The Sri Lankan Photographer Who Hid Queerness in Plain Sight

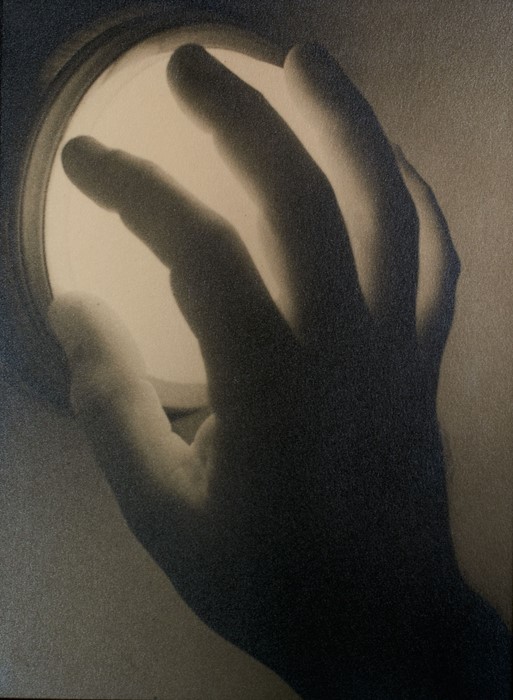

By Keshav AnandA man’s hand reaches towards an electric light source, his fingers tentatively caressing the glow, obscuring and revealing it at once. The image described is Lionel Wendt’s Bachelor Cruising South, shot in the mid-1930s. The photograph is quietly suggestive, its title a little less subtle, alluding to the pursuit of casual sexual encounters. It is a work that speaks in the language of desire, of shadows and light, of exposure and concealment, of queerness. Such images place Wendt firmly in the avant-garde of the early 20th century.

Born in Colombo in 1900, Wendt was part of the Burgher community of Sri Lanka, a mixed-race minority with European lineage. His upbringing was privileged. Initially trained in law at London’s Inner Temple, he simultaneously pursued music at the Royal Academy, where he developed a passion for experimental composition. His early career saw him as a concert pianist, performing Bach, Bartók, and jazz, but by the 1930s, photography had overtaken his musical aspirations.

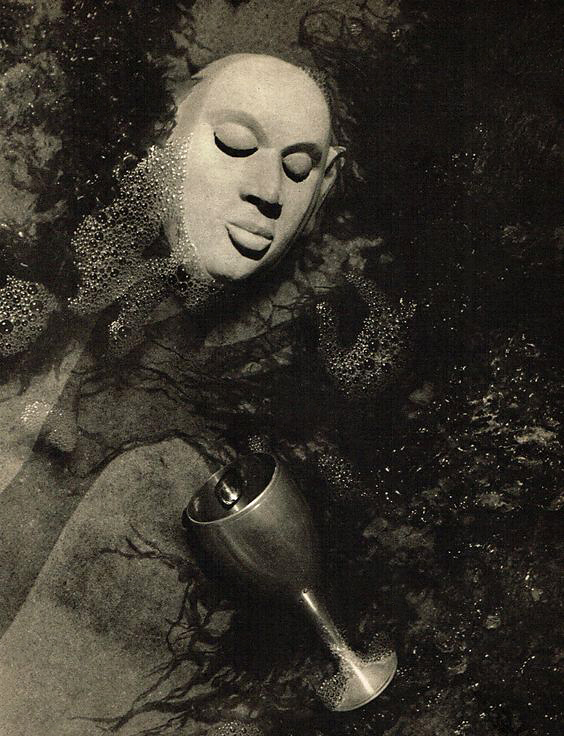

Wendt’s transition from sound to image was abrupt but absolute—he became consumed by the possibilities of the camera, experimenting tirelessly with photomontage, double printing, and solarisation, the latter inspired by Man Ray’s techniques.

Wendt’s work defied the aesthetic conventions of colonial Ceylon, challenging the romanticised, pictorialist images of tropical paradise favoured by British photographers. “His practice corresponds to a time in which the idea of what it meant to be from, and of, the nation of Ceylon was called into question as the island moved closer to independence from British rule,” writes Kaitlin Emmanuel. Wendt crafted a modernist visual language that was at once technically sophisticated and deeply personal.

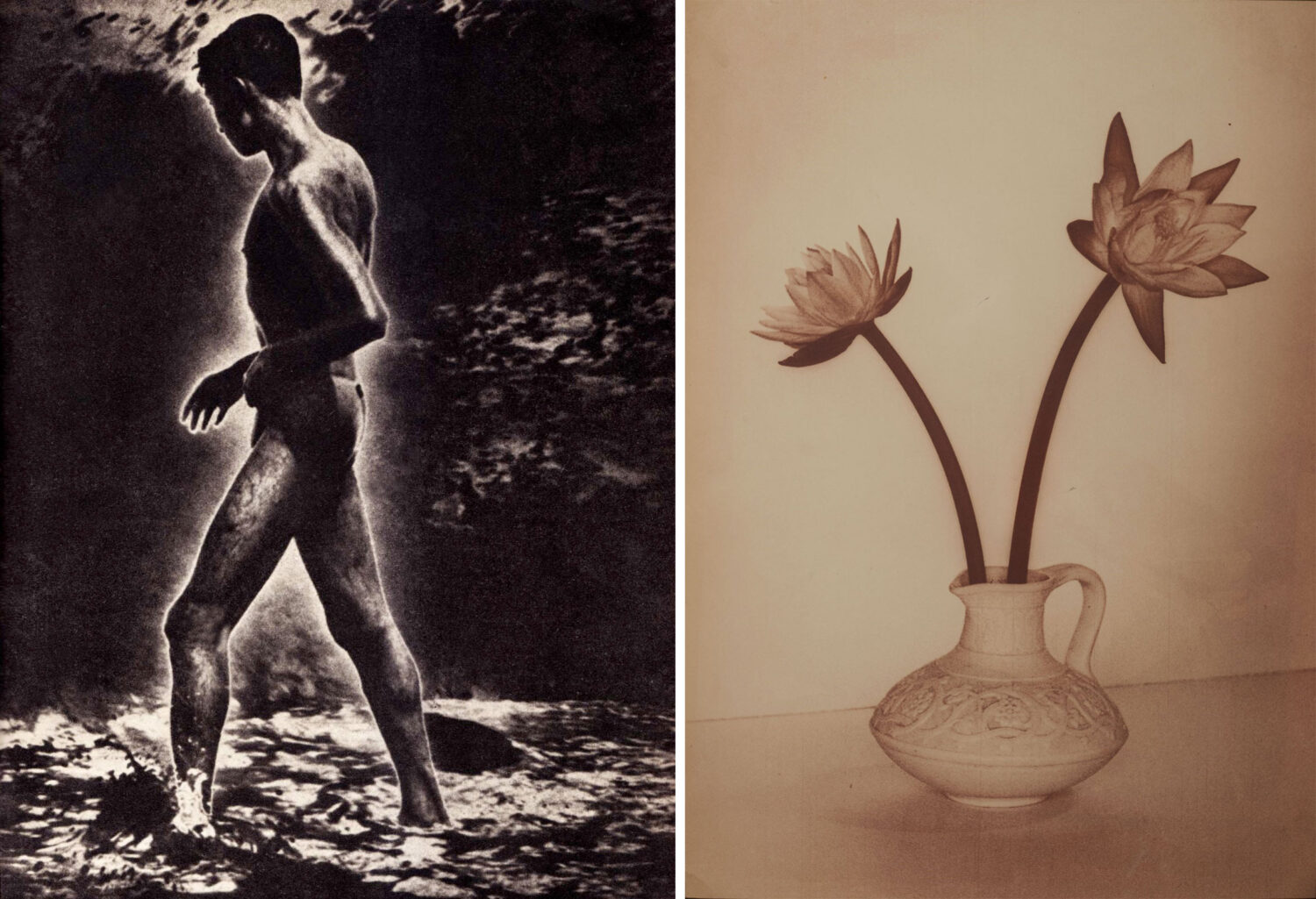

His portraits, particularly of the male nude, remain among the most radical ever produced in South Asia. “Wendt never publicly identified as homosexual, a historical identity category created in the nineteenth-century Global North, and spread through imperial rule… Wendt’s close friend, Burgher Sri Lankan painter George Keyt, remarked on his homosexuality in interviews, which was probably an open secret,” historian Dr Edwin Coomasaru points out.

Shot both outdoors and in his studio, Wendt’s photographs borrow inspiration from classical art, while forging new expressions of eroticism. His images fuse an interest in European aesthetics with a reverence for Indigenous Sri Lankan traditions—and bodies. In a country where homosexuality was unspoken and criminalised, which is technically still the case, his work was an act of defiant self-expression.

His artistic reputation extended beyond Sri Lanka’s shores. In 1938, Leica, the German camera manufacturer, sponsored his solo exhibition in London—a rare accolade. His involvement in Basil Wright’s documentary Song of Ceylon further cemented his international stature, with Wright crediting Wendt’s “profound knowledge of Ceylonese culture” for the film’s evocative imagery.

Alongside taking photographs, Wendt was a fierce advocate for the arts. His home, Alborada, became a gathering place for intellectuals, musicians, and visual artists who sought to break from the mould. In 1943, he co-founded the ‘43 Group, Sri Lanka’s first modernist art collective, bringing together painters such as George Keyt, Ivan Peries, and Justin Deraniyagala. The group endeavoured to create a distinctly Sri Lankan modernism, one that embraced both Indigenous traditions and contemporary global currents.

Just a year later, Wendt’s life was cut short when the photographer tragically died from a heart attack at the age of 44. In the wake of his death, his photographic negatives were largely destroyed, an incalculable loss to the history of modern photography. Yet his influence endured. A number of his images were later compiled in Lionel Wendt’s Ceylon (1950), a photobook that remains the most significant collection of his surviving work.

His legacy also lives on in the Lionel Wendt Centre for the Arts, established in Colombo in the 1950s on the site of his former residence. Housing a theatre and galleries, the cultural centre continues to operate as a nucleus for the city’s creative community, hosting an evolving programme of exhibitions, performances and events.

Feature image: Lionel Wendt, Untitled. © Lionel Wendt. Courtesy Jhaveri Contemporary, Mumbai