Bangkok’s Experimental Film Festival Returns After Twelve Years

By Kamori OsthanandaAfter a 12-year hiatus, the Bangkok Experimental Film Festival (BEFF) founded by Thai filmmaker Apichatpong Weerasethakul and curator Gridthiya Gaweewong, is back for its 7th edition. The Festival showcases over 120 experimental works across 29 programs. The singularity of this edition lies in its scale and two notion-defying works: A Conversation with the Sun, and An Encounter: The Last Thing You Saw That Felt Like a Movie.

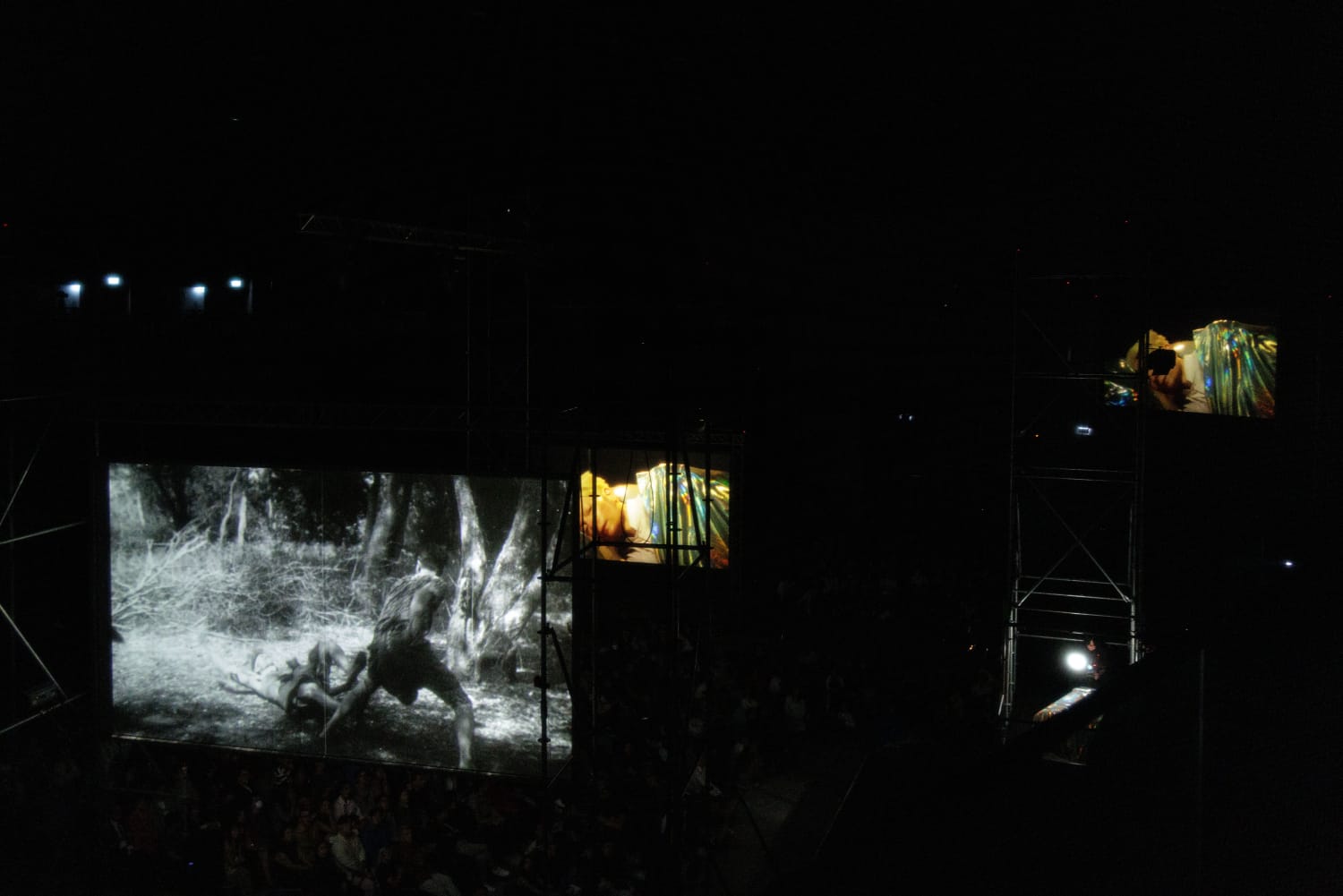

An Encounter: The Last Thing You Saw that Felt Like a Movie

In a half-asleep, half-dreaming state, Tilda Swinton lies silently in bed, blanketed in silver and iridescence. In a pink nightgown, she seemingly sleeps suspended in midair buoyed by the industrial steel structure eerily similar to ones in a film set. Surrounded by three screens in different directions, silent films—like dreams—seep in and out of the actress’ consciousness. Enabled by a myriad of archival footage appearing asynchronously on opposite screens, we witness selections from the Thai Film Archive and public domain. A diverse array of works from Thai films from the 1930s, D. W. Griffith, to Germaine Dulac, faded in and out of sight.

Swinton remarked in a following session that films have historically portrayed the cinematic women as transparent, and contingently without mystery nor function. Therefore, to showcase such montages involving Germaine Dulac and women-centricity allows for the inner lives of women to be explored. She mentioned former Hong Kong film director Tang Shu Shuen’s The Arch (1968), one of the first arthouse films produced in Hong Kong, which explores the nuanced psychology of a widow’s conflict with societal expectations and personal desires, as an example.

An Encounter probes the “dismantling” and “collapsing” of time that is the cinema, with moving images of the past that play before one in the present—in Swinton’s words. The performance also encourages the reframing of the gaze; to master the desensitization to multiple screens invariably without reverting back to Swinton, the performer, as a point of reference to cohere and cohesively contemplate. The space lends itself to the audience to take comfort in semantic loopholes that inkle a poetical narrative, similar to cinematic storytelling. The performance irrevocably reaffirms the vital consciousness of the audience whose presence and awareness transforms the innerdialogue Swinton has with hers amidst moving images that are peripheral ghosts; dead in spirit, living in name and resonance.

It also meditates the inner lives of film subjects by subverting the directorial gaze; and pushes the boundaries of experimental moving images that underpin the Festival. According to Swinton, inarticulacy and the acknowledgement of delicacy in communicating the inarticulate brings about fragility and wonder that is similar to poetry and pure cinema. It came as no surprise that An Encounter concluded with the live reading of individually selected poems in turns. Weerasethakul read In order to talk with the dead by Jorge Teillier and The Umbrella by Uten Mahamid, while Swinton read When Death Comes by Mary Oliver, Keeping Things Whole by Mark Strand, and Make Friends with Chaos by the actress herself.

Applause erupted as Strand’s words left Swinton’s lips, as if echoing the sentiment of the cinema and its audience: “I move to keep things whole.”

A Conversation with the Sun (VR)

To watch cinema in a space that is dialectically tangential to the cinematic experience is an act of self-confrontation. To malleate and expand the frame onto one’s surroundings, whether it be in perceived or virtual reality, heightened or lowered consciousness, is akin to holding up a mirror to oneself. A Conversation with the Sun abets in a trepidatious, sensorial soundscape, with brilliant sound design by the late composer Ryuichi Sakamoto and visuals by Katsuya Taniguchi. Each phantasmagorical scene becomes more anxious than the last, not because the scenes are any less dreamlike, but because it enticingly invites the subconscious to speak; it makes each and every Freudian slip permissible. The VR component of the experience underscores the human ability to sleepwalk in the waking world. The question is, though, are we getting any closer to the truth in waking consciousness?

Kamori Osthananda speaks with Apichatpong Weerasethakul and Gridthiya Gaweewong

Kamori Osthananda: Taking a retrospective look at the evolution of experimental film, how has it informed how you think about filmmaking?

Apichatpong Weerasethakul: Prior to the first edition of the Festival, I didn’t feel that experimental film was art. They were not in museums back then in the capacity that we see them today. There was Nam June Paik who was redefining video art as art, though there was not a direct label of “experimental film” as an art form. When I saw the works of Isaac Julien, there were still questions of whether or not such works belonged to the art world during the time. During the 1990s to 2000s, these works really came about everywhere and it made us question everything.

Gridthiya Gaweewong: It was around 1994 to 1996 when I arrived in Chicago and Garry Hill was everywhere. Everywhere I looked, I saw his video art. He [Apichatpong] went to see the works of video artist Douglas Gordon. And we were exposed to these works that reminded me of what shaped me. I grew up with cinema, my family and friends own cinema houses where I came from. I would watch a film anywhere, anytime—that was how I grew up.

AW: It reminded me of Khon Kaen where we would go into cinemas to watch a film halfway until it looped and that was typical. I think it was Hitchcock who was first to say that you cannot watch Psycho in a loop. That he wouldn’t allow his film to be watched that way.

KO: An Encounter is a notion-defying singular lecture-performance that pushes the boundaries of cinema. What was the process of conceptualizing it? How does watching it come to life feel?

GG: I grew up with Thai outdoor cinema. With Apichatpong’s work in Baan Mae Ma in the Thailand Biennale in Chiang Rai 2023, and in An Encounter—it was a full circle moment. It was a dream come true. When I watched Tilda and Apichatpong doing what they do, amidst the film set with a backstage-feel, while thinking about a gesture of invitation for the audience to peek at something they haven’t seen before it was on screen, that was very special. To see an artist and a performer collaborate and work together, it felt as if witnessing a historical moment where we are literally opening up the possibilities of what cinema can be. I went home and I couldn’t sleep for hours. We shifted the gaze. We shared space with the film before it became one and once it became one. We expanded the frame.

AW: Back in the day, there was always a cinematic form. Even experimental film at the time had a form. An Encounter expanded the notion of what cinema is because you are the editor. You are the gaze. You pick and choose your screens and frames.

GG: We brought the behind-the-scenes to the audience. And having watched Tilda’s literary performance, being part of the audience, I felt that I was watching two worlds collide—Tilda’s and Apichatpong’s. You still have a very Apichatpong touch in the soundscape that constantly reminds you to tap into consciousness like in A Conversation with the Sun, but you are also exposed to so much more. So it doesn’t just expand cinema, it expands what film production is. That was very precious to me.

KO: What is the cinema now? How was it different when the Bangkok Experimental Film Festival first started?

AW: You don’t see such fixed ratios that determine what is cinema anymore. We start seeing discourse of whether a change in the cinematic context or content becomes what is definitive of the experimental quality, like in A Conversation with the Sun and An Encounter.

GG: Young people now are into films that are not mainstream more than in the past. I had never thought there would be such a large crowd for cinema until the present day. We used to see ten to twenty people in the room who all became filmmakers like Jit Phokaew. Now I see crowds of hundreds, will we have hundreds more filmmakers in the future? That’s exciting, no? The Festival is multidisciplinary, everything is interconnected. The worlds of moving images and fashion, for example, are no longer standalones.

KO: Last year, you both and Tilda Swinton were in Chiang Rai for the Thailand Biennale 2023 where the actress famously said in a talk “Cinema is ours.” What does that mean to you now?

AW: I think the question here is: cinema is ours, what are we going to do with it? Streaming platforms are dominating the space, everything is data and algorithms. In a production house, there are quality assurances of how a film is produced and how the storyline should evolve by the minute. That made me question, in this context: what is cinema? We now see beautiful cinematography but I still find myself drawn to films like Martin Arnold’s that punches you in the face when you watch them and asks you, “Do you think this is cinema?” It made me reflect on the mid-2000s. The projector became affordable, Thai independent cinema was growing. Now, the social infrastructure for filmmakers is much more in place. Streaming companies have a more structured approach to film production which means more profitability. But where creativity remains in all this, I’m not too sure.

GG: I think it’s now very much about democratization, as with An Encounter. You watch something while it is being produced, you are being let in backstage so to speak, and you have the right to redefine what you’re seeing.

AW: We have more filmmakers now but there’s not enough substance that challenges you. The magic of the collective environment in experiencing cinema prior to streaming services also felt like a dream. I wish that the younger generation would get to experience more of that. Collectiveness is important. We may think: when you have anything at the tips of your fingers readily available on your device, why would you watch a film anywhere beyond the premises of your home? But we can only dream together through collectiveness.

GG: I think there must be accessible spaces beyond streaming services for young people to engage with cinema and the cinematic experience.

KO: Are there any Festival highlights that you’d like to share?

AW: It’s funny because we founded the Festival because I wanted to watch films. But now it feels as if I don’t have the time to watch anything because I have so many things to tend to beyond the role of a filmmaker at the Festival [laughs].

GG: I’d say guest curators for this edition did a job well-done. Their programs are intriguing. Personally, my highlights would be Johan Grimonprez’s Dial H-I-S-T-O-R-Y (1997) and Yang ZhenZhong’s (I Know) I Will Die (2007).

The Bangkok Experimental Film Festival (BEFF) is taking place from 25 January to 2 February at One Bangkok Forum. The Bangkok Avant-Première of A Conversation with the Sun and the lecture-performance An Encounter: The Last Thing You Saw That Felt Like a Movie are supported by CHANEL.

Feature image: Courtesy of CHANEL