Ellipse and Ellipsis: A Manifesto for Spatial Listening

By Vittoria de FranchisEllipse and Ellipsis unfolds as a spatial manifesto, continuing a series of curatorial interventions I’ve developed in domestic or transient spaces over the past years. Focused on ephemeral media—voice, sound, performance, and site-specific installations—these practices shape the viewer–work–environment relationship through cohabitation. As the first curated exhibition at the Nicoletta Fiorucci Foundation, it felt essential to begin by making space: to transform Nicoletta Fiorucci’s carte blanche into an invitation for others to imagine.

From our earliest conversations, Nicoletta and I shared a conviction: the urgency of creating space for distension, for imagining beyond the suggested—and often imposed—dystopia, alongside a shared will to experiment with exhibition formats. The current geopolitical developments sparked a reflection on the historical loops we move through, patterns that repeat not only events, but also exclusions. With a curatorial practice rooted in language, I turned to words as a framework and possibility. Ellipse and ellipsis surfaced early on—both from the Greek elleipsis, meaning “falling short.” Though rooted in lack, they carry potential: one traces a returning cycle defined by the presence of otherness; the second marks a pause that invites continuation.Together, they suggest that repetition can be a catalyst for change, and that silence can create the conditions for unheard voices to emerge.

These terms didn’t remain metaphors but became the tonal anchors of a story, that of Ellipse and Ellipsis as two fantastical cities, staged through sound, installation, and design–shaping an environment in which ‘invisible architectures’ (or ‘peripheries’, as emerged in conversation with Daiga Grantina) come forward, activated. By this, I mean the elements that quietly shape experience: not only walls and furniture, but also narrative systems, sonic patterns and scores of movement. The exhibition became a device of decentralisation and entropy, where structure—both tangible and conceptual—functions like a score: something to be interpreted, written upon, and listened to.

The choice of artists to participate in Ellipse and Ellipsis was guided by a focus on practices that foster or expand space through different media. The first work—or prop, or note—to manifest was Scrambled Sky by Anthea Hamilton, part of the Nicoletta Fiorucci Collection: a cloudy environment of optical tension that offers a porous, digital-poetic landscape. Installed across all the walls of the exhibition, the wallpaper disrupts its own context, transforming edges into a pattern of fragmented sky. It renders architecture suggestive rather than directive—a spatial otherness in which to question, linger, or, as Anthea describes, “enter the shadowy sensation of culture.”[1]

From the outset, the intention was to include sound and shape as a space for embodied listening within the city—something masterfully realised by La Monte Young and Marian Zazeela in New York with the Dream House. Before considering what compositions would inhabit the space, I thought about their source and presence. This led to Elvio Seta, builder of his own Acousmonium—a hi-fi diffusion system inspired by François Bayle’s 1974 GRM model: each speaker calibrated for specific frequencies. I had worked with such systems in Italy, but rarely encountered them in exhibition contexts abroad. Eighteen of the thirty elements composing the Acousmonium ODAE travelled from Milan to London, forming a sculptural soundscape somewhere between minimalist installation and iridescent orchestra of speakers.

The idea was to mark time through sound and thus the exhibition, unfolding over the course of a spring, is punctuated by monthly sonic transitions. I invited artists for whom sound is integral—not as soundtrack, but as sculptural form. Jasper Marsalis, Sandra Mujinga, and Jota Mombaça were each commissioned to create a 33-minute loop—a quietly romantic duration where the two threes fold into infinity.

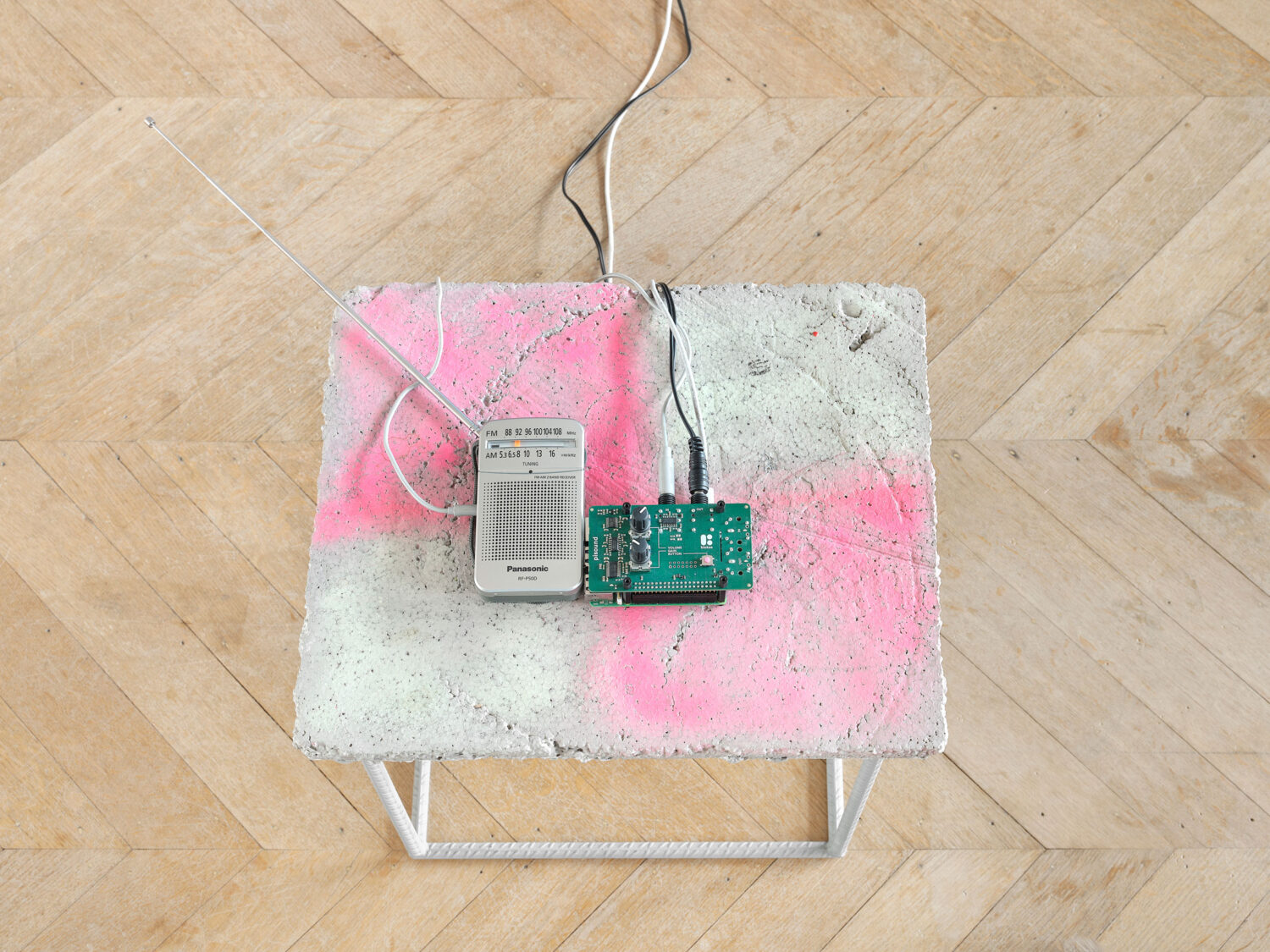

I had known Jasper Marsalis for some time through his musical project, Slauson Malone 1. When I visited his studio in London to discuss Ellipse and Ellipsis, he proposed Radio Meditation—an ongoing sound installation inspired by a listening exercise by Pauline Oliveros and Luigi Russolo’s early noise instruments. The piece, a generative exchange between a microcomputer and a radio tuned to BBC Radio 3, produces a shifting soundscape of orchestrated chance. Jasper’s practice doesn’t simply introduce sound into exhibition spaces; it foregrounds its infrastructure. Cables, speakers, and sources become visible, sculptural elements—installed here on a Stool by Eva Rothschild, from the Nicoletta Fiorucci Collection, placing the temporary architecture of sound in dialogue with the permanent elements of the space.

The second sound piece, Memory Stream by Sandra Mujinga, emerges from the artist’s engagement with the political potential of sound, offering a contemporary take on Afrofuturism. It weaves together the sound of a stream—recorded near her studio—with the memory of Patrice Lumumba’s historic 1960 Independence Day speech for Congo, which is made available for visitors to read in the exhibition. Mujinga composed three distinct versions of the same 11-minute loop, each subtly different, evoking speculative timelines in which water becomes both witness and agent of change. The piece carries forward the hope of Lumumba’s words and their resonance today—as technoculture remains deeply entangled with the ongoing exploitation of African futures.

Interestingly—though perhaps never coincidentally—following Jasper’s radio air(waves) and Sandra’s water, Jota Mombaça gives voice to fire. Their sound work, has the fire read the stories it burnt, invites a reconsideration of fire not as a force of erasure, but as a form of elemental listening—expanding listening beyond the human. Mombaça treats heat, and crackling as a re-decomposition of matter and language—a combustion that transforms rather than annihilates. The invitation came at a timely moment, as they had recently decided to deepen their focus on sonic practice beyond installation. This piece also marks the first in the exhibition to introduce voice as sonic material, layering a re-de-composed poem by Denise Ferreira da Silva with fragments of Mombaça’s short story Can You Sound Like Two Thousand? (2020).

The intention of including more-than-human voices and listeners within the space led me to revisit a series of speculative essays I had read on the effects of sound on plant life. I reached out to Gabriella Hirst, with whom I had been in conversation since the CIRCA PRIZE 2023—where she was a finalist and I was part of the Curators’ Circle—to explore the possibility of presenting Body Garden, a living installation from her ongoing research into gardens as spaces of critique and care, with a focus on the politics embedded in plant taxonomy. Twenty-five plants, each named after a body part, treatment, or vice, have been sourced and foraged to be installed in organ- and vessel-shaped pots—some second-hand, bearing the patina of time, others borrowed from Troy Town’s Hoxton Gardenware. Body Garden changes daily as the plants grow, decay, and adapt, marking time within the exhibition—a space intended to be returned to, where presence unfolds gradually.

Like the wallpaper and the Acousmonium, the garden held a possibility: of being more than it appeared, of creating a narrative space that extended beyond its physical presence. Within this exploration of domestic and spatial utopias, I invited the Greek design duo Objects of Common Interest, whose ongoing research on inflatables—first encountered during a Design Week in Milan—had long fascinated me for its ability to breathe new life into 20th-century pneumatic visions and radical spatial experiments. For Ellipse and Ellipsis, we commissioned six of their Inflatable Chair, which contributed to the exhibition’s suspended landscape and invited visitors to actively shape the space through movement, rest, and desire. Their inclusion also marked the duo’s introduction to the Nicoletta Fiorucci Collection, known for its strong focus on design.

Ultimately, Ellipse and Ellipsis does not offer solutions or spectacle. It is a proposal for how we might be with an artwork—not as consumers or observers, but as cohabitants. In a moment when the world constantly demands responses—action, position, acceleration—Ellipse and Ellipsis offers space. Not as escape, but as reclamation: a space in which to imagine beyond the dystopia we are given and eventually rest suspended in the air, being with music and looking at a cloudy sky or garden.

[1] Anthea Hamilton in Questionnaire: Anthea Hamilton, Frieze, Issue 195, 2018.

Ellipse and Ellipsis is on view until 21 June 2025 at The Nicoletta Fiorucci Foundation, London.

Feature image: Ellipse and Ellipsis at the Nicoletta Fiorucci Foundation, 2025. Photo: Eva Herzog