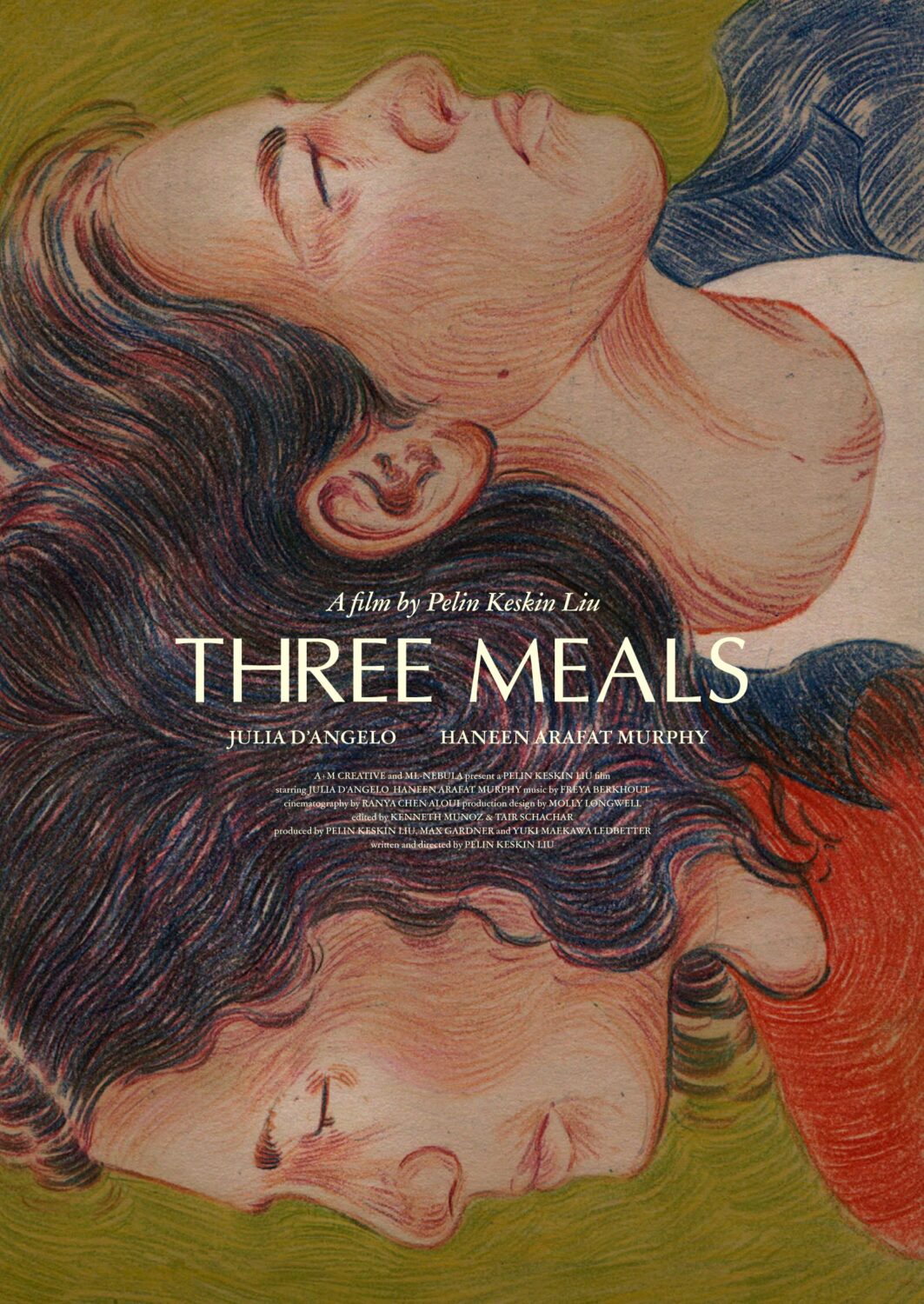

A Complicated Blend of Love, Misunderstanding, and Self-sacrifice: Director Pelin Keskin Liu on ‘Three Meals’

By Adam CoghlanWriter-director Pelin Keskin Liu’s debut short film Three Meals is a masterful portrait of the complexities, tensions and generational misunderstandings at the core of a relationship between a mother and daughter living very different lives. Yasmin and Suzy live apart – a metaphor for their having grown apart – but in the film they come together. Three meals – shorba, shakshouka, and stuffed vine leaves – separate the three acts; cooking and the preparation of food serves as a substitute for the pair’s mutual love and affection. Keskin Liu describes food as “the third character”: one that fills the void left by absent family, it preoccupies the pair as they appear unable to escape the dynamic they’ve unwittingly, tragically created. Shot on film in one location, the picture is texturally rich; it feels both old and new, trapping each of the characters in their learned roles as they grow older while trying to move forward at the same time as looking backward. Three Meals is a film about love, hope, and stasis – an extremely sensitive tribute to the complexities of human beings and the family units that contain them.

Three Meals is currently on the festival circuit and can’t be publicly released online until that concludes, which will likely be next August. Once that’s done, it’ll be available on Vimeo.

Update, February 2025. Three Meals will show as part of the ‘Reframe and Rejoice – International Women’s Day Shorts Showcase’ at the BFI in London on Saturday 8 March. You can find tickets, which includes a Q&A with the filmmaker, here.

For now, you can watch the official trailer below.

Adam Coghlan: What’s the genesis of this film?

Pelin Keskin Liu: I wanted to make a short film because I’d promised myself I would. Then I got laid off, which gave me a lot of free time to focus on this. Logistically, I needed to keep costs low, so I designed the story to take place in one location with just two actors. Thematically, I wanted the film to explore food and its symbolic meaning, focusing on the dynamic between a mother and daughter. This felt personal to me, as many of my significant arguments with my mother have happened in the kitchen, where power dynamics become particularly apparent.

AC: Why did you choose the mother-daughter relationship as the focal point of the story?

PKL: The relationship felt natural and compelling. There’s something deeply emotional about how arguments and power struggles often surface in the kitchen, where acts of care (like cooking) can clash with familial tensions. It’s a space where we’re our most stripped-back selves.

AC: Why a short film instead of a feature?

PKL: This was my first attempt at narrative filmmaking, and a short film felt manageable given my experience with one-day documentary shoots. A feature would’ve been overwhelming as a first step.

AC: How much of the film is based on your personal experiences?

PKL: The emotional core and the caregiving dynamic are drawn from my life. I have a sibling I’ve helped care for alongside my parents, and the line in the film about wishing a child would pass before their parent is something my mom has said. However, the characters and situations have been altered to serve the story.

AC: What are some of the inspirations and references for your style? It’s beautiful, very still, and I felt that there was a massive weight of absence.

PKL: Chantal Akerman was a major influence, particularly her films News from Home and Jeanne Dielman. Her ability to capture the quiet, repetitive, and deeply personal aspects of life resonated with me. I also aimed for a minimalist, observational tone that aligns with her style.

AC: Why did you choose food as a narrative device?

PKL: Food serves as a third character in the film. It symbolizes care and love but also avoidance — an act of giving that sometimes replaces the emotional vulnerability needed for honest communication.

AC: Do you think food is a form of love or something that exists in place of it? I found this to be a question I was asking myself as I was watching the film.

PKL: It’s one of those things that a lot of immigrant kids talk about, but at this point, it’s honestly really annoying. You know, the whole “cutting fruit” thing — the gesture where they can’t express their feelings, so they show love through food. I’ve always resented that. Sure, it’s true, but why does it have to be that way? Why can’t my parents just say “sorry”? Why do I need the bowl of fruit to know they care? I don’t find it sweet. I don’t get all misty-eyed over my parents being unable to apologize directly, so they give me a fruit bowl instead. To me, it’s not enough.

In the context of this film, I wanted that gesture to symbolize something deeper — an avoidance of honesty, of real emotional engagement. The mother, especially, avoids any kind of introspection. The lunch scene, for me, is the most obvious example of this. She becomes defensive, just focuses on making soup, and dodges any real questions or emotional conversations. It’s clear to me that she uses the food as a crutch — a way to avoid confronting the difficult issues at hand.

The food is lovely, and I appreciate it. I love that my mom cooks for me and does what she can. I totally recognize that, but it’s just not enough. It doesn’t replace the need for honest emotional exchange. I really wanted to show that in the film — all this food, all this love, and it seems sweet, but it doesn’t address the real issues. You’re left with someone trying to have a serious conversation, but the other person just keeps missing the point. Food, and love, are important, but they aren’t everything. Love isn’t enough if it doesn’t come with honesty.

AC: The moment when the mum tells the daughter that she wanted to be an investigator and she kind of lets down her guard for what feels like the only time, it causes Yasmin to kind of break down. I was interested by this (tragic) dynamic: where as each woman engages in a form of release, it has the effect of bringing back up the mother’s guard, and preventing the connection that they each want? Did you want to convey a kind of tragic, unresolvable distance here? And is it actually about protection and self-preservation?

PKL: When the mother finally lets her guard down, it’s because she feels bad for not understanding her daughter, but the tragedy is that she only sees her daughter revert to a childlike state. As a parent, you have to drop everything for your child, to protect them, even if it means setting aside your own needs. The mother puts her guard back up because she feels she has to be “mum” — the one who sacrifices. She doesn’t want her daughter to take on that role, but in doing so, she’s breaking the cycle of emotional sacrifice. She knows that even if her daughter stays, it won’t make her happy, just like it didn’t make her happy.

I wanted the film to end tragically — when the daughter asks about the flight, the mother knows it’ll all go back to normal once she leaves. The daughter wants to stay, but it’s a temporary fix. It’s bittersweet for both of them, because while they love each other, they can’t escape the reality that their lives won’t change unless they break out of that cycle.

This dynamic also shows up in families with siblings, especially when one has to care for an aging parent while the other doesn’t. The one doing the care often carries the emotional burden, even though both siblings are doing what they feel is necessary.

AC: What do you want viewers to take away from the film?

PKL: I hope people see their parents as individuals doing their best, even if their actions sometimes fall short. The parent-child relationship is a complicated blend of love, misunderstanding, and self-sacrifice, and I wanted to capture that complexity without simplifying it.

AC: Has your mom seen the film? What was her reaction?

PKL: Yes, she was one of the first to see it. She’s watched it multiple times and cried every time. She’s been incredibly supportive throughout the process and even collaborated with me during pre-production.

AC: What’s next for Pelin, the filmmaker?

PKL: I’m applying to film school in the UK, which could mark the next chapter in my filmmaking journey. Until then, I’m focused on refining my craft and telling more stories.

This interview was edited for clarity.

Photography courtesy of Three Meals film.