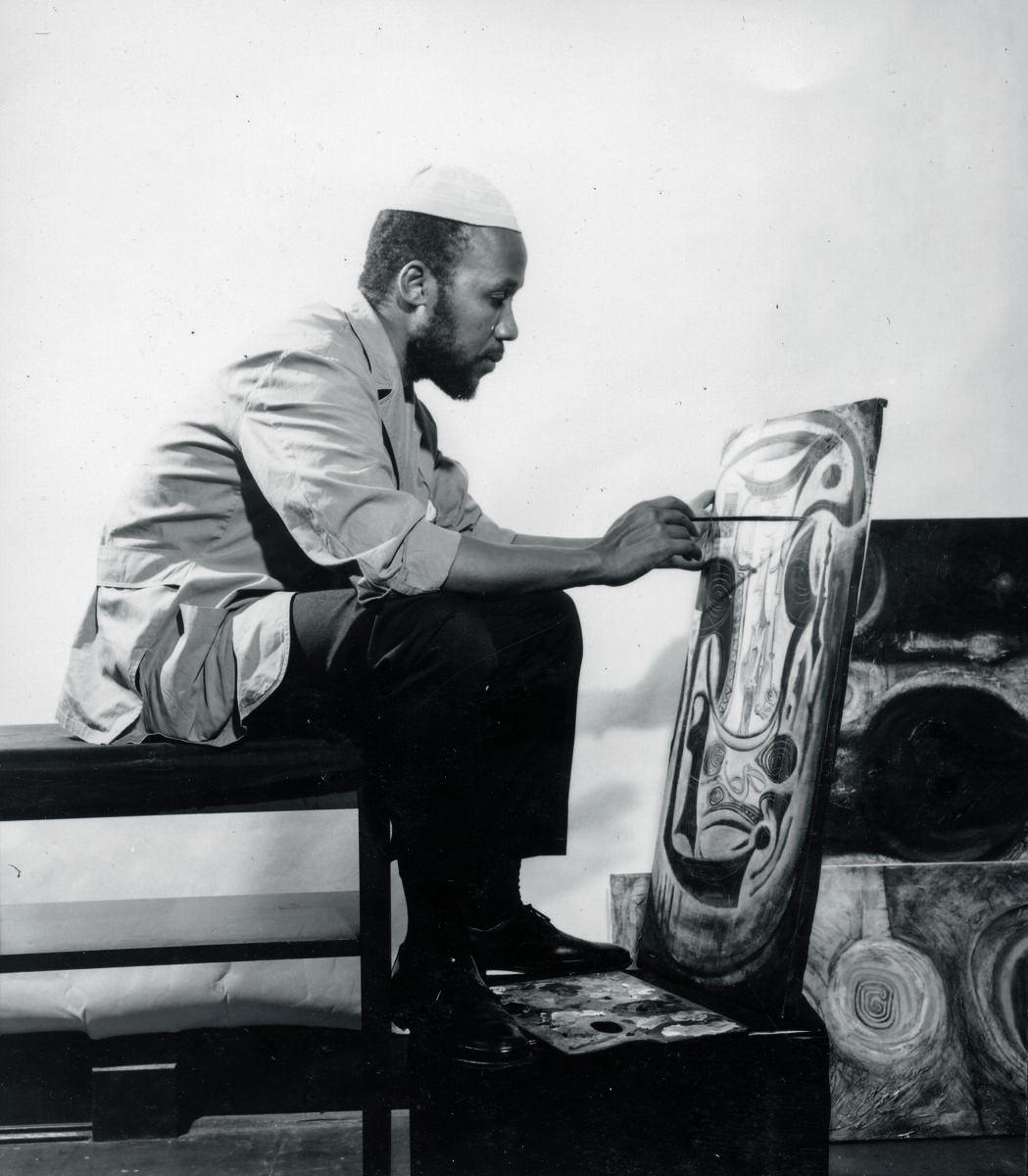

Ibrahim El-Salahi: Sudan’s Master of Modernism

By Keshav Anand“A picture is no more than a mirror, a vehicle that takes one back to one’s self, to turn one’s sight inwards to find the self within,” writes artist Ibrahim El-Salahi. Detailed and contemplative, his layered paintings feel at times like workings-out, arithmetic in brushstrokes. Born in 1930 in Omdurman, Sudan, El-Salahi is a pioneer of African Modernism and a founding member of the influential Khartoum School – a group of artists who collectively sought to forge a new visual language for an independent Sudan in the early 1960s.

Attending his father’s Qur’anic school as a child, El-Salahi’s work is greatly influenced by his early exposure to Arabic calligraphy. “That was my first school,” he says, in conversation with Abu Dhabi Project Curator, Sarah Dwider. “There, I was writing and decorating the writing and enjoying the space between the lines.” Displaying a keen interest in art from a young age, El-Salahi went onto study at the Gordon Memorial College in Khartoum: “It gave me the basic discipline needed for an art student. It also made me aware of the fact that I am a picture maker.”

Shortly after, an opportunity arose that took him to London. Earning a scholarship to study at the Slade School of Fine Art, it was in the UK that El-Salahi’s fascination with Modernism emerged. The young artist was immersed in a scene of creatives and academics who challenged and expanded his perspective. He recalls London in the 1950s as “like stepping into a new world. I loved the rain and the fog… the dimness and silence that enclosed everything in autumn – the total difference to what I knew at home.”

But even with all these new influences swirling around, he remained steadfastly interested in learning more about Islamic art. Exploring the British Museum and Victoria and Albert Museum’s vast historical collections, he began to draw parallels between European abstraction and the aesthetic traditions of the Arab world. These encounters became a catalyst, birthing a singular artistic language that fuses geographies and temporalities.

Upon returning to Sudan in 1957, after his studies, El-Salahi felt somewhat misunderstood. As Perrin Lathrop, Assistant Curator of African Art at Princeton University Art Museum, elaborates: “Back in Sudan, El-Salahi began to teach painting at the School of Fine and Applied Arts in Khartoum, where he was a founding member of the Khartoum School. His disappointment in the reception among Sudanese audiences of the work he had produced at the Slade School motivated the shift in his practice.”

El-Salahi himself remembers this moment vividly: “I was deeply disappointed. But it taught me a valuable lesson. To address others there has to be something in common. There has to be a bridge of mutual respect and understanding of what the other has and practices.” Looking to daily life in Sudan, borrowing from the nation’s longstanding craft traditions and the Arabic script he had learned in his childhood, he began developing what he called a “pictorial alphabet” – essentially a fusion of abstraction and calligraphy. Works like Alphabet No. 1 (1960), which weaves sacred geometry and stylised creatures into a Modernist tapestry, exemplify this.

El-Salahi’s paintings, particularly from the 1960s and 70s, speak to the aspirations of newly independent African nations. “The common goal we pursued [with the Khartoum School] was to create a place for the artist in society, and to refresh and activate the visual and aesthetic memory of the Sudanese people,” he explains, “and from there approach the world at large.” Employed as Sudan’s Director of Culture, a distinguished position, from 1972 to 75, El-Salahi played a vital role in shaping the nation’s artistic identity.

However, his life and career took an unexpected and agonising turn in 1975, when he was imprisoned on false charges of conspiracy. In the harsh confines of Kober Prison, isolated with no access to art supplies, El-Salahi covertly drew on scraps of paper, burying them in the sand. “I would make a drawing, fold it, and then hide it under the sand of the cell floor,” he recounts. “At the time, it was all I could do. Drawing gave me strength.”

This painful period forced El-Salahi to reckon with, in a physical and visceral way, the political environment and its impact on artistic expression. Resulting in a disrupted and fragmented way of working, where each drawing was, as he puts it, an “embryo” of something larger, incarceration profoundly impacted his process and outlook on making work. “Working in a democracy is a lasting experience; working under a dictatorship is an incentive for doing something – sometimes you can be afraid of the consequences, but sometimes you have to say you have a definite message,” he told Art Review’s Mark Rappolt.

After his release in 1976, El-Salahi was exiled from Sudan, and eventually settled in Oxfordshire, England. Perhaps it was in part the influence of the British countryside that rekindled his exploration of trees. In his ongoing Tree series, spanning works on paper and various sculptures, the artist reinterprets the haraza tree, a defiant species of Acacia native to Sudan that blooms only in the dry season. For El-Salahi, the tree is a link between heaven and earth, the individual and the divine. “What I do now is like meditation. A kind of prayer,” he reflects.

Today, El-Salahi’s works are held in some of the most important collections around the world, including those of the Museum of Modern Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, Sharjah Art Foundation, Berlin’s Neue Nationalgalerie, and Tate, London. His 2013 retrospective at Tate Modern was the first solo show of an African artist at the institution, a historic moment solidifying his legacy. Now in his nineties, the artist remains a creative force, continuing to produce works instilled with a spirit of resilience and mysticism that inspires new generations.

References:

Art in Context Africa, Part V: Ibrahim El-Salahi, Mark Rappolt, ArtReview, 2015

Ibrahim El-Salahi, Nancy Dantas, La Biennale di Venezia, 2024

Ibrahim El-Salahi: A Visionary Modernist, Tate Modern, 2013

Ibrahim El-Salahi: At Home in the World – A Memoir, Salah M. Hassan, The Africa Institute and Skira Editore, 2022

Ibrahim El-Salahi: Frieze Sculpture – Meditation Tree, Vigo Gallery, 2022

Recent Acquisition: Major Acquisition in African Modernism, Perrin Lathrop, Princeton University Art Museum, 2023

Understood and Counted: A Conversation with Ibrahim El-Salahi, Sarah Dwider, Guggenheim Museum, 2019

Feature image: Ibrahim El-Salahi, Untitled, 1967. Tate. © Ibrahim El-Salahi