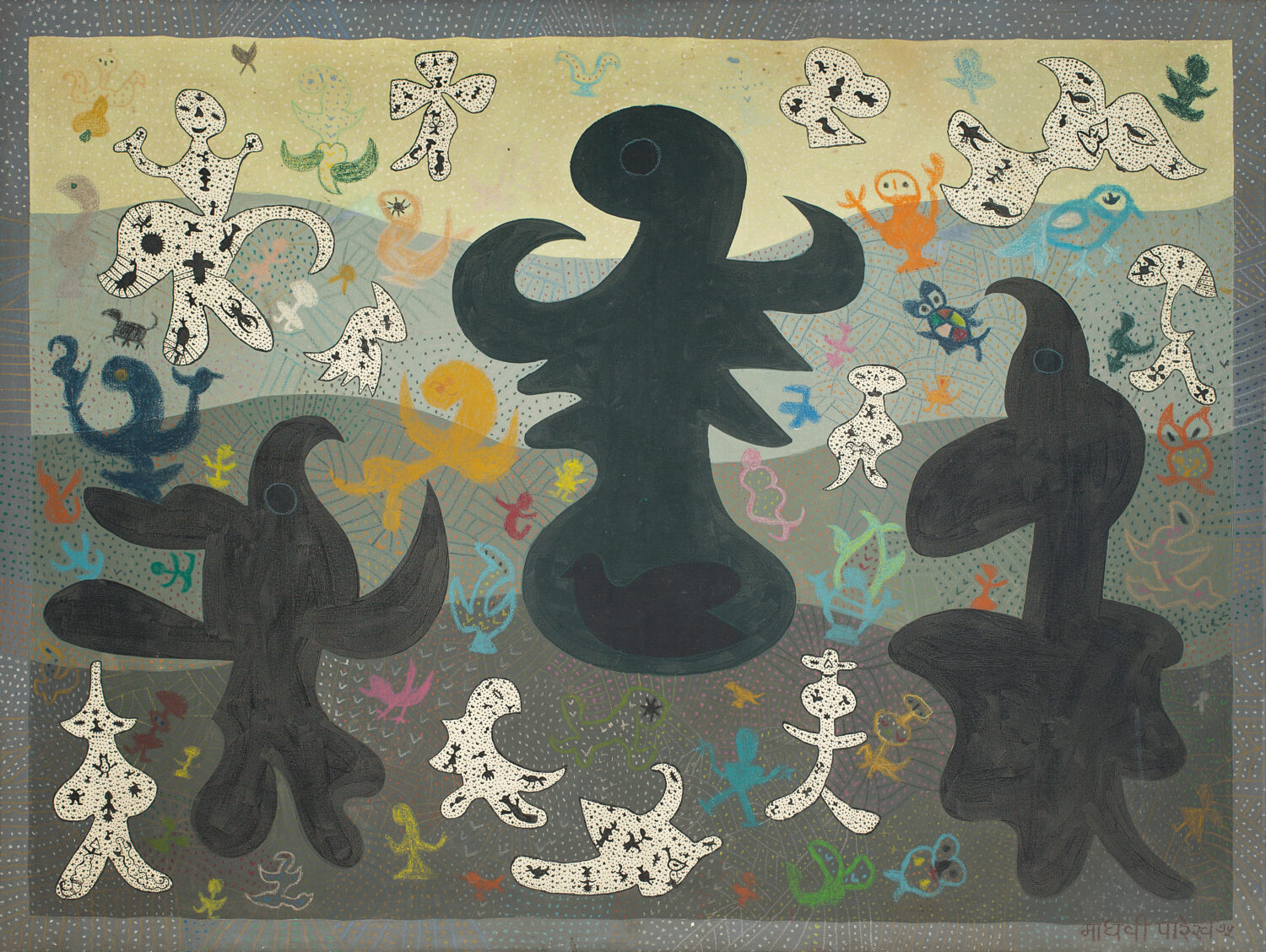

On the thinking behind the artists included, Jhaveri expands: “The exhibition features 30 artists, many of whom were friends, a second generation of post independent artists with shared aesthetic commitments and political allegiances. However, my endeavour has been to avoid re-treading and re-inscribing established hierarchies of recognition and importance. By not presenting works exclusively within established and received accounts, it may become possible to view and understand them as simultaneously partaking in a collective undertaking, and thereby resist detecting a binary or dualism in art-making, with one sort of representation dominant and the other subsidiary. The exhibition takes the Emergency as a starting point, exploring what it signalled and how it provoked the collective artistic imaginary, directly or indirectly. It surveys the artistic production that unfolded over the next two decades or so, within the turmoil of a changing socio-political landscape.

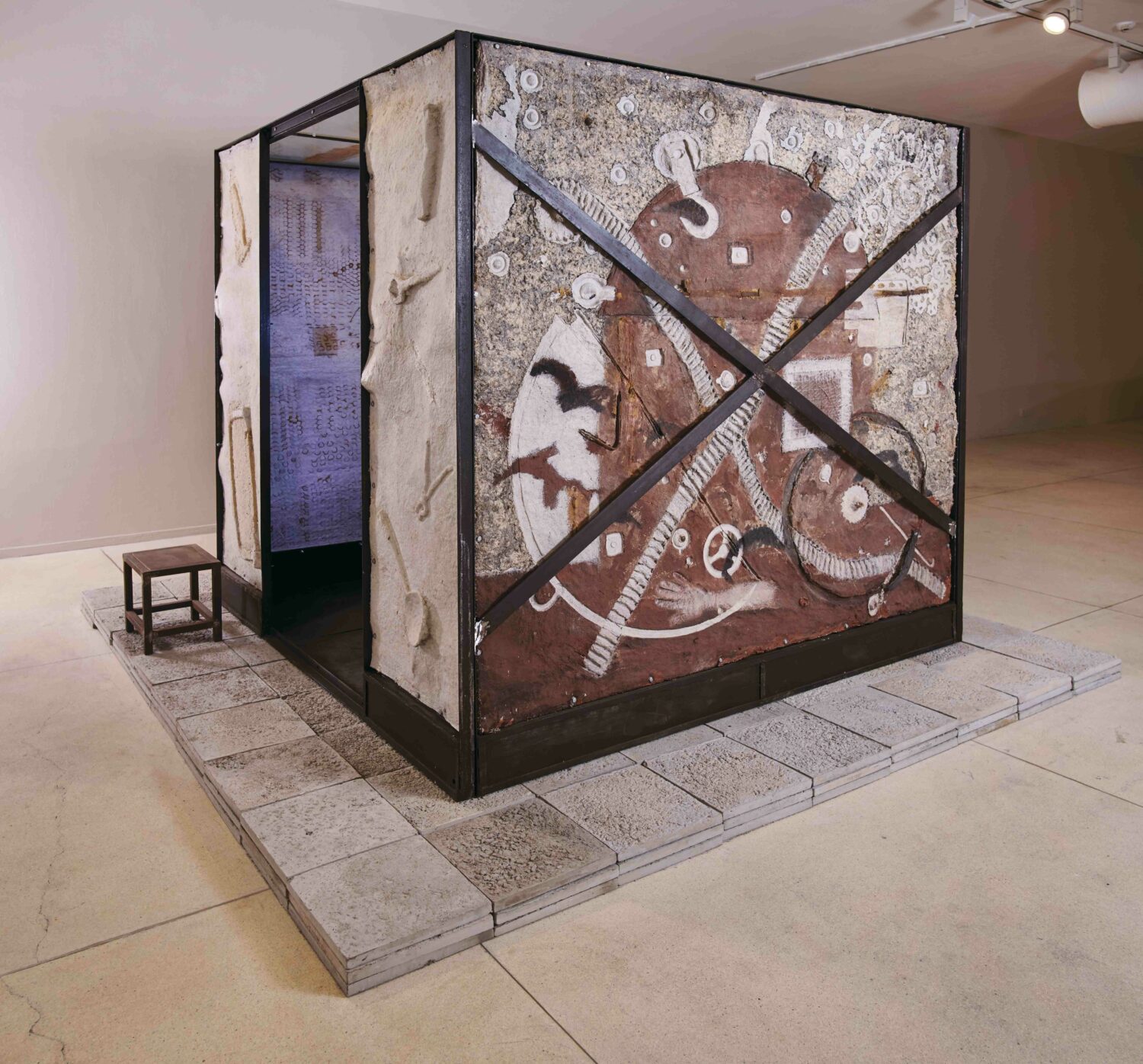

Some artists responded unequivocally in their works to the national events that they were living through, while others captured intimate and private moments. They not only made remarkable strides in representational painting, but some also developed their personal iconographies in other mediums including, importantly, installation in the 1990s. All of them combined social observation with individual expression and formal innovation to make work about friendship, love, desire, family, religion, violence, caste, community, and protest. This has determined the four axes that shape the exhibition: the rise of communal violence; gender and sexuality; urbanisation and shifting class structures; and a growing connection with indigenism.”

A specially curated film season, Rewriting the Rules: Pioneering Indian Cinema after 1970, will run alongside the exhibition. Jhaveri notes: “One of the great pleasures of being part of a multi-arts centre is to work with colleagues in other departments and have our programmes be in dialogue with one another. The concurrent film programme has been organised by my colleagues in the Cinema team Gali Gold and Tamara Anderson. They invited the guest curator Dr. Omar Ahmed who has described the 1970s to the 1990s as “decades when filmmakers rewrote the traditional rules of what constituted Indian cinema… Many also broke the rules when it came to aesthetic choices, opting for a creative hybridity and experimentation that fused together aspects of Indian art and culture with broader international styles.” The programme will also include a special evening of experimental film curated by She Heredia, the Founder and Festival Director of Experimenta.”

The Imaginary Institution of India: Art 1975-1998 will run at the Barbican Art Gallery from 5 October 2024 – 5 January 2025.

Feature image: Nalini Malani, Remembering Toba Tek Singh, 1998. Installation view, World Wide Video Festival, Amsterdam, 1998. © Nalini Malani