Infringes: 7 Artist Films Interrogating Documentary’s Conventions

By Komtouch NapattaloongAfter seven years of making documentary films, a colleague’s remark kept me up at night: “Documentary release forms,” they said, “have been linked to a lineage of control mechanisms found in American slave photographic history.” I was stunned—and soon learned about cases like Harvard’s claim over the images of Tamara Lanier’s ancestors, upheld by the American Constitution’s First Amendment. As filmmakers, we’re often told to view these legal documents as moral safeguards, yet this obscures a darker reality. Documentary release forms, for instance, supposedly aim to inform subjects of how their stories will be shared. Yet, as I mulled over new revelations, my suspicions grew: these documents disproportionately serve to protect filmmakers, broadcasters, and distributors, granting them authority over others’ names, images, and stories with a single stroke of a pen.

When the newly inaugurated Bangkok Kunsthalle invited me to curate a film programme, this awareness simmered at the back of my mind. Initially hesitant to curate a film programme again, I felt drawn to this new space: the Thai Wattana Panich building, a dark, storied structure once dedicated to publishing school textbooks. The power of institutionalised knowledge here felt almost palpable. An opportunity to explore questions of memory, power, and what we take for granted became apparent and in Thailand’s current cultural climate, where the once-resounding march movements of recent years have all but faded (some even co-opted by rainbow-washing campaigns), it all seemed ripe for a cinematic intervention. It is here where the concept of Infringes took shape as a way to challenge accepted narratives and power, drawing on seven artist films that interrogate both propagated mythologies and documentary’s own conventions while celebrating vibrant creative infringements.

Chulayarnnon Siriphol’s Birth of Golden Snail opens the programme, set against Krabi, Thailand a place rich with archaeological and folkloric significance. In this 16mm film, stripped of sound and colour, Siriphol plays on these significances, adding his own take as a counter-narrative that challenges official histories. When the film was banned from the Thailand Biennale Krabi 2018 under Prayut Chan-o-cha’s military regime, it highlighted the tension between art and authority. Citing concerns about “morality” and “national security,” the authorities removed it from Khao Khanab Nam cave, effectively stripping it of its intended context. The suppression perhaps stemmed not just from its nudity or sexual undertones, but from the film’s engagement with Thai popular literature, often authored by male elites. Now in a different sort of cave setting, the film calls attention to these power structures and popular works like Sang Thong (The Prince of the Golden Conch Shell) and Khu Kam, revered in the Thai literary canon, yet mask power dynamics, nationalism, excessive violences, and chauvinism. The question remains: who holds the power to define accepted morality, history, and stories?

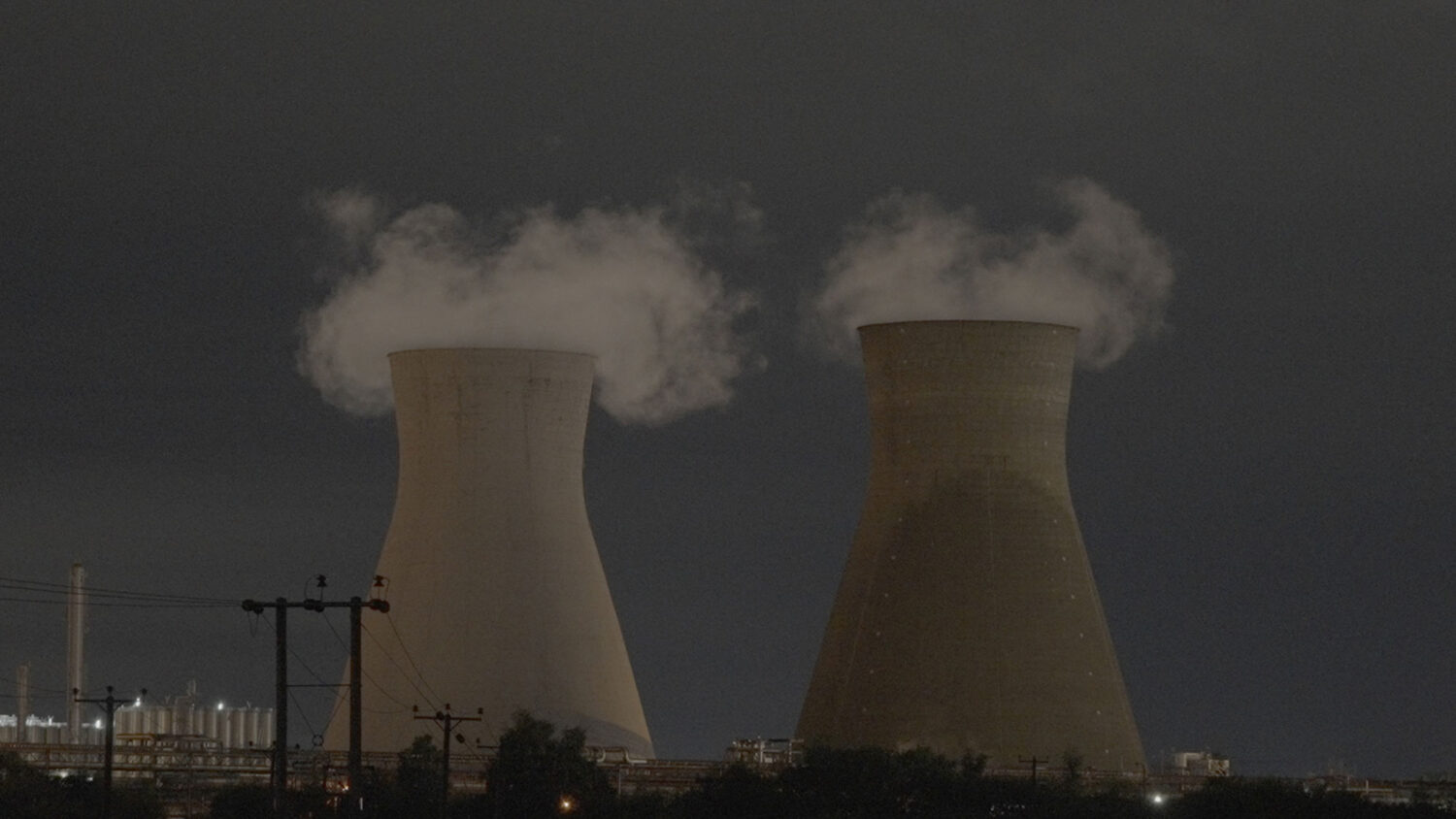

Aura Satz’s While Smoke Signals takes viewers to the industrial landscape of Grangemouth Oil Refinery in the UK, blending sirens, machinery hums, and a tone of premonition into a meditation on sound, warning, and primitive consumption. The film questions how modern sounds, such as sirens, fade into the background, losing their potency to warn and alert. While Smoke Signals mirrors the Thai Wattana Panich building’s role in the Infringes programme: this gallery, once a place for producing textbooks, is a site haunted by its past purpose of encoding knowledge for the state. The sirens and emissions of the refinery, like the textbooks here, stand as testaments to systems of control that we passively accept. Satz asks us to consider whether we truly “listen” to the narratives that surround us or if we have normalised them, becoming deaf to their impacts.

Jiří Žák’s Unfinished Love Letter subverts the documentary gaze by intertwining propaganda, history, and a fictive romance. Set against the backdrop of the Czech arms industry’s long-standing relationship with Syria, the film uses archival materials and mirage-like effects to conjure a retelling of this partnership. The mirage-like effect invites us to experience propaganda as “consensual hallucination,” where romantic language is applied to transactions steeped in power imbalances. More than an exposé on bilateral cooperation, Žák’s work critiques the Czech state’s betrayal of Syria, once embraced in economic partnership but later disregarded amid the Syrian crisis (2011-present). The film questions how narratives about nationhood are woven, often trading on public complicity and amnesia. By invoking a fictional love letter, Žák navigates ethical contradictions where weapons “even when not used, still work,” reminding us how often power dynamics hide in plain sight.

Moving to contemporary corporate hegemony, Riar Rizaldi’s Notes from Gog Magog immerses us in a world haunted by transnational corporate influence. Samsung is a corporation so omnipresent that it touches nearly every facet of life, from healthcare to consumer technology, while crushing labourers in its offices and ports. The film weaves the precarious lives of Indonesian port workers and Korean office workers into the narrative of capitalist violence, where corporations cross borders to continue profiting at the expense of human lives. Samsung’s dominance isn’t merely economic; it reflects a neoliberal spirit that reduces workers to expendable assets within a sprawling machine that feigns care through technological innovation, asking the viewer if such “solutions” will truly help or will it endlessly generate more and darker horror.

In contrast, Rhea Storr’s A Protest, A Celebration, A Mixed Message offers a joyful interpretation of resistance through the Leeds West Indian Carnival. Storr’s film, capturing this exuberant display of community spirit, became a cornerstone of the Infringes programme. The act of protesting joyfully as self-assertion is central to the film, highlighting how reclaiming public space in protest allows individuals to assert their identities. The photographer’s camera further underscores the power dynamics between subject and photographer, with parade participants becoming objects of spectatorship for the hegemonic gaze. Through noise, movement, and colour, Storr demonstrates how protest can be a vibrant, joyful act of reclaiming space and resisting colonial histories that seek to totalise identities, thus rendering them dead.

Similarly, Martha Atienza’s Anito finds resonance in the Ati-Atihan Festival, where a chaotic, vibrant procession envelops participants in an eruption of collective identity. The film’s imagery and soundscape invite viewers to experience a cultural syncretism that feels shapeless, formless, aimless, and even meaningless in its structure, yet full of life and liberation in the essence of being. Atienza’s film challenges the rigid imposition of identity, suggesting instead that identity is fluid, shaped by community, ancestors, madness and joy. Anito complements Storr’s work though not just in bridging geographies. They offer a vision of identity as an ongoing, liberating process, not defined from above but forged in collective, celebratory defiance.

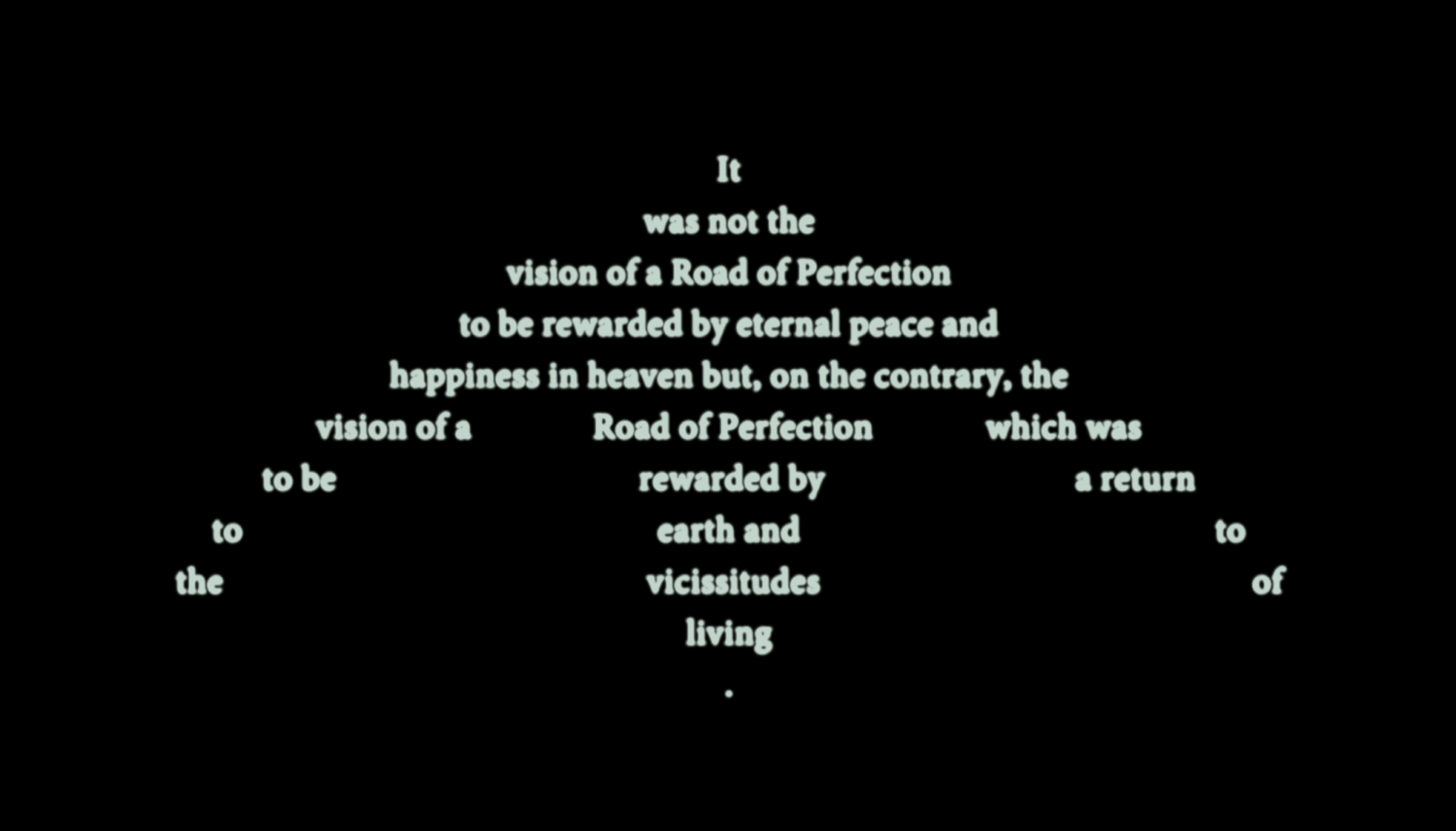

Closing the programme, Sky Hopinka’s I’ll Remember You As You Were, Not As What You’ll Become invites us into the realm of ancestral transcendence. Song and dance are not just cultural expressions—they transcend the boundaries of the spirit world, entering our plane to challenge the limited perceptions of reality imposed by dominant, logical modes of thinking. Through us, our ancestors protest. The neon Christian cross floating and dancing to Diane Burns’ performance, the Pow Wow dancers obscured in vibrant motion, and the appropriation of Paul Radin’s anthropological text into the shapes of ancestral effigy mounds act as a graceful cinematic resistance, reconnecting us with ways of knowing and being that exist outside the frameworks that have serve to suppress. In this space, the rhythms and visuals urge us to root ourselves in ancestral wisdom and embodied experiences, forging a path beyond the narrow confines of oppressive logics.

Looping back to Birth of Golden Snail, the programme becomes a circular confrontation with myth, narratives, and tradition. Infringes transforms the Thai Wattana Panich building’s dark halls into a space that reverberates with the stories and sounds we often ignore, and questions what we take for granted about identity, history, and power. Through film, sound, and myth, the programme disrupts and provokes, a call to reconsider the forces and bonds that shape our stories and, ultimately, our shared futures.

References:

Shira Schoenberg, “SJC taking up challenge to Harvard’s ownership of slave photos”, CommonWealth Beacon, 27 October 2021

“The DocYard presents: SHARED RESOURCES Q&A with Jordan Lord”, The DocYard, 1 May 2021

Top Koaysomboon, “Abandoned Brutalist buildings near Yaowarat’s Soi Nana resurrected as art space Bangkok Kunsthalle”, Time Out Bangkok, 15 January 2024

Kuakul Mornkum, “Rainbows that don’t wash away”, Bangkok Post, 27 May 2024

Punsita Ritthikarn, “Break free from world of sexual violence”, Bangkok Post, 14 Mar 2022

Matthew Hunt, “Birth of Golden Snail”, Dateline Bangkok, 20 December 2018

Stephanie Bailey, “Chulayarnnon Siriphol on Finding Ways to Express Opinions”, Ocula, 31 July 2020

Tendai John Mutambu, “Aura Satz Invites Us to Reimagine the Siren”, Ocula, 22 February 2024

“Jiří Žák Consensual Hallucinations and Poetic Investigation”, VALS Prague College, 19 May 2022

Theo Rollason, “A Cinematic Lingua Franca: An Interview with Riar Rizaldi”, Interview Online, 30 September 2024

Lucile Bourliaud ,“Interview with Rhea Storr”, Flat Pack Festival, 4 May 2020

www.kunstverein-wiesbaden.de/en/details/martha-atienza-/-fair-isles-1

www.moma.org/audio/playlist/298/4106

Osman Can Yerebakan, “Resisting Exploitation: Sky Hopinka by Osman Can Yerebakan”, Bomb Magazine, 24 September 2018

Komtouch Napattaloong is an artist, filmmaker, producer, and occasional film curator based in Bangkok. His works have been shown at CPH:DOX, BFI London, Visions du Réel, SGIFF, FFDJogja, Mar Del Plata, Bangkok Biennial, Protocinema’s A Few In Many Places, and Thailand Biennale’s Open World Cinema. In addition to his filmmaking, Komtouch has curated films for the SAC Anthropology Center film festival and a monthly screening series, as well as Objectif Center and In-Docs’ inaugural LENScape short documentary film programme. A Berlinale Talents 2024 participant, he was the programme producer for the Cinema For All pavilion curated by MoMa’s film curator Josh Siegel for the Thailand Biennale 2023.

Feature image: Still from Chulayarnnon Siriphol’s Birth of Golden Snail. Courtesy the Artist and Bangkok Kunsthalle