“I Can’t Afford to be Boring”: A Conversation with Novelist Katharina Volckmer

By Bartolomeo SalaBorn in Germany but writing in English, Katharina Volckmer is one of a handful of female contemporary writers (another being Missouri Williams) who still loves to antagonise the reader and shatter a few taboos along the way. Her first novella The Appointment—published by Fitzcarraldo in 2020 and recently brought to the stage by Call My Agent’s star Camille Cottin in France—was a tour de force written in the vein of Thomas Bernhard’s Woodcutters (1984) and Philip Roth’s Portnoy’s Complaint (1972). (Suffice to say that the original title, maintained in the foreign editions, was A Jewish Cock.)

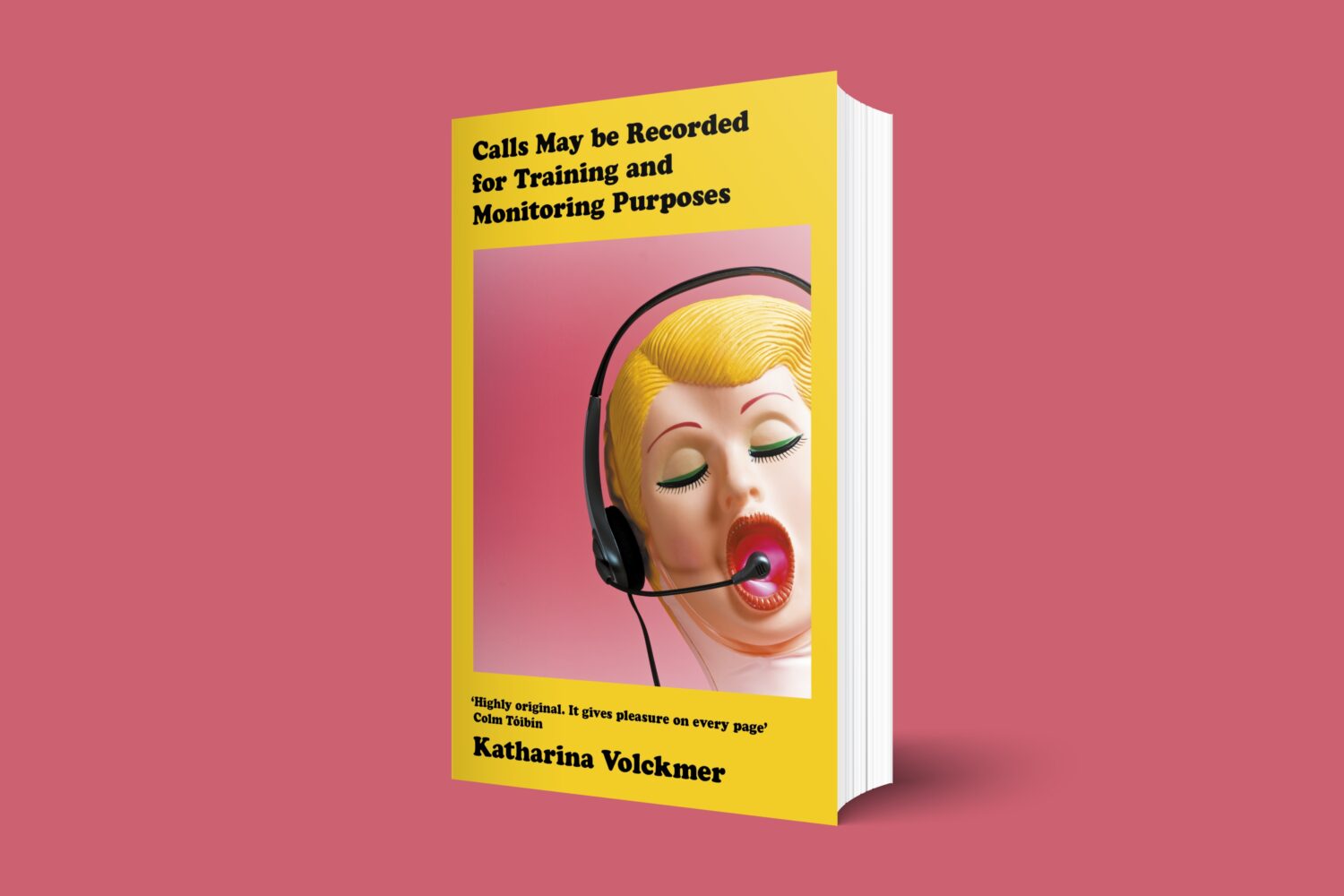

Her second book Calls May be Recorded for Training and Monitoring Purposes—published by Indigo Press in April—seems to pick up where the earlier book left off. In telling the story of Jimmie, an overweight, crossdressing call centre worker who could be plucked from an Almodóvar’s movie, however, it seems to strike a note altogether less angry, openly cutting, more heartfelt and emotional. Beyond all the provocations and boundary-pushing, at its heart this book is about love, and the human need for connection.

I have been friends with Katharina for a long time—since mustering some courage and reaching out to tell her how much I enjoyed The Appointment. So it was great to sit down with her new book and hear about the inspirations for the book, why she writes about characters that defy gender categories, and how it felt to grow up in 1990s Germany at the height of the telephone sex craze.

Bartolomeo Sala: In many ways, Calls May be Recorded seems to follow in the footsteps of your debut. For one, you have the protagonist Jimmie who, like the anonymous narrator of The Appointment, is someone who is ill at ease in his body. Lots of the humour and knack for provocation are also similar.

At the same time, it is impossible not to notice a new tenderness surfacing. I am thinking of the scene in the bathroom when Teresa puts lipstick on Jimmie, but also the sections that Jimmie shares with his love interest and co-worker, Daniel.

In what way is this new book a follow-up to your debut? And in what way is it a departure? Was there something specific you had in mind when writing it?

Katharina Volckmer: Well, I think I wanted to do something that’s different because for me it’s quite easy to write the voice that you have in The Appointment. That’s also why it’s a third-person narrative. Maybe I was less angry when I wrote it. I’m still angry, but maybe I was less angry when I wrote it because it’s a bit more tender and a bit more, I guess, focused on…

BS: Romance, or a lack thereof?

KV: Lack thereof, but also about work.

In a way, it’s about how our daily life makes us unhappy and sick, and how we’re often stuck in these situations. I think I’m quite interested in how work could be changed into something less invasive and less depressing.

But yeah, I think it would have been quite easy to write another angry monologue, but then I thought that it would be boring. And also, this is really stupid, but I think you might be able to relate to that because you are a foreigner as well. English is not my first language. And I was always afraid of writing dialogue because I thought as a foreigner that would be much harder. But then I thought, I’ll give that a go and think it worked quite well, actually. I have overcome the mental block now.

So yes, learning how to write dialogue is something that I had in mind when writing the book. Another was the idea of loneliness…

BS: I am glad you mention work and loneliness so early.

I have read the book twice. The first time I remember being struck by how well the book captured the sheer indignity of working in a call centre—the precarity of such a zero-hour service job, where getting fired is always a looming, implicit threat, but also the absolute pointlessness of it. On my second reading—maybe because I rewatched Paris, Texas in the meantime—what I picked up on more strongly was the loneliness these characters experience—Jimmie and the other misfits who are forced to spend their life in these small cubicles, of course, but also the vacationers who phone in on a Friday night in June because they don’t have anything better to do. At some point, I think Jimmie goes so far as to compare himself to a “saintly whore … giving generous relief to broken people in melancholy circumstances.”

As someone who actually had to work in an actual call centre—I don’t know if you consider the book autobiographical in any way—to what extent do you think this space works as a metaphor of the world we live in, the type of work we perform but also the kind of very digital lives we lead?

KV: In a way, I think the call center in the novel is like a cage. People are very isolated there. But at the same time, you have these sudden moments of intimacy.

I think as a society, we’re also struggling with intimacy a lot. I think being intimate with someone is something that seems to have become more difficult than being sexual. I don’t know if you agree. It’s real intimacy, I think, that a lot of people are struggling to allow for or to find. Also—you are a bit younger than me, but you’ll remember—in Germany in the ‘90s telephone sex was huge! You couldn’t go to a telephone booth without seeing all the stickers. And on TV, after a certain hour, they would advertise telephone sex. And in a way, it’s an homage to that as well.

So what I am interested in is this special kind of intimacy that you have on the telephone without knowing who the other person is. You can’t see them. It’s just the voice. At bottom, I think the call center is a metaphor about finding some way to communicate somewhere out of loneliness, to find intimacy again. Because loneliness, I think, is one of our biggest social problems. It’s something that fascinates me endlessly. We live in London, 12 million people, but people are desperately lonely. And they try to find a way out of their loneliness in all sorts of ways—online or otherwise.

You know you could call your toilet paper, right? Your toilet paper will have a number at the back that you can call. I’m like, who does that?

BS: No, I didn’t know that, actually.

KV: Any product that you take, there’ll be some way of contacting a customer service line and talking to people. When I worked in call centers, you really learn a lot about how desperate people are and how lonely. I mean, people would ask me out on dates and would use any excuse for you to keep on talking. The most sad calls in this book are based on real phone calls… And then there is this culture of complaining.

BS: Can’t say I am not guilty of that.

KV: But it’s by design. There is a number you can call for TFL [Transport for London] that’s only for complaints. Can you imagine that? There are people who spend eight hours a day listening to complaints. These people have become lighting rods or emotional punching balls. You wouldn’t do that in a shop, you wouldn’t walk into a shop and start yelling at the shop people.

BS: This brings me to something I wanted to ask later—this idea of performance, of putting up an act, as a sort of safety valve or escape route from the sorry reality of one’s existence. The circumstances of Jimmie as a middle-aged gay man with mommy issues and a zero-hour contract are objectively very grim, but he is able to overcome them by means of fantasy…

KV: At the same, there is the performance of being at work. I think there are studies about how much work influences and shapes who you are. There are certain jobs that dictate how to dress, that dictate how you speak, the language you are going to use, your manners. I remember I had a friend who worked in some French shop, she had to wear makeup every day. When I was young I worked at Burger King and remember you had to wear a uniform, which is totally humiliating and erases all the individuality you ever thought you possessed.

To this extent, I think work can be very violent. You become your work. So the book asks the question implicitly of what would happen if you suddenly stopped to comply? In real life, you would get fired of course, but what if there was another way to go about it?

BS: Call May be Recorded takes the shape quite obviously of a workplace comedy. Although the humour is not British at all, lots of the situations and characters seem to be plucked out directly from The Office or The Thick of It.

At the same time, Jimmie is a character straight out of camp, over-the-top queer melodrama. I am thinking of Almodóvar’s Talk to Me or Fassbinder’s The Bitter Tears of Petra Von Kant. Did you have this stuff in the back of your mind, or did it come to you organically?

KV: I think it’s organic, but those two, Almodóvar and Fassbinder, are definitely, I think, influences. I loved Fassbinder when I was younger. The thing I love about Fassbinder is that he would often use these totally random people. But also, I think he found a lot of beauty in things that other people consider ugly. I like doing that as well. I had journalists ask me, “Oh, but can this topic ever be literary?” I just thought, Fuck off. I think anything can be.

BS: It’s the idea of camp, the idea of appropriating what’s lowbrow into highbrow…

KV: It’s about creating your own aesthetics, totally independent of what’s actually fashionable or beautiful. It’s the same for Jimmie as well. He could never be considered beautiful according to today’s beauty standards. He will never feature in a movie unless, that is, it’s a Fassbinder movie. Same with Almodóvar’s films—I always loved the weirdness of it, the total confidence in the sheer weirdness of it. But also how radical and modern he was, and how he picked up on topics 30 years before anyone else did. The way he talks about queerness, HIV, and Spanish history. That’s quite radical, or at least it used to be.

Neither of them are really afraid of taboos.

BS: In a conversation with fellow novelist Eliza Clark from a few years ago, you talked about art as a sort of “ice pick”, a jolt to the system that should shock someone out of complacency which in the image you give is represented, very funnily, by “drinking tea whilst wearing wooly socks”.

Like The Appointment, Calls May be Recorded is full of scenes and sections that shatter taboos and challenge opinions just for the hell of it. Rather than openly confrontational, the sentiment of the book seems to me carnivalesque in the old sense of trying to upend all of societies’ structures and strictures. Jimmie, who I think importantly dabbles as a clown, is a catalyst for all sorts of mischief and repressed desire as well as a character who both challenges not just heteronormativity but office etiquette as well. This approach seems to me to go against the grain of much contemporary literature which honestly often seems hopelessly straight and self-serious.

What’s the role of provocation in literature? Is there still value in trying to outrage the bourgeois, or is this even ultimately a chimera?

KV: I think at this moment, we can’t afford to become boring. I think it’s very dangerous when culture suddenly becomes dull. But a lot of it, unfortunately, has become boring and very mainstream. I think it is ultimately very dictated by what makes money and by who funds culture. I think people are increasingly afraid of each other, almost. They’re afraid of being canceled. They’re afraid of scandals. Well, I would have thought a scandal could be something fantastic.

I don’t know if you know of Heldenplatz by Thomas Bernhardt, which was the biggest theater scandal in postwar Austria. That’s great. I don’t know why people are so afraid of controversy, of disagreements. I hate these events where you are put on a stage with someone who has exactly the same opinions as you, and then you congratulate each other on having these really forward thinking opinions about the world. I would love to argue more with people, and I think we’ve almost forgotten how to do that.

We think we are beyond taboo, but we are not at all. If anything, we’re moving back to that. I think no problem goes away if you stop talking about it. I think there are a lot of things that we now don’t talk about anymore because it’s become too complicated. But that doesn’t necessarily make anything better. I think people on the right must be having a laugh seeing us tearing each other apart over the smallest, most ridiculous stuff when instead we should come together against the common enemy and the problems we face.

BS: You know how much I agree with you on this.

KV: And then all of this is compounded by books having become pretty accessories, which are judged less by their content than as the expression of the social profile of the creator. I find that so boring.

BS: I think it would be reductive to define the anonymous narrator of The Appointment and Jimmie as trans. At the same time, there is no doubt that both characters are defined by the fact they don’t quite fit into neat categories, all the while unsettling or troubling gender and sexual norms. Theirs are bodies and subjectivities that simply won’t conform to certain standards, be they aesthetic or moral. Why do you seem attracted to this topic?

And secondly—in the light of the recent debacle regarding trans women being denied their identity by a supreme court ruling, which defines a woman according to her biological sex in the UK—why do you think certain people, not just reactionaries, are so caught up in reductive binarism and therefore hellbent on regimenting this fundamental aspect of people’s lives? Have you formed any sort of thesis or viewpoint on this?

KV: I have. I think, first of all, bodies are incredibly powerful. If everyone realised how much power their own body has, we would be a lot farther than we are. What I like about the trans body is the body you build yourself in a way. That’s how I like to think of trans bodies, or what’s so powerful about them. It’s like someone saying, ‘Look, I might have been born like this, but I want to recreate my body according to my own ideas, obviously with certain limits attached.’ I think that is something very powerful, and I think that the hysteria surrounding the subject is precisely about that. These bodies are out of control in the sense that they are out of people’s control.

I think that in many ways gender is a social construction. We perform gender, so I like [to create] characters who take a little step back and think, what if I stop doing this? What if I stop performing gender in that way? I think people are just terrified because they use it as a way to make sense of the world. And also there is the fact that this binary system allows for the oppression of everyone who’s not a straight male. What would it mean to relinquish that? I think it’s a fear of a loss of power or loss of control over people, which also applies to beauty standards.

As to this court ruling, I think it’s just absurd. It’s trying to force a reality onto people and their bodies that just isn’t true. I find it so sad. These people are popping their champagne bottles because they defeated a minority. It’s all part of a long history of queer bodies and people wanting to isolate them, separate them, and have special wards for them. The same with homosexuality—I think it’s fear and control and not letting go of certain fixed ideas of health, bodies, all of that.

BS: So you come to these characters because they seem better equipped to question structures that oppress you as a woman like the patriarchy rather than, say, identification?

KV: Yes, and also I think in the current debate, often people make it look like there are trans people and there are so-called cis people, and that’s all there is. But I think it’s a spectrum. There are a million things on that spectrum. I think that’s precisely what people are afraid of.

Bartolomeo Sala is a writer and reader based in London. His writing has appeared in Frieze, Vittles, and The Brooklyn Rail. Read more of Bart’s writing for Something Curated here.

Header photograph by Robin Christian ©.