Nick Knight: Photographer, Activist, Fashion’s Proctor and Mentor

The perennial influence of Nick Knight is tough to contain, or even identify. It’s at once everywhere and nowhere, stretching over 40 years of evolutions in the world of fashion photography, where he has consistently carved out trends and pioneered new status quos, while wearing the same levi’s 505s, white shirt, and Trickers’ brouges the whole time. Knight’s legacy has, in some sense, become inseparable from both fashion photography and the industry at large; his revolutionary ideas effectively becoming the operating mechanisms in today’s fashion world. Its prowess on the digital platform, for example, owes its origins to Knight’s push for a web-based, real-time exposure for high fashion through video format, a challenge he ignited at the turn of the millennium with SHOWstudio. Knight has also put pressure on the fashion industry to be held accountable to the massive issues of social inequality it had previously hosted without resistance. Knight has advanced both the industry and its discontents, a claim which few leading names of the fashion world can hold.

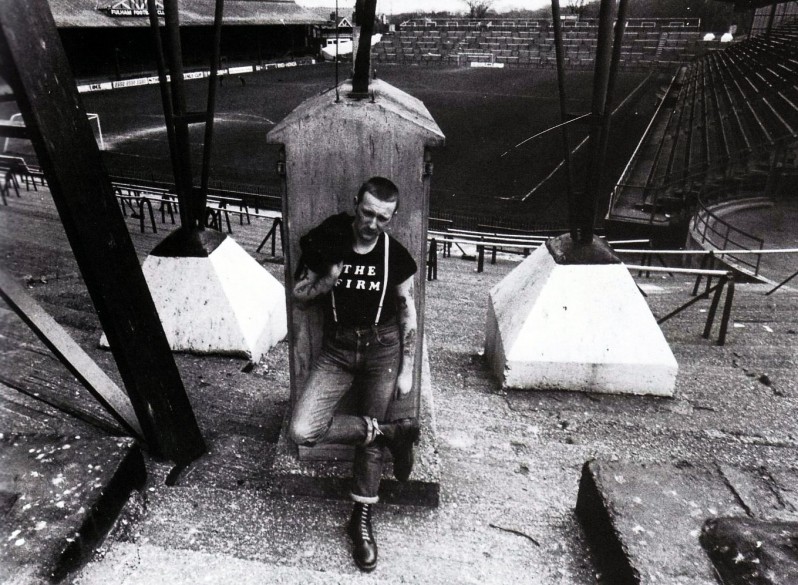

Knight’s first photography book, Skinheads, was published during in his collegiate years at the Bournemouth and Poole School of Art and Design. Through the sanguine, gritty black-and-white portraits of the urban subculture, Knight established his signature hot-cool feel; a marriage of rawness and sophistication, both ahead of the curve yet already, somehow, having a classical confidence and poise, as if he had been doing it that way for years. Though hard to argue that the analogue world of the 80s holds much weight in today’s digital fashion world, the latter owes its foundation to the tiny conceptual threads that Knight pierced through all of the polaroids and neon tracksuits. Although his images were just that—stills—they held a vibrant, humming energy, a certain liveliness which contemporary eyes reserve mostly for moving images. As technology advanced, Knight would soon make a habit of injecting these developments into the fashion industry almost as quickly as they premiered—effectively bucking the trend of timelessness and exclusivity in favour of accessibility and adaptability.

With the debut of Skinheads, Knight caught the attention of i-D editor Terry Jones while the magazine was reaching its heyday. From there he was picked up by art director Marc Ascoli, who commissioned the young photographer for 12 consecutive issues. But Knight’s ambition could hardly find satisfaction with a single genre or medium; he was introducing something not yet identifiable but unmistakably game-changing to the world of commercial photography. Knight was taking risks that nobody else would; frontier-trotting with finesse became his signature style. It wasn’t long until his clientele dilated to fit the likes of Mercedes-Benz and the Royal Opera House as well as Alexander McQueen and Dior. Pushing past the boundaries of still photography, Knight directed his first music video for Bjork in 2000—but not before initiating a push for a radical realignment within the industry’s reigning hierarchies and its ways and whos of seeing: in collaboration with art director Pete Saville in 2001, Knight launched SHOWstudio.com, a virtual gallery and interactive studio/workspace for those in the industry, accessible by the general public. Moving from Bjork to Lady Gaga, Elvis Costello to David Bowie, and most recently Kanye West, it’s easy to get lost in the spotlight of Knight’s portfolio—it never shuts off—especially when every project feels micro-revolutionary in turn.

Launching SHOWstudio was, in many ways, a call for transparency — a way of seeing but also of being seen. The website was meant to crack open what was up until a very short time ago an incredibly exclusive world, one shrouded in checkpoints of class, privilege, and connections. The whole process of creation and development within the industry was kept in the dark, with only its final form, the purchasable commodity, made accessible to the general public. Knight intended to disband that secrecy by inventing a space that was less concerned with polished, glossy surfaces and more interested in encouraging and exhibiting the process, opening up a space for lots of collaborative and hypothetical tracework—not simply the final stroke.

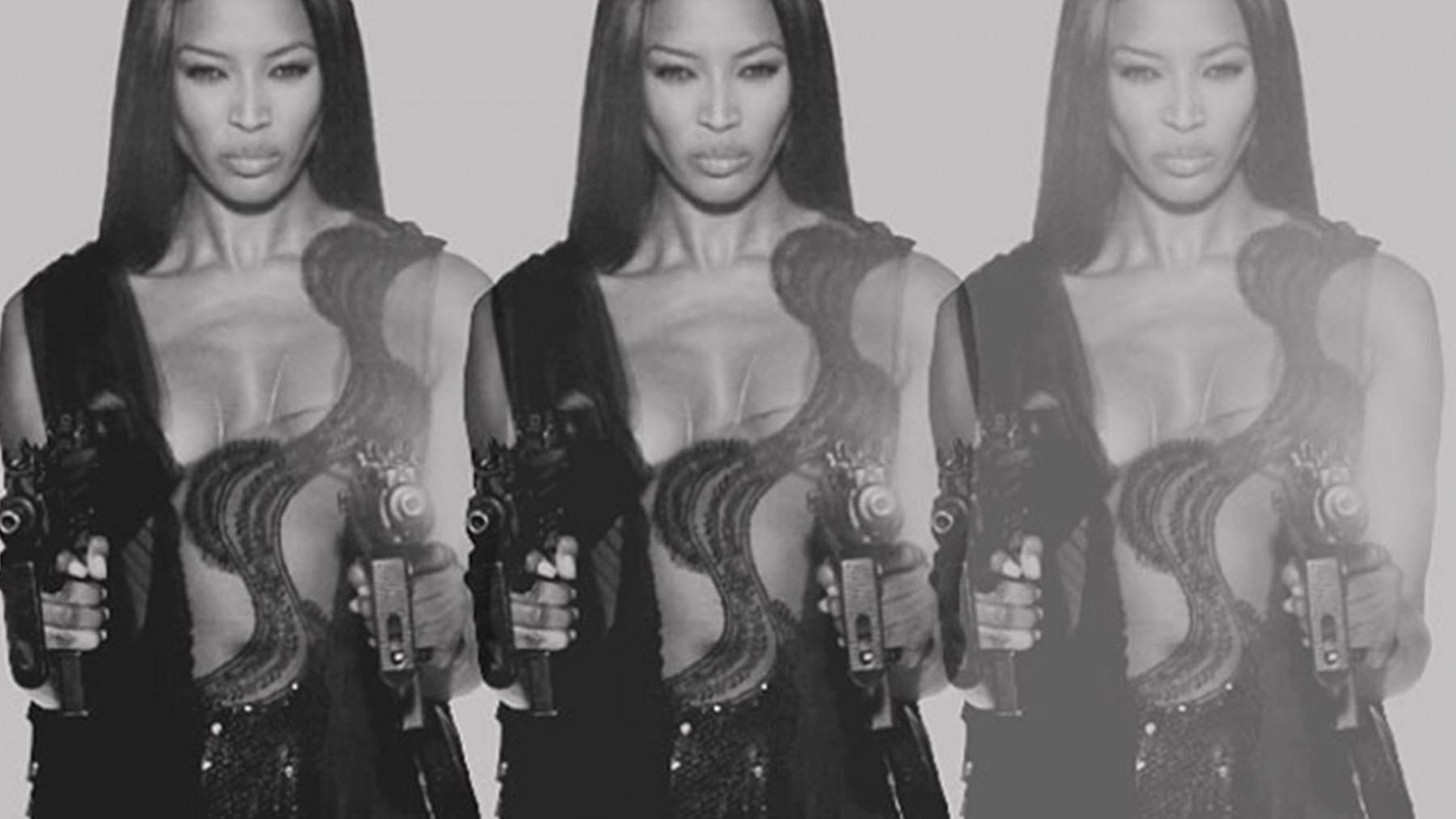

The site also allowed the art form to breathe easy in its natural state of being: in motion. ‘The strongest element of fashion photography has always been movement,’ says Knight. ‘If you look at someone like Richard Avedon, there’s a feeling of energy and life in the work, and that’s what I’ve always tried to do. I want it to feel like it’s bursting off the page. Film was an obvious thing to happen after photography, because if you have a medium that can distribute moving fashion, that’s what people will want.” By positioning the wearability of clothing—or how it appears upon a body, rather than flattened out into a sleek and highly aestheticized 2D image—at the forefront of the discussion by streaming fashion shows live, Knight not only opened up an immediate vantage point to the average spectator but he also, in a way, reoriented the industry back to its roots of real-space, real-time bodies in motion. He liberated the medium of the moving image from its previously subordinate and speculative status. Fashion was now forced to occupy the present and to be held accountable for present-day issues, like class, racism, and other inequalities that it both produced and sustained. In a 2008 collaboration with model Naomi Campbell, Knight produced a stunning video work, part manifesto and part dramatization, addressing with stinging criticism the massive under-representation of models of colour in the industry and its weighty ethical and social consequences.

ON THE FUTURE OF PHOTOGRAPHY:

“I think photography has already fallen into anachronism – photography is past. The parameters have shifted, and there is nothing that I do that is defined by the parameters of photography.”

“There’s a term called ‘generalism’, which is really applicable in these current times. If someone asks me what I do, they would expect me to say photography, but I’m not going to say that. Being a photographer doesn’t take into account that I make films, create sculptures and a whole range of other things that just aren’t photography.”

“Film died some years ago. I don’t miss it. None of my children read magazines. Fashion will be shaped by the internet.”

“Having a phone and an Instagram account means that I can create images on my own. When I first started using it a couple of years ago, it reminded me of the 70s, when I first started out in photography. It felt very direct – it was about me taking the image. I also really enjoy the instantaneous nature of it – you can publish images straight away – and get feedback from people across the globe… And I’m really interested in figures who have huge followings – such as Kim Kardashian, Cara Delevingne and Lily Allen…. It’s almost like when magazines were in their heyday – a printed publication would be where you could get celebrity images. Now it’s been reversed and the next generation is one that is used to getting information from digital mediums.”

ON MOTION:

“Clothes are designed to be seen in movement. One could argue that a still photograph of a piece of clothing is to some degree a compromise of the designer’s original vision. It’s also allowing people in. One of the biggest luxuries we have left is access.”

ON SECRET SPOTS IN LONDON:

St Pauls’ Artist Studios, Talgarth Road

“This set of artists’ studios that I pass everyday on the way to and from work, was built by Frederick Wheeler in 1890 and is where the wonderful Pre Raphaelite painter Edward Burne Jones, among others, painted. I have always loved the idea of a community of artists and this was my original motivation to start SHOWstudio.”

Train tracks at Old Oak Common Lane, Willesden

Nick says: “I drive past this on my way to the photographic studio. It is one of the hills in London that people seldom recognise but from the top the view out towards London across all the train tracks is a beautiful, still evocation of the industry of our city. These lines of communication give me a real world visual of how I imagine the internet.”