After Representing Lebanon in Venice, Mounira Al Solh Brings Her Feminist Archaeology Home to Beirut

By Keshav AnandMounira Al Solh’s solo exhibition, Stray Salt, on view at Sfeir-Semler Gallery in Beirut until 1 August 2025, marks the artist’s homecoming after representing Lebanon at the 60th Venice Biennale. In Beirut’s downtown port district, a site fraught with history and trauma, Al Solh probes and rewrites the stories that have long defined women’s roles in national and mythological narratives.

“I frequently go to Tyre,” she tells me. “But after all of the tragedies we have experienced in the past few years – the Lebanese financial crisis, the Covid pandemic, the August 4 explosion at the Beirut port, and even the 2023 earthquake – my trip to Tyre triggered something new in me.” An early Phoenician metropolis and one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in the world, Tyre’s rich history, once peripheral in the artist’s consciousness, grew increasingly significant. “When I visited the fortress of Tyre, I discovered that while the tale of the Phoenician princess Europa is widely known among Tyreans, it is little known in other parts of Lebanon. So, my research started to become more focused, and my connection with this ancient history was getting stronger.”

Stray Salt picks up the thread of this myth, unspooling it across sculpture, painting, video, and textile works. Europa, who was abducted from Tyre by Zeus in the guise of a bull and carried across the sea to Crete, becomes in Al Solh’s hands a contemporary figure – no longer abducted, but self-determined. “I knew I wanted to address our Phoenician past… reimagining a mythical journey that has resonance in modern displacements,” she says, reflecting on the show’s origins.

In Sfeir-Semler Gallery’s front window stands a ceramic sculpture. Where the Lebanese Emigrant statue, installed in Beirut’s port in 2003, commemorates migration with a heroic male figure, Al Solh offers a proud, barefoot woman. “Being an emigrant myself, I often stop in front of this statue – even before the port blast,” she says. “Many women, like myself, had to move and travel to make a living. And after the August 4 explosion, the number of Lebanese that had to emigrate increased largely, including women who had to leave in order to support their families. They resemble this prototype, so I decided to create one for these women.”

In her version, the figure steps forward from a boat shaped like a murex shell – “the murex shell refers to our Phoenician roots,” she explains – pulling behind her a carry-on suitcase, a symbol of the modern migrant. Her body is nude and unapologetic. “The figure is in motion, emerging from the murex and travelling across the globe like the Lebanese diaspora,” Al Solh says. It’s a gesture of both ancestral continuity and defiant reinvention.

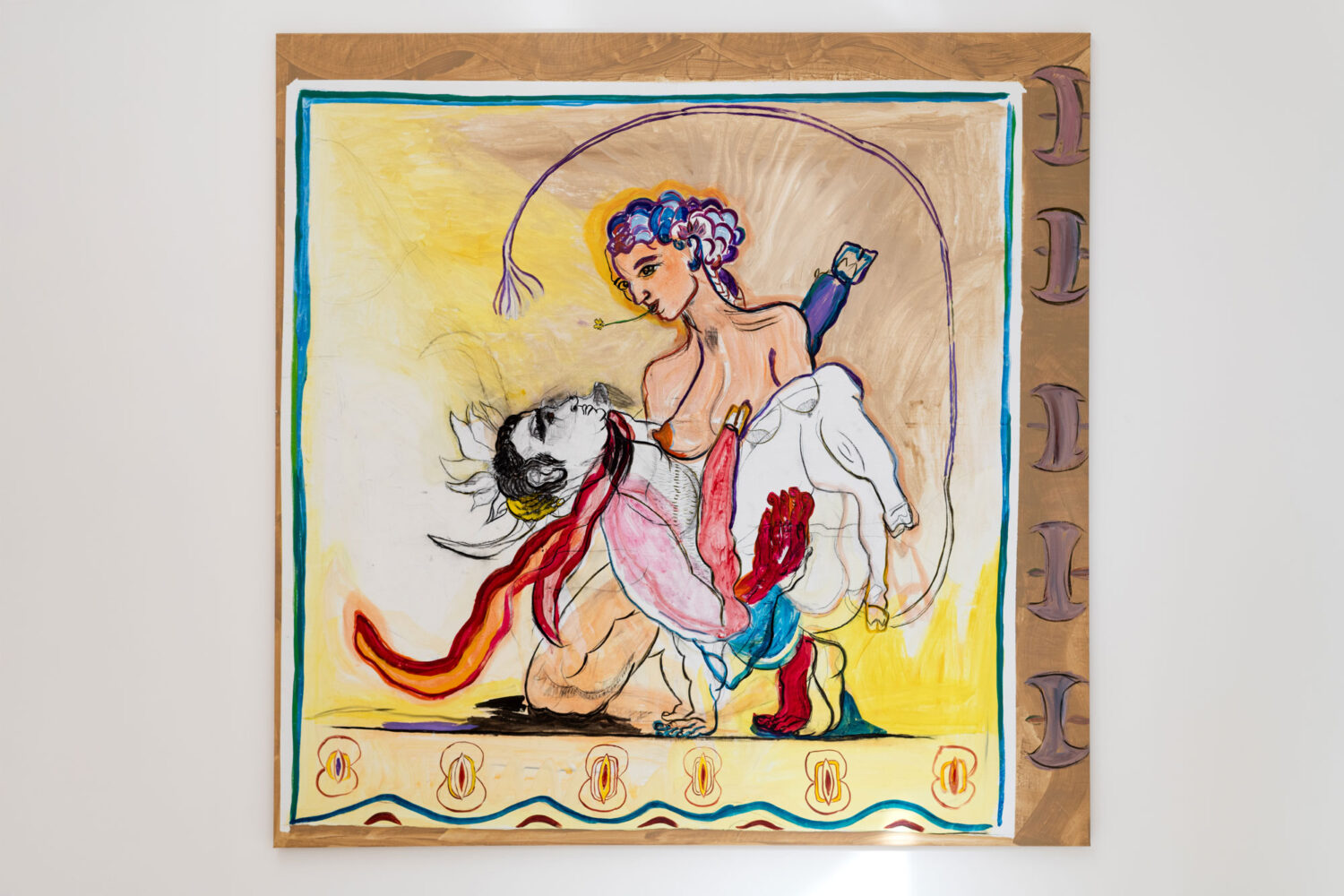

This fusion of antiquity and modernity runs through the rest of the exhibition, with mosaics and Phoenician inscriptions meeting acrylic and animation. In a series of large-scale paintings, Al Solh depicts Europa not as a victim but as a caretaker. “One shows Europa holding Zeus in her arms, while the other shows her holding him in a jar,” she says. “I wanted to negate the damsel in distress narrative.” Instead of abduction, there is intimacy, control, even containment. The bull, often a symbol of masculine dominance, is reframed as dependent.

Alongside Europa, Al Solh explores the lives of other mythological characters. “I am gradually moving into a new chapter, which is the story of Elissa, another Phoenician princess who also had to flee Tyre,” she shares. “We have a series of paintings depicting the women who joined Elissa’s tribe when she first reached Cyprus on her way to Tunis. We also have a series of portraits of Elissa’s people. The portraits are influenced by many eras – Phoenician, Roman, Byzantine, and Islamic periods.” This temporal layering reinforces the exhibition’s central insight that history is never fixed, but constantly rewritten by those living through it.

Elsewhere in the presentation is Two Airplanes and the Luggage, a new video work displayed on a television screen nestled within a wooden fishing boat. The animation shows Europa fleeing bombings, abandoning not only her suitcase but also the bull who once carried her to Crete. Accompanying the images is an uncanny, human-generated soundtrack: bird chirps, warplanes, and explosions, created using Al Solh’s voice. “I had a video projection at the Venice Biennale in which I also used my voice,” she explains. “Back then, just like now, I felt the need to generate all the content on my own. I didn’t want any artificial effect or technology to create the noises. So, I adopted the do-it-yourself approach, which felt more real.”

Voice, both literal and metaphorical, is central to Al Solh’s practice. Her work resists spectacle in favour of something more intimate, more embodied. That intimacy finds particular resonance in Beirut, a city Al Solh has long called home, even as her career has taken her around the world. “Lebanon is my ground zero and my source of inspiration,” she says. “Bringing part of the Biennale back home felt natural. It is where the story stems from.” The exhibition was initially delayed due to the war in Lebanon last year, but for Al Solh, its presence now carries deeper significance. “We were determined to make it happen as soon as the war calms down a little. Lebanon breathes through art, and this act of resilience embodies our attachment to this country and our will to never give up.”

Mounira Al Solh’s Stray Salt is on view at Sfeir-Semler Gallery, Beirut until 1 August 2025.

Feature image: Mounira Al Solh, Two Airplanes and the Luggage, 2025. Courtesy of the artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery Beirut/Hamburg.