Interview: Through Self-Portraiture, Sang Woo Kim Is Reclaiming His Image

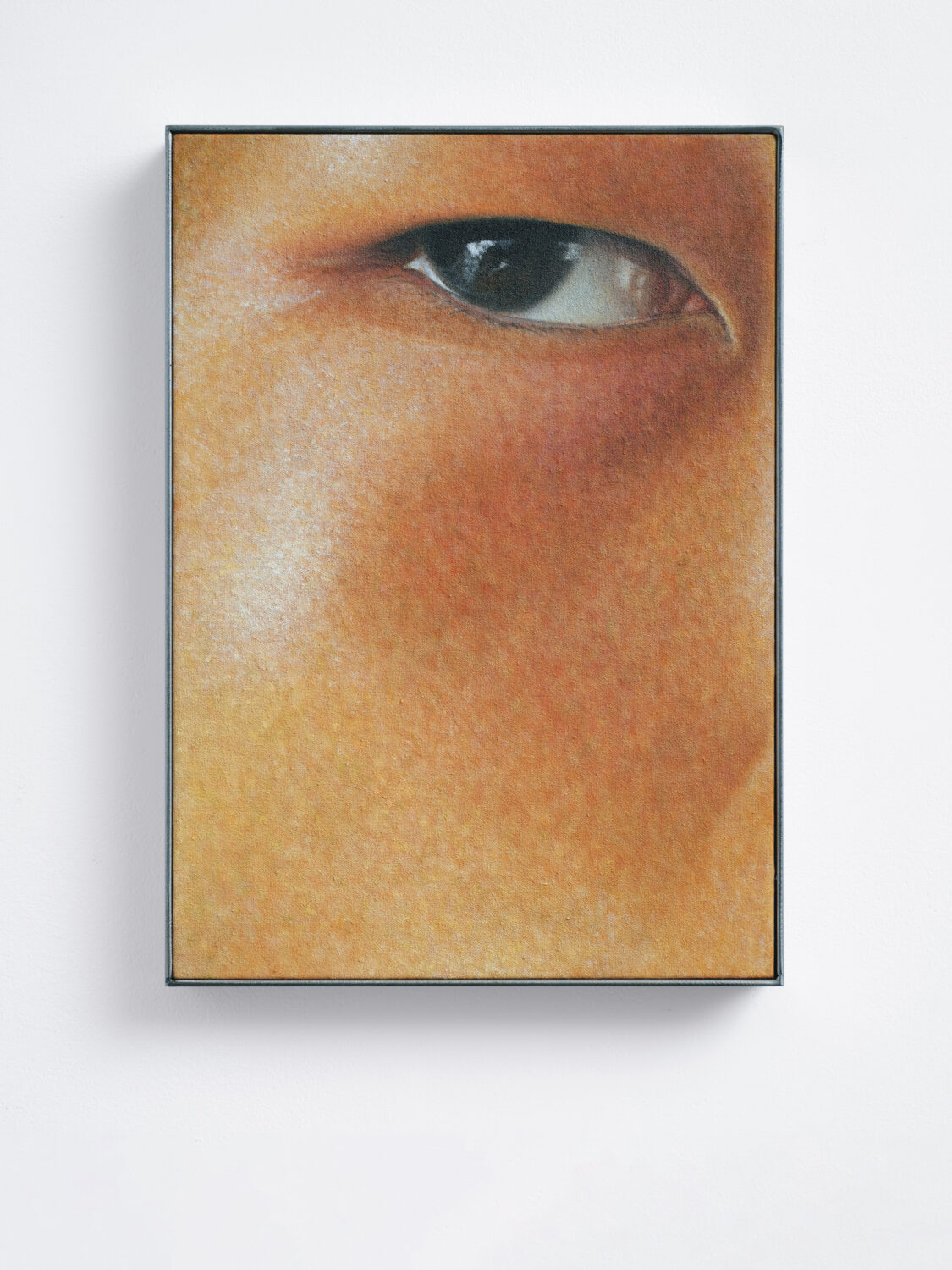

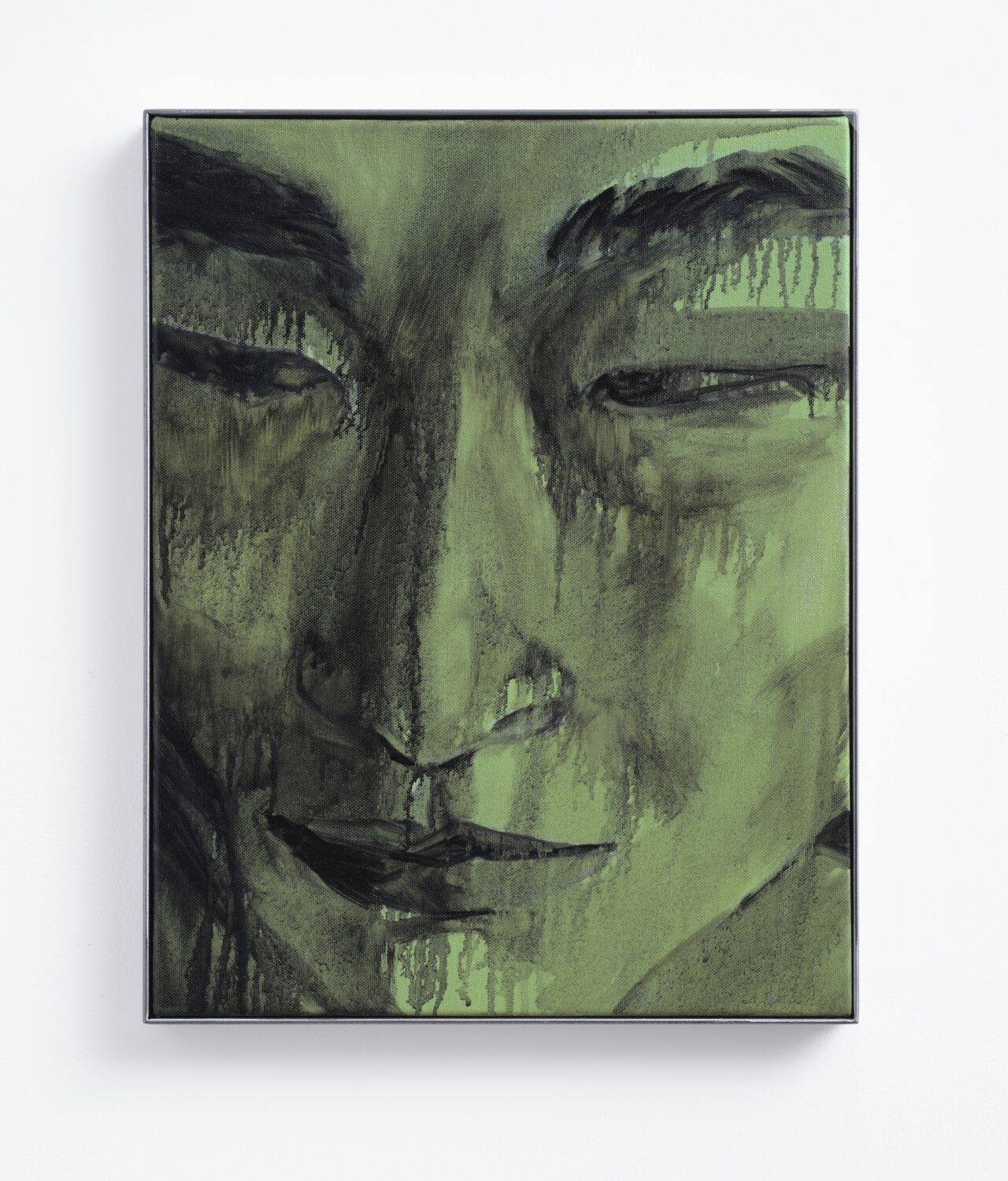

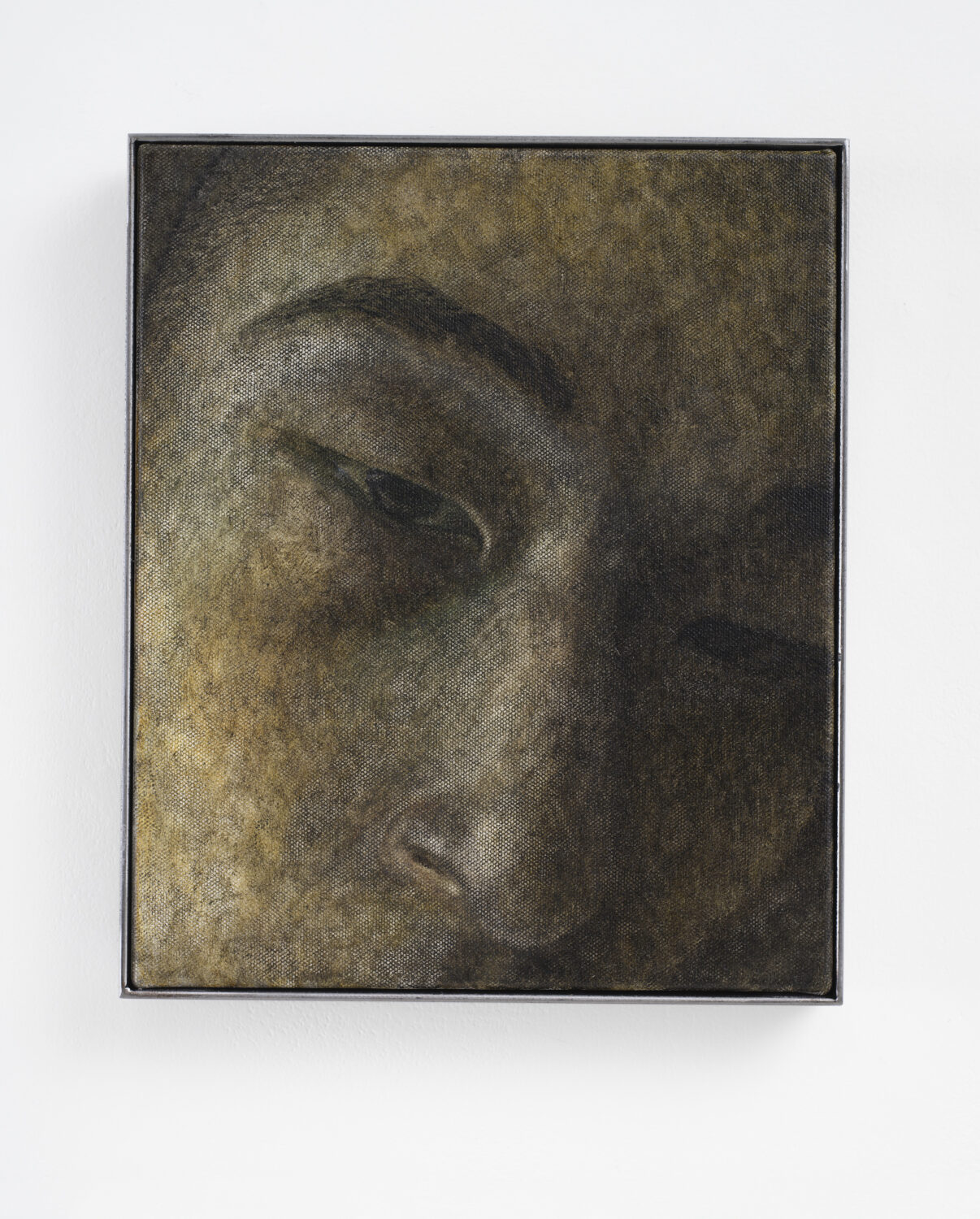

By Keshav AnandBorn in Seoul and raised in the UK from a young age, Sang Woo Kim probes the tensions and fragmentation of identity lived by many first-generation immigrants. Carefully navigating a space of cultural duality, Kim’s self-portraits explore his experiences as a Korean man coming of age in British society. Through close-cropped compositions and varied textures—ranging from smooth to gestural—the artist focuses on eyes as a central motif. By reinterpreting his gaze and contrasting it with others, Kim examines the tensions between racism, objectification, and self-definition, offering a layered dialogue on identity and power in his debut London solo exhibition at Herald St. To learn more, Something Curated’s Keshav Anand spoke with the artist.

Keshav Anand: The Seer, The Seen suggests a duality of observer and observed—could you elaborate on the thinking behind the show’s title?

Sang Woo Kim: The Seer, The Seen invites the viewers to consider who is the observer and who is the observed. The title of the show reflects the idea that the seer and the seen depend on each other to exist as they do, where perception, self-awareness, and reality are interconnected in an inseparable experience. The works in the show explore the nuanced relationship between image and physicality, self-perception and societal judgement, and our inner identity and how it is seen and understood by others. The works in the show meet the viewer’s gaze to challenge and provoke, inviting them to think about what it really means to see and be seen. We’re all one in our shared humanity, yet this show also seeks to convey that each of us still feels isolated within our own identity.

KA: How has your experience working as a model influenced your approach to self-portraiture?

SWK: First and foremost, my work is about the racial Otherness that’s been imposed on me by the Western gaze—a struggle that’s even more complicated by my experience as a model, where race is still the focal point due to the fetishisation that comes with that gaze. Through painting self-portraits, I’m trying to understand myself better and reclaim agency over my identity—finally taking control of a lost self that has been influenced by systemic racial bias.

I confront myself, painting with my own hands to reclaim my body, my image, and my identity from all the forces that have tried to define them—like looking into a mirror, not a glorified or editorialised image that has misrepresented me in the past. After years of feeling embarrassed by my image and identity, having no control over how I was perceived while growing up under the Western gaze, and being haunted by misrepresentative images that reduced me to mere physicality, I came to realise the importance of reclaiming my image and sense of self on my own terms.

KA: Identity in your work is both fragmented and concealed. What is the significance of not showing the entire face?

SWK: Not revealing my entirety is also a way to keep a part of me to myself. Painting self-portraits is vulnerable—it’s very exposing—but it’s also a way to face my insecurities and work through them. I guess I’m slowly revealing more through these works. They are glimpses, not the whole picture… at least not yet. As I delve deeper into understanding and becoming, I intend to reveal more of my face, body, and autonomy. I suppose we will see how the paintings evolve over time.

KA: What interests you in the eye as a recurring motif?

SWK: I focus on my eyes in my paintings, the gaze—which have been both the subject of discrimination and, later in life, admiration—I want to emphasise the juxtaposition that my eyes have come to represent in my life. It is also the reason why the crops are used to avoid showing the entire face, instead focusing on the gaze. Through the pigment dye transfer works, I explore the idea of perception—especially the stares and looks I’ve faced, often shaped by insecurities born from feeling othered.

This brings me to the concept of the gaze, both literal and metaphorical. These gazes, familiar yet foreign, create a tension between how I see myself and how I imagine others see me. At the same time, they gaze back at the viewer, inviting them to confront their own experiences with observation and vulnerability. I want viewers to reflect on how we perceive each other and ourselves in this increasingly visual world. These works don’t just highlight the act of seeing, but also the inherent vulnerability that comes with being seen.

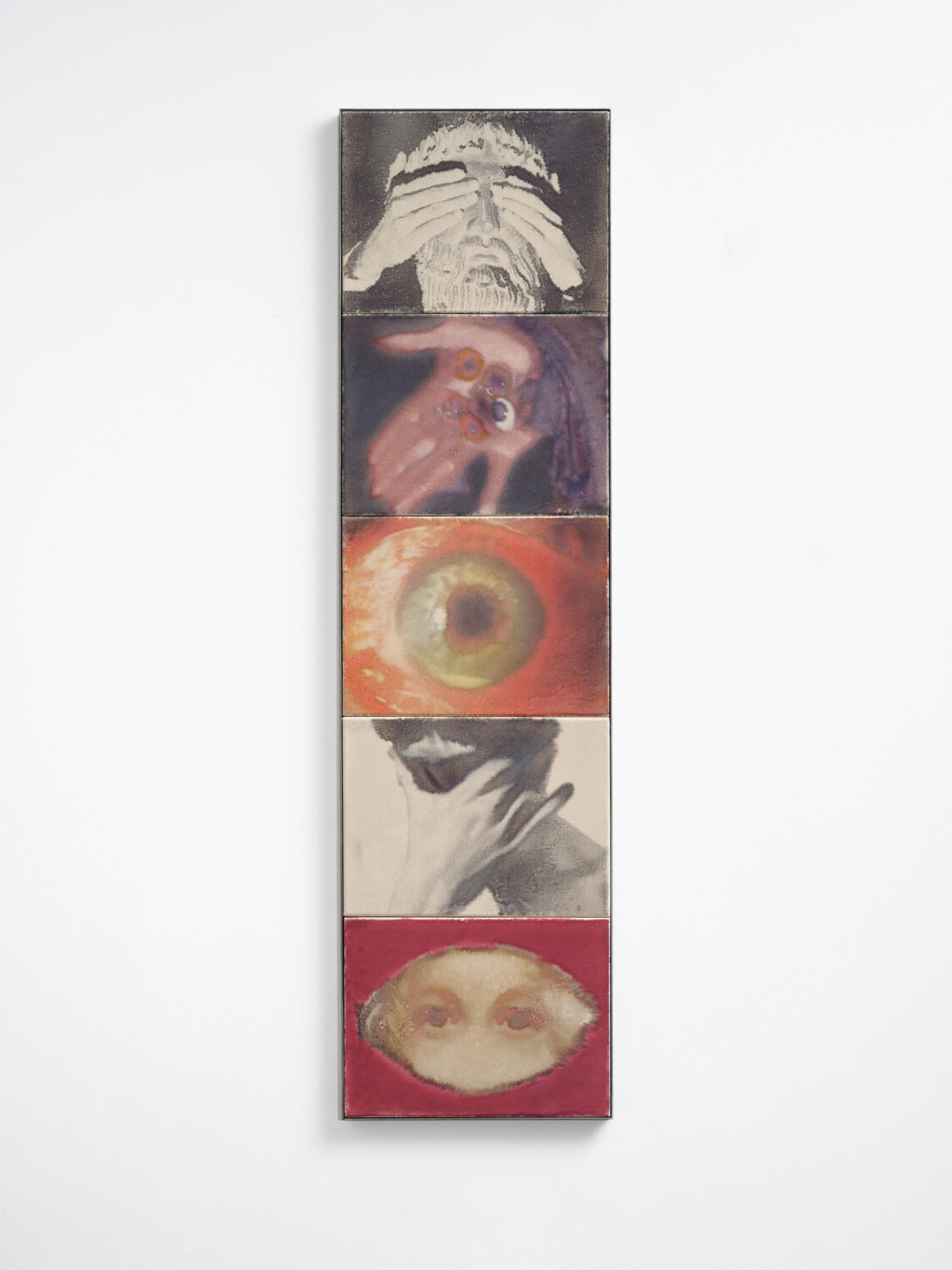

KA: You reference Robert Rauschenberg’s “painterly prints” as an influence on your pigment transfer works. I’m curious to learn what about Rauschenberg’s approach resonates with you.

SWK: This process, which I’ve been experimenting with for the past 10 years, was inspired by Robert Rauschenberg’s “painterly prints” from the early 1960s, where he incorporated found images from magazines and newspapers. People can now paint “photo-realistic” images—sometimes even more realistic than photographs—by manipulating depth of field to create “hyper-realistic” works that seem more real than a photo. The pigment dye transfer process and technique I developed stem from my fascination with image-making and the relationship between photography and painting.

It is also Rauschenberg’s unrestricted approach to new media techniques and printing that has influenced me to use modern technology and the tools accessible to my generation. I wanted to experiment with contemporary methods, seeing them as both a tool and a motif, driven by my obsession with painting. I often ask myself, “How can I create a photo that looks, or at least feels, like a painting?” This curiosity makes me question what defines a painting. Is it the process? If people can paint like photographs, I want to make photographs that act like paintings.

The process-based nature of pigment dye transfers also plays an essential role in the appropriation of existing imagery. This technique transforms each image, creating a shift from its original form to something that feels different, almost “Other.” Through this process, I manipulate the found image so that, although its composition remains the same, it is no longer perceived in its original form. Instead, it becomes imbued with new qualities—washed-out, melancholic, or even unsettling. These transfers add layers of nostalgia and decay, producing an effect that encourages viewers to look beyond the original image’s content and composition, experiencing it in an altered state.

KA: What are you currently reading?

SWK: Stages: On Dying, Working, and Feeling by Rachel Kauder Nalebuff and I Paint What I Want to See by Philip Guston.

KA: And do you have a favourite restaurant in London that you can share with us?

SWK: My favourite bar is 392 Kingsland Road, and for restaurants, I think Elliot’s is consistently great—both in quality and service, with lovely staff. However, my absolute favourite place to eat is at home, enjoying my mum’s homemade Korean food.

Sang Woo Kim’s The Seer, The Seen is on view at London’s Herald St gallery until 18 December 2024.

Feature image: Sang Woo Kim, You’re looking at me 005, 2024. © Sang Woo Kim. The Seer, The Seen, Herald St, London, 2024. Courtesy the artist and Herald St, London. Photo by Jackson White