In the Studio with Steph Huang

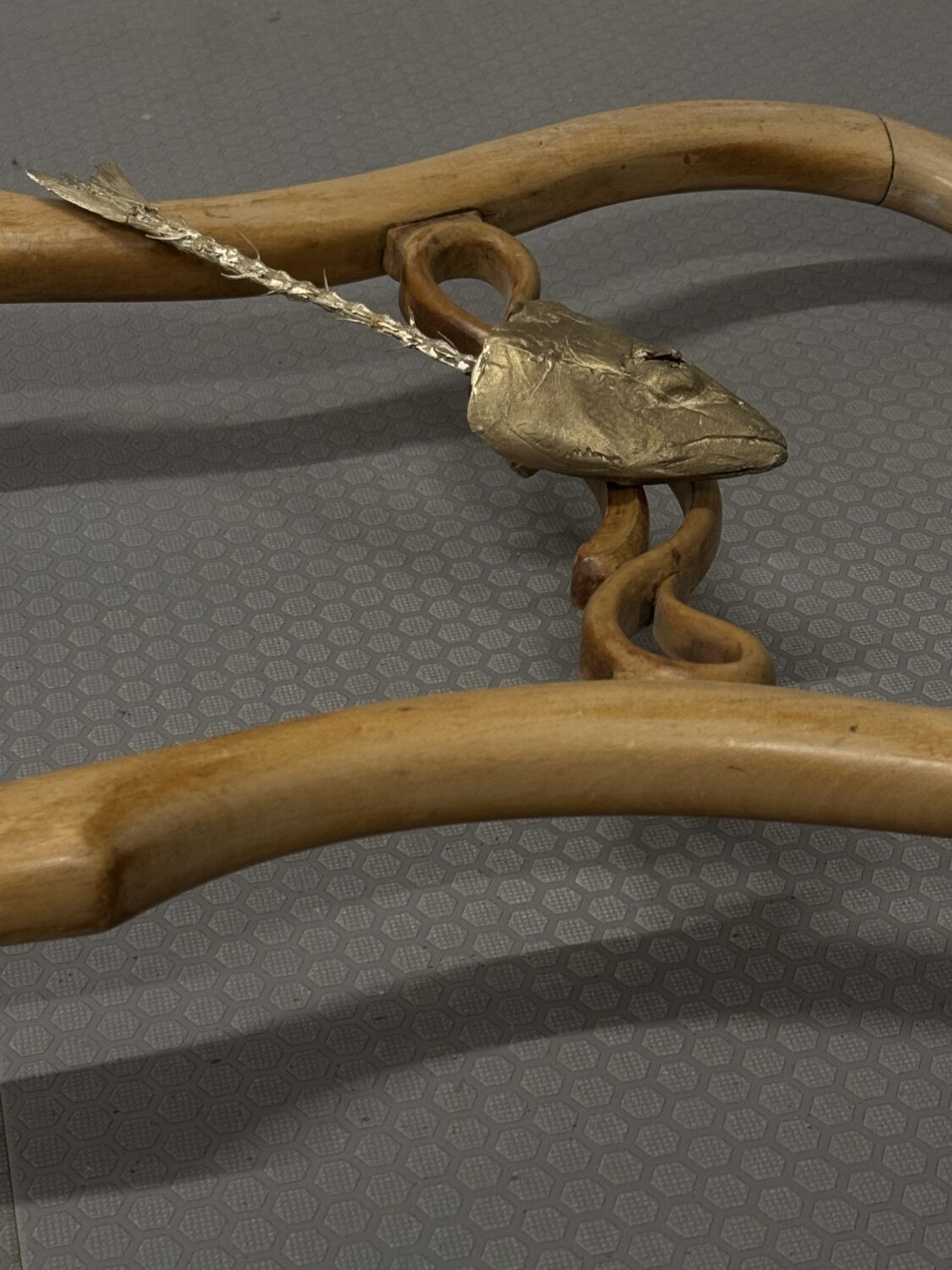

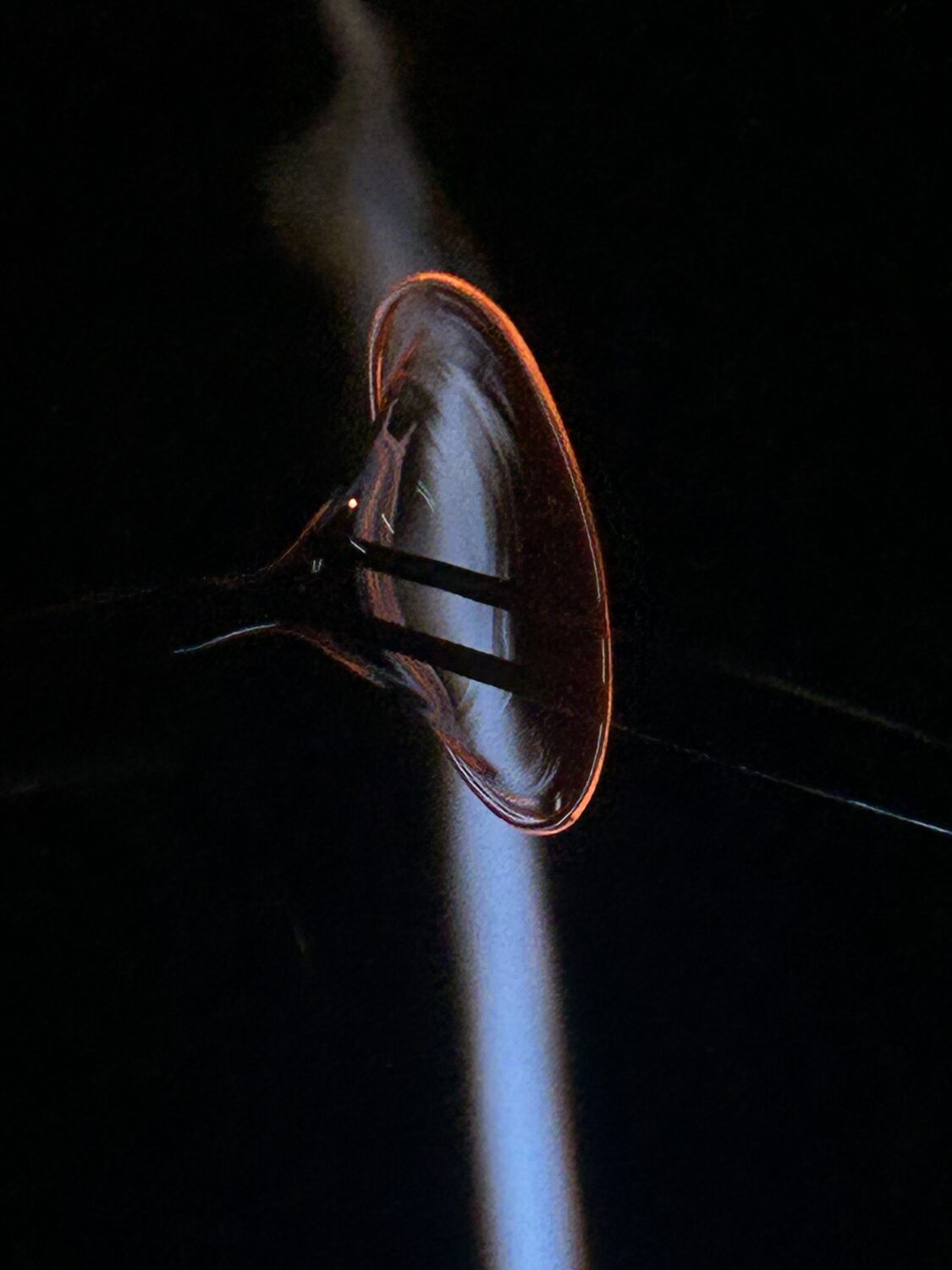

By Keshav AnandStep into the world of Steph Huang, the London-based Taiwanese artist whose poetic practice traverses diverse techniques and media, from glass blowing and bronze casting, to filmmaking and sound. Born in 1990 in Taiwan, Huang’s work draws on autobiographical narratives and traditions of storytelling, underscoring the eccentricities of everyday life. Currently the subject of Art Now: Steph Huang: See, See, Sea at Tate Britain, her latest exhibition reflects on the cultural and environmental impact of maritime trade, using found objects, sound, video, and sculpture to examine cycles of production and their influence on what, how, and where we eat. To learn more, Something Curated visited Huang’s studio.

Keshav Anand: What drew you to London?

Steph Huang: Taiwan is not a particularly big country, and I have always been drawn to the vastness of the world beyond it. London seemed like the place for me to explore my curiosity for art and life—it presented itself as a vibrant city full of diversity, openness, and opportunity. I’m very glad I came because I’ve had the privilege of meeting many remarkable individuals since then.

KA: Your work addresses the increasing disconnection between people and their food sources. When did you recognise this was an issue you wanted to explore, and what interests you about it?

SH: When I relocated here, I noticed that average Londoners rely heavily on chain supermarkets. They tend to grab an industrially made sandwich and packets of crisps for lunch, and vacuum-sealed cucumbers, plastic-wrapped vegetables, and microwavable ready meals are standard items in their shopping carts during weekly grocery trips. People can mindlessly complete their entire shopping experience without making eye contact or pausing the music flowing in their headphones. I’m sentimental about the growing alienation between people and their food, and with each other.

There’s also a growing market for delivery services that provide a custom recipe with each teaspoon of spices and sauces individually packed in plastic (assuming at least people might have salt and pepper handy at home)! I’m particularly intrigued by the psychology behind the industries that support our increasing alienation from each other and our food, and the materials I use in my practice allow me to express and explore these idiosyncrasies.

KA: While researching, what were some of the most surprising discoveries you made during your visits to seaside towns and fish markets across the UK?

SH: Despite the documentaries and conspiracy theories suggesting that sustainable seafood is a myth, I found out that fisherpeople genuinely prioritise the well-being of the fish and the sustainability of the ocean, knowing firsthand that it can feed generations of family and teach them many of life’s principles. Thanks to Sarah Ready, I’ve had the pleasure of meeting the local skippers, willow lobster pot makers and scallop divers in Brixham, all of whom share captivating narratives and great humanity. The problem is not with the individuals who work with and among our ecosystems but rather with the competitive industries that make sustainable lifestyles so unaffordable, priding efficiency and profit over nature and community.

I also learned that seafood is not a significant part of Britain’s dining tables. We all love battered cod and haddock from chippies, but these two species, along with salmon, tuna, and prawns, together account for eighty percent of seafood consumption in the UK. This rather narrowed interest has resulted in most of the fresh catch being exported to neighbouring countries.

KA: The materials you utilise often highlight contradictions. I’m curious to understand more about how you’ve approached selecting the materials—from glass and bronze to a supermarket trolley—that appear in the work in this show.

SH: I am deeply fascinated by materials, far more so than academic theories. I am captivated by their physical attributes, characteristics and the potential outcomes that arise from gaining proficiency in the requisite skills. I spend a considerable amount of time contemplating them in my studio before any tangible results manifest. As a contemporary sculptor, I have never carved out of stone; rather, I am interested in the process of combining the found with the made to create new installations in a designated space.

KA: How has the architecture of Tate Britain’s galleries informed your exhibition?

SH: Tate Britain is a prestigious building that houses some of the best collections spanning various eras. To work with curator Amy Emmerson Martin and present my work among many established artists still feels like a dream. For my Art Now exhibition, I had to work with the high ceilings, the pre-existing floating wall and some safety and accessibility constraints. With the tech team led by Mikei Hall, we installed the works at various heights to play with the viewers’ perception of space. I think my work is all about perspective, both conceptually and physically, in how it engages the audience.

KA: What are you currently reading?

SH: Ghost Town, a novel by Kevin Chen about a man who returns to his childhood home. The story is set against the backdrop of Taiwan’s history, rural customs, and superstitions.

Art Now: Steph Huang: See, See, Sea is on view at Tate Britain until 5 January 2025.

Feature image: Steph Huang, Prawn Cocktail, 2023. Courtesy the artist and Public Gallery, London