“Spitting Is a Dubious Act” — In Conversation with Tarek Lakhrissi

By Keshav AnandCombining poetry, film, sculpture and installation, French-Moroccan artist Tarek Lakhrissi’s transdisciplinary practice centres on queer and diasporic perspectives and experiences. His installations borrow their aesthetics from literature and pop culture, often using autofiction—the interfusion of a biographical report with fictional elements—to probe socio-political narratives. Inaugurating NıCOLETTı’s new London gallery space on 91 Paul Street, Lakhrissi’s latest solo show, SPIT, has been on view for the past month and remains open until 2 November 2024. To learn more about the exhibition, Lakhrissi’s practice, and his favourite places to eat in Paris, Something Curated’s Keshav Anand spoke with the artist.

Keshav Anand: SPIT explores tensions between violence and desire, which I understand was in part inspired by a personal experience at Pride in Paris. How did that incident influence your approach to creating this body of work?

Tarek Lakhrissi: Attending Pride in Paris was a pivotal moment for me, particularly regarding Gaza and the ongoing genocide, and the significant role social media plays in censorship, counter-narratives, and mobilisation. At Pride, carrying the Palestinian flag was my way of asserting visibility, especially within the demonstration crowd. The connection to desire, more specifically, relates to spit as an active element in sexual interactions. Interestingly, when someone spat on me, I wasn’t aroused—I was angry.

Desire, in this context, feels like something different, perhaps the opposite—public versus intimate, violence versus desire. When I spoke about spit as a starting point, especially in that scene at Pride, I couldn’t untangle all the images and symbols associated with spitting. It felt like I was talking and talking until the original topic nearly dissolved. I enjoy that transition between topics, ideas, and experiences—how materialities overlap. Spitting is a dubious act.

KA: How do literature and poetry help shape your visual language?

TL: My background is in literature and theatre, but I’m a self-taught artist who has developed a wide range of mediums. This diversity is intentional—I aim to ensure the longevity of my practice and avoid being confined to a single medium. Literature and poetry form their own worlds, and I’m deeply interested in transformative world-building within my work, which is filled with images, colours, and textures.

Lately, I’ve been incorporating more pop culture references, as they also shape both me and my work. In my creations, you might encounter Kaoutar Harchi, José Esteban Muñoz, Mahmoud Darwish, Félix González-Torres, Etel Adnan, or Monique Wittig, but you’ll also find Pokémon, Aaliyah, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Daria, RuPaul, or Lil Nas X. These layers and textures are essential to how I experiment with my visual language.

KA: Your glass sculptures evoke themes of desire and touch, but with an absence of contact. What is the thinking behind this intentional distance?

TL: The distance I’m referring to isn’t a literal one—it’s more about invoking layers and different textures. There’s the shiny car paint on the devil, something raw and fiery in the charcoal of the drawings, and the glass on the suns is bright and almost seductive—you feel tempted to lick the sculpture, but of course, you can’t, because of the behavioural expectations in a gallery. “Spit” is about saliva, that liquid in your mouth when you’re hungry or aroused, which also connects to violence and healing. Spit is so ambivalent, yet it gives me a sense of freedom—whether it’s spitting on something, kissing my partner in public, or using spit to heal a wound. It’s incredibly powerful.

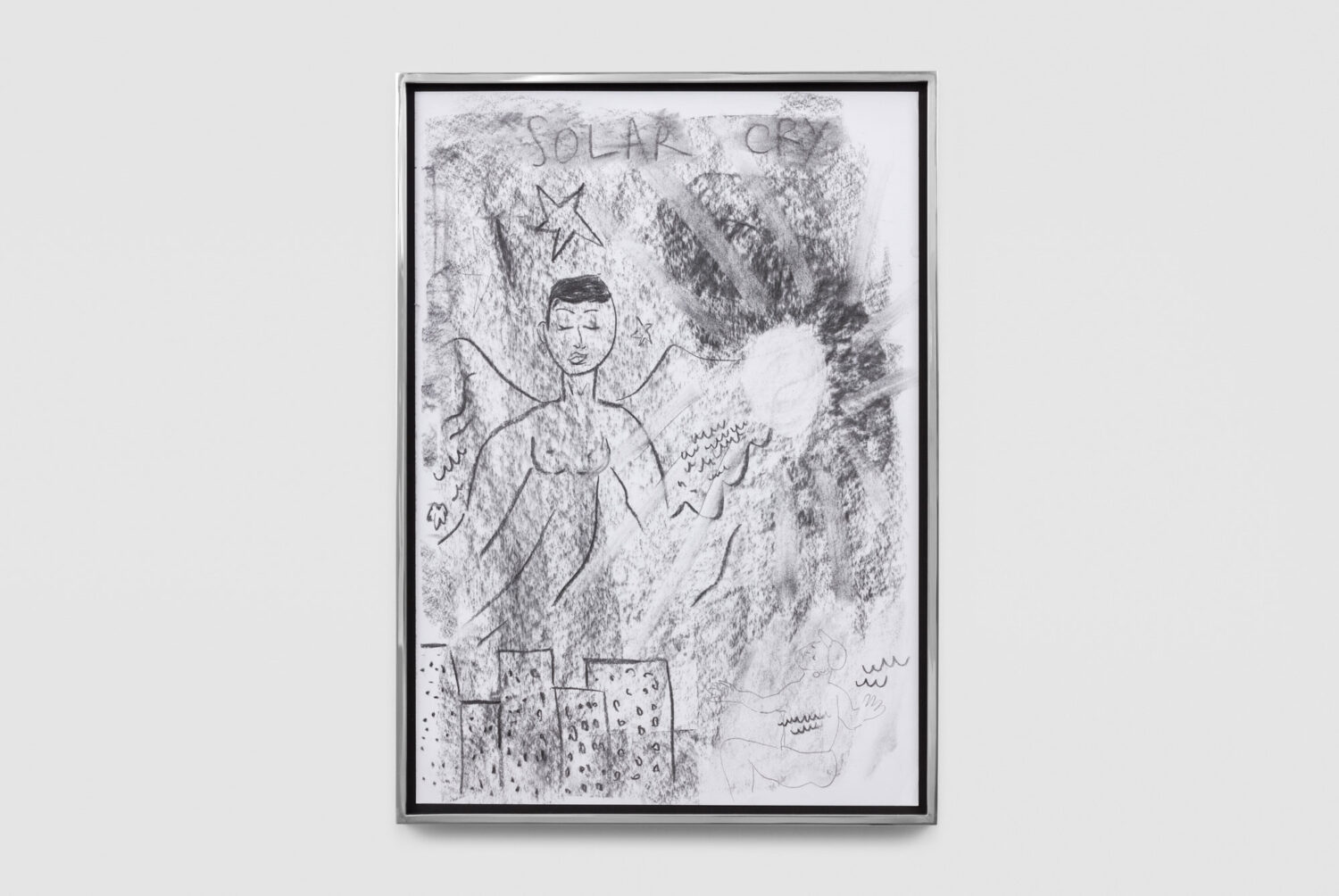

KA: In your drawings of alien and superhero-like characters, you explore transformations that are both painful and liberating. I’m curious to learn more about these works.

TL: These works are a way for me to reconnect with my drawing practice, something I once hid or felt ashamed of. I grew up drawing, but some people told me I should focus on more “masculine” activities, like basketball. Thanks to my partner, I’ve learned to let go of that shame and rediscover drawing as a daily joy. Now, I draw a lot—maybe even more than I write. I love combining the two, creating creatures from my imagination, using a “stream of consciousness” for words that emerge, becoming signals for the future or signs from the past.

I’ve learned to let myself go, becoming more independent in the process—it’s a raw space where I can be my true self. These angels and devils are now part of my emotional and creative landscape, along with references like Lil Nas X (again), Doja Cat, and Greek sculptures from the Louvre. I love mixing these kinds of inspirations. I also work with recurring symbols: stars, clouds, suns, flowers, teardrops—kind of naïve, emotional landscapes. They open my heart in so many ways.

KA: There is something very tongue in cheek about your larger-than-life sculptures like Angry Face With Horns — what role does humour, or perhaps irony, play in your practice?

TL: I often think of that sculpture of a laughing face, mocking visitors as they enter the gallery. Lately, much of my work has focused on the issue of access. I feel like art spaces—galleries and museums—can be very exclusive, especially for racialised individuals and those from working-class backgrounds. That’s my experience, where I come from, so I’ve always had a sense of ambivalence toward these spaces, even though I now work within them. I see these spaces as transitional, separated from the outside world—maybe because that world is collapsing.

So why not laugh about it? Party about it. Cry, pray about it. Everything in the art world feels transitional and transactional. Irony and playfulness are constants in my work—for example, the devil emoji, which one might send to a crush, is a way to connect and bring a different shiny materiality to the interaction with the viewer. The devil emoji now feels more draggy, queer, and ambiguous. Some people even see the Pokémon Gengar in this monster, and that’s exactly what it’s all about: pop culture, kinky narratives, and playfulness.

KA: To change pace for a moment, where are your favourite places to eat in Paris?

TL: I love this question! I’m always trying new places, so it’s hard to stick to just a few, especially since I eat out less these days. But I do have a soft spot for a good smash burger—Dumbo is my go-to. For brunch, I used to love Holy Belly. For a classic French restaurant, I head to Bouillon Julien or République, and for dinner, I enjoy La Taquinerie and for Italian food, I love Jones. When it comes to great wine and fine dining, Ellsworth near the Louvre is a favourite, which is owned by a good friend. My current favourite bakery is actually a Korean one called Mille et Un. As for Moroccan food, I usually wait to enjoy that with family when I visit them—because nothing beats a home-cooked meal!

KA: And what are you currently reading?

TL: Poor by Caleb Femi.

Feature image: Tarek Lakhrissi, SPIT, solo exhibition at NıCOLETTı, London, 2024. Photo: Jack Elliot Edwards