Vienna Through Performance: Opera, Actionism, SPARK Art Fair and Beyond

By Nadine KhalilMy encounters with the city of Vienna have always led me to performance, in a broad spectrum of this term. Over a decade ago, I was working for a men’s luxury magazine and I was invited to the opera ball, an annual event at the Vienna State Opera. Dancing debutantes, normally of upper-class heritage, waltzed in tiaras and white gloves, enacting highly choreographed gendered norms and social hierarchies. Writing about this form of aristocratic entertainment, a 19th-century residue of Habsburg rule during the Austro-Hungarian empire, felt like translating an unfamiliar code of imperial nostalgia. My second experience with Viennese culture was more contemporary, yet no less peculiar. In 2022 I witnessed an iteration of Hermann Nitsch’s 1957 6-day play by the Orgies Mysteries Theater at his Prinzendorf Castle in Lower Austria. It was my first time seeing Actionism live, of which the late Nitsch was a leading figure. Having moved into art criticism then, I wrote about the Dionysian happening, an exercise in emotional stamina that evoked pagan ritual through the blood and guts of animal sacrifice. I remember the sensory overload — food, wine, and orchestral music included. The play was a far cry from the high stakes of the past, yet a deep fascination with Vienna’s cultural contradictions kept luring me back.

When I visited again a year later, I learned that Actionism engendered other radical performance artists such as Valie Export whose Albertina museum retrospective documented solo exhibitionist practices that represented her break away from the movement’s male-dominated collective dramaturgy. The commercial scene also has plenty to offer in terms of performative practices, particularly by underrepresented women artists from Eastern Europe, many of whom were practicing in the 1970s at the same time as Marina Abramovic, yet whose works were not exported to global capitals in the same way.

At this year’s fourth edition of SPARK, a curated art fair of solo artist presentations which read like mini-exhibitions, there was a lot to explore in this vein. A case in point is 1 Mira Madrid gallery’s presentation of an early performance-video by Croatian pioneering performer Sanja Ivekovic, Instructions #1, 1976, where the artist drew, and gestured towards, arrows on her face to indicate either cosmetic care or surgery. Particularly evocative was Fear of My Own Hand, 1982, collages of the artist’s screaming portrait near silhouettes. More complex and at times abstruse were Ivan Gallery’s photo-documentations of Romanian artist Lia Perjovschi’s performances such as Test of Sleep, 1988, in which her body is covered with mythological symbols, as well as 1990s Mind Maps and recent paintings. In Alterego (I’m fighting for my right to be different), 1993, she douses a life-sized textile doll in black paint and performs aggressive acts on it. Perjovschi, who is married to the well-known political cartoonist and installation artist Dan Perjovschi, is finally achieving art world recognition for her critical pedagogy; she employs different languages in her practice as subversive tools against times of Communist repression.

At the Ewa Opalka Gallery booth on the other hand, Mariola Przyjemska, who is of Perjovschi’s generation, took a satirical approach to post-Communism in Poland with her painterly takes on consumerist branding. Her latest series, Victoria’s Secret, 2019-2020, features photographs of statues of Christ in Warsaw churches and museums, which, cropped and abstracted, focus on missing or masked genitalia that render gender ambiguous. Elsewhere, a standout sculpture entitled The Good Hope, 2021, by young Brazilian artist Selva de Carvalho at Karla Osorio’s booth took a more explicit approach: an erect phallus in charcoal and ash, barely visible against a black textile is clasped within a green, coiled serpent’s mouth. Red embroidery unspools in a piece of fabric on the floor like a puddle. Other textile pieces by the artist depicted gestural forms and creatures embroidered on womb-shaped fabrics. Meant to adorn or mask the figure, they are partly inspired by the artist’s dance practice.

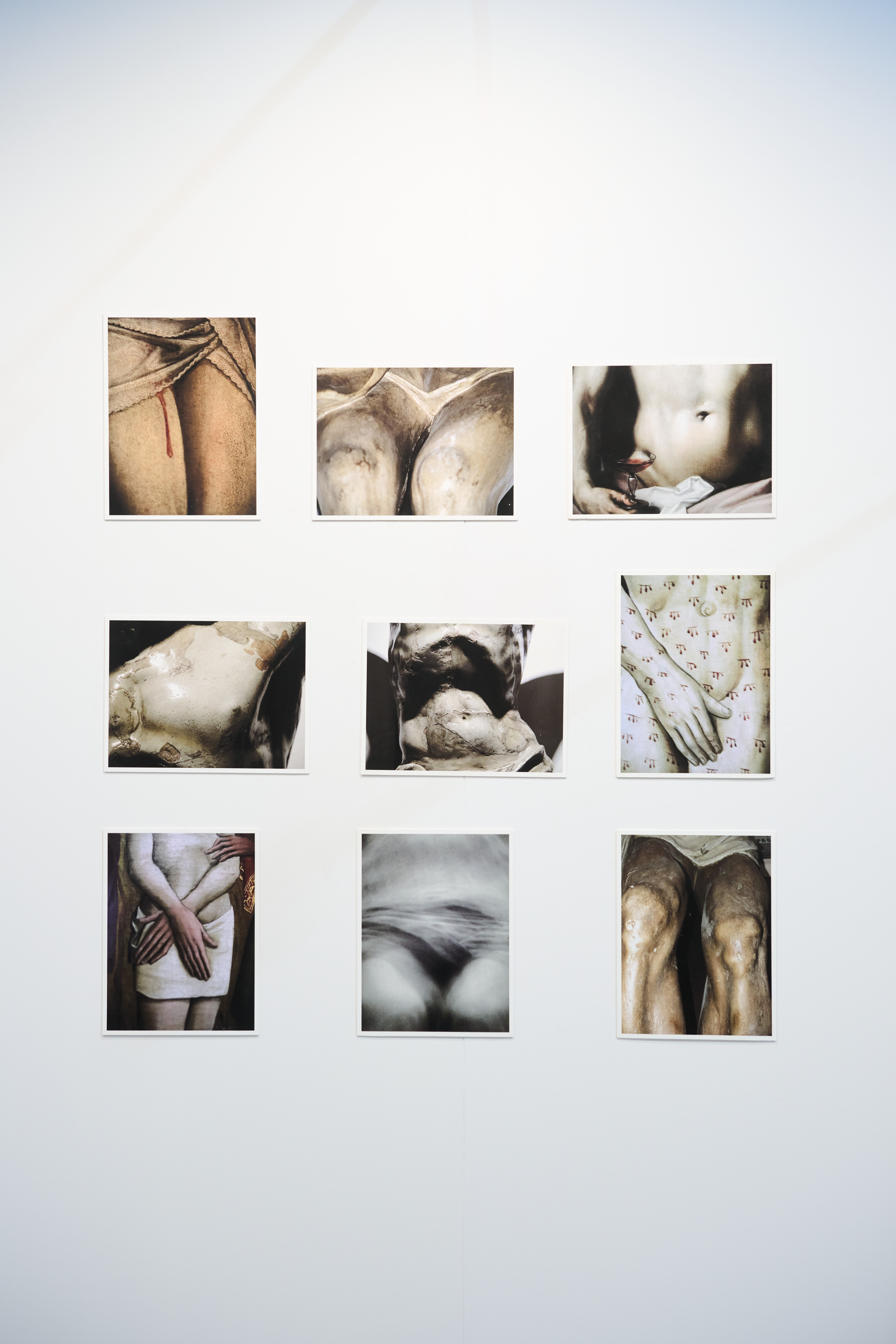

Another striking rendition of female body parts was Yasmina Assbane’s voluptuous, fluid forms made out of stacked plates in mesh stockings at Galerie Gisela Clemente — hard sculptures that look soft. The suite of small-format paintings by Ecuadorean-born artist Boris Torres, who captured voyeuristic moments of queer intimacy also charmed me at Kates-Ferri Projects in their exuberant, filmic vignettes.

It was exciting to see new work at the acb gallery booth by Selma Selman, a rising Romani artist from Bosnia and Herzegovina who I’ve been following since I witnessed her performance “You have no idea,” at the National Gallery of Kosovo during Manifesta14. I still remember how her repetition of this phrase over and over in a crescendo took traumatic, visceral proportions. At SPARK, acb showed her interpretive self-portraiture, overgrown fingers, and disembodied eyes painted on spare car parts, a reference to her family’s trade. On a car door, she painted a message to her alterego: “Dear Omer, it is so dark here that I want to burn something.”

Another materialist take on self-portraiture could be found at The Breeder gallery’s sleek display of Georgia Sagri’s experiments in scale and fragmentation. Working the no work, 2012, imprinted a digital copy of Sagri’s naked body in salmon-toned hanging garments with her private parts precisely positioned and sized. A part of a performative installation at the 2012 Whitney Biennial, the work looks at the opacity and disposability of the body in a comment on the wearability of social roles, machine-like labour extraction and self-objectification. Her 2018 Fresh Bruise series on vinyl prints are zoomed-in festering wounds akin to life-size explosions. Signifying marks of domestic violence and drawn from publicly available police reports, they become manipulated found objects. These were exhibited alongside a series of small (35x24cm) yet compelling unconscious drawings made from 2008 to 2012, depicting hybrid bodies and creature-like entanglements.

Dreamlike visions of animals or chimeras continued at Galerie Krinzinger’s booth with surreal watercolours by Lois Weinberger, an artist known for his work with natural environments, and mythical paintings by Iasonas Kampanis at Wilhelmina’s, a young dynamic gallery on Hydra island in Greece. Kampanis’ aesthetic has the childlike feel of folk art though it has academic inclinations. He mines ancient Mediterranean art and Hellenistic mosaics of leopards and apotropaic symbols to develop animistic visions in amplified hues of red, green and yellow, like thermal images seen through a night vision camera. His red masked eyes, Gaze, Gaze II, 2025 are inspired by 3500-year old eye idols from Syria – the natural world looking back at us — an impulse that echoed in Kiluanji Kia Henda’s phenomenal Eyes Without a Soul — Post-Industrial Portraits, 2024, at Galleria Fonti’s booth, a series of 24 portraits of a decommissioned thermal power station in Catalunya. Formerly shown at Barcelona’s 2024 Manifesta biennial, the morbid faces of this obsolete plant, comprising screws on decaying concrete, were unnerving when seen together, anthropomorphic witnesses of a toxicity which impacted an entire population.

The fact that SPARK’s team includes writers and publicists as well as independent collaborators such as Athens-based Marina Fokidis, former co-curator of documenta14 and founder of the journal South as a State of Mind, is perhaps why there’s such a felt understanding of the narratives shaping art world discourse even if quite Europe-focused. Among the 90 galleries featured, representation from the Global South was notably thin with the majority (60) based in Austria and Germany.

Although there was a disparity between how tightly curated the main entrance hall was curated (from which I’ve included all my picks) and the adjacent hall that had less contemporary work, the fair experience was a pleasurable one. It imparted a sense of spaciousness, generosity and context to each artist on show. Unlike other fairs of this size, I felt I could breeze through most of it in a day, which offered time to explore some fantastic museum shows outside, including YBA artist Jenny Saville’s first solo in Austria — a cross between excessive carnality and Byzantine-inspired transfiguration — at the Albertina, where there was also an astounding exhibition by Francesca Woodman from the local Verbund Collection of avant-garde feminist artists. Woodman (1958-1981), who died at the age of 22, performed for a black-and-white medium-format camera to represent her body in revelatory ways.

During my time in Vienna, there were rising concerns about the federal budget cuts due to the newly elected FPÖ-ÖVP government, which reduced the cultural funding by almost 50% in Styria, a regional hotbed of writers and composers, and which could impact Vienna in the near-future. Vienna boasts 95 independent art spaces, many of them artist-run and subsidized by the municipal government. On my last day, I experienced one of the recently opened ones, discotec. It showcased the performance Future Perfect III behind glass by the artist collective Club Fortuna (Xenia Lesniewski, Nana Mandl, Verena Preininger, Sarah Sternat) in art brut style with automated prams, sculptures and a fridge full of frozen eggs, while the audience watched the twerking, repetitive gestures and live breastfeeding from the street. Just a few nights before I was invited to a pop-up painting show, Blue Light, by Greek artist Aliki Paliou, who rendered the glow of the screen with tactility and resonance with dusk and natural light. Organized by Wilhelmina’s at another new space, Grill & Guests, founded by the artist Helmut Grill, the contrast between these two self-organized events exemplifies what I love most about Vienna, and why I keep returning.

Nadine Khalil is an independent art critic, editor and curator. She is currently researching the body as an expanded site of performance and labour. She is the former editor of Dubai-based contemporary art magazine, Canvas (2017-2020). Her writing can be found in Art Forum, The Art Newspaper, Art Review Asia, Brooklyn Rail, FT Arts, Frieze, Ocula and the Women’s Review of Books.

Feature image: Yasmina Assbane presented by Galerie Gisela Clemente. SPARK Art Fair 2025. Photo: © Kurt Prinz