Navigating The British Film Industry: Key Figures To Know

By Something CuratedAside from the occasional blockbuster, the UK has held a somewhat understated position on the global cinema scene. Despite this, The London Film Festival expands year on year, now starting to attract some major international releases. Across the calendar, homegrown success stories have become more frequent. Below is a whistle-stop tour of some of the figures who have made big waves in recent times.

Documentary

Louis Theroux remains the poster child of British documentary making. His BBC specials quickly attracted a strong cult following in the late 90’s, before growing into full-out newsworthy events in recent years. Following the lead of older English filmmakers, such as Nick Broomfield, Louise approached his topics in the manner of a gonzo journalist. Injecting himself into the narrative and actively participating in his subjects, he effectively reinvigorated the format, showing its potential to be fun and insouciant, rather than laboriously informative. Recently, his focus has shifted from fringe, esoteric topics to weightier social issues. 2016 saw his first major box office release as he attempted to expose Scientology (ultimately, offering a light-hearted counterpoint to Going Clear, also released that year). Rumour has it that he now has his sights set on Donald Trump for his next major project.

Those with an appetite for the experimental will be drawn to Adam Curtis’ politically charged body of work. Making heavy use of collage and archival footage, Adam explores the power dynamics between elite minorities and those they ideologically oppress. His narratives are elliptical, ambiguous, making intellectual demands on the viewer and leaving them with few neat conclusions.

Behind the scenes, Simon Chinn is the man to watch. A powerhouse producer with two Academy Awards under his belt, Simon has been involved in some of the most memorable (and, often, commercially successful) UK releases. His films frequently focus on lone-wolf eccentrics. Man on Wire gave us rare access to Philippe Petite, a tight rope fanatic who walked across the Twin Towers in 1974; Searching for Sugar Man uncovered the bizarre story of Sixto Rodriguez, long presumed dead by a country that idolised him.

Drama

The U.K. was one of the original pioneers of kitchen sink drama (1950’s) and in-yer-face theatre (1990’s), genres that gave serious exploration to social struggles and issues of class. While these movements were predominantly confined to theatre, they left a long legacy which continues to shape and influence filmmaking. Ken Loach and Shane Meadows eschew Hollywood-style escapism, for more sober meditations on class. Although differing wildly in approach, both filmmakers use cinema as a space to reflect on the broad disparity of privilege across the U.K. and how this intimately shapes personal narratives.

Mike Leigh also tends to gravitate towards working-class narratives and characters. He deserves special mention for reconsidering the very role of filmmaker, ditching scripted drama for a more collaborative approach. Often working with the same cast of actors, he develops his films through an organic process of workshopping and improvisation, giving the final piece a deeply naturalistic quality. While he has helmed some more conventional (and bigger budget) dramas (Topsy Turvy, Mr. Turner) he’s gained a reputation for quiet, well observed character studies.

In a similar vein, Andrea Arnold is noted for offering hugely nuanced character portrayals. Early work, such as Fish Tank, gave an uncompromising view of life on the wrong side of the tracks. Like our previous auteurs, she tends to focus on characters from poor or troubled backgrounds, contributing to a distinct variety of gritty realism. Conversely, Joanna Hogg applies her attention to the languishing middle classes. Her debut, Unrelated, galvanised critics, with its devastating portrayal of affluent protagonists struggling through mid life crises. Her work consistently remains under-the-radar, but continues to go from strength to strength.

Veering away from politics, U.K. thrillers offer an object lesson in resourcefulness. While many filmmakers lack the funding for Hollywood style special effects, they’ve developed more creative strategies for ramping up tension. Steven Knight (who also writes for hit TV show, Peaky Blinders) took a more conceptual approach to the genre. His hit, Locke, offered a taut, psychological thriller of epic proportions, all set in the space of a single car ride. More recently, David Farr’s eerie drama, The Ones Below, plugged into urban unease and parental anxieties while drawing on a limited cast and setting his story largely in the confines of two flats.

The Dark Side…

British cinema has a strong fascination with the macabre; Peter Greenaway’s 80’s cult classic, The Cook, The Thief, His Wife and Her Lover setting a high-watermark for this category. No list would be complete without glancing at some of our more twisted contributions to the cannon.

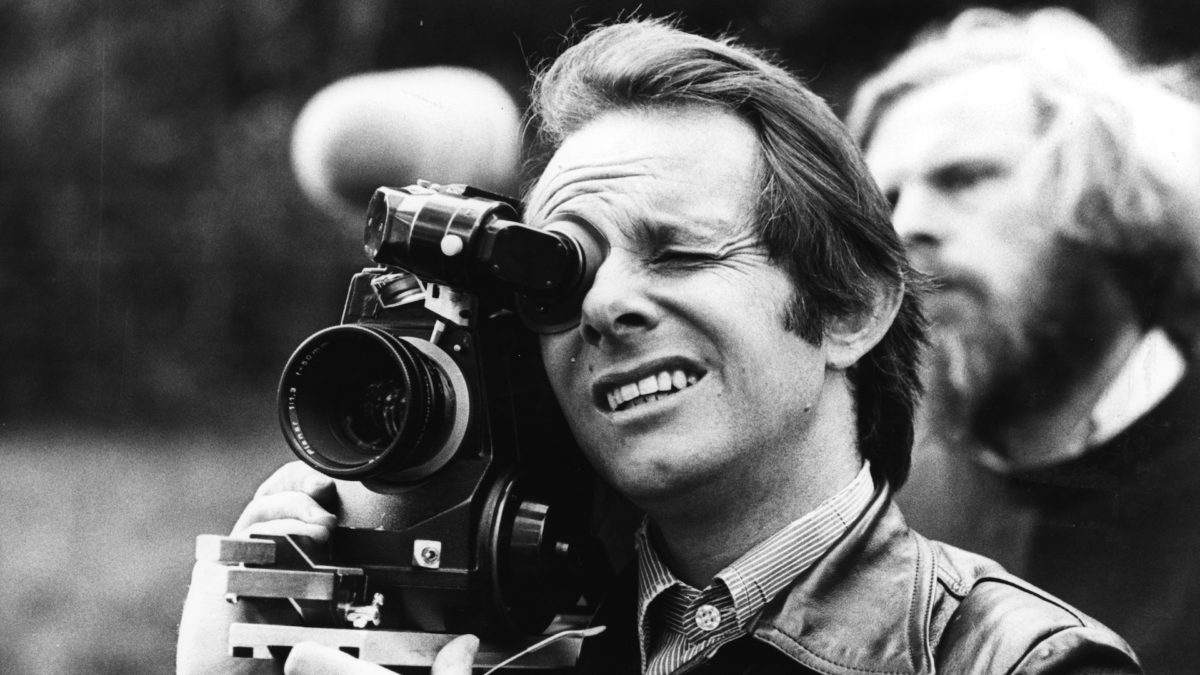

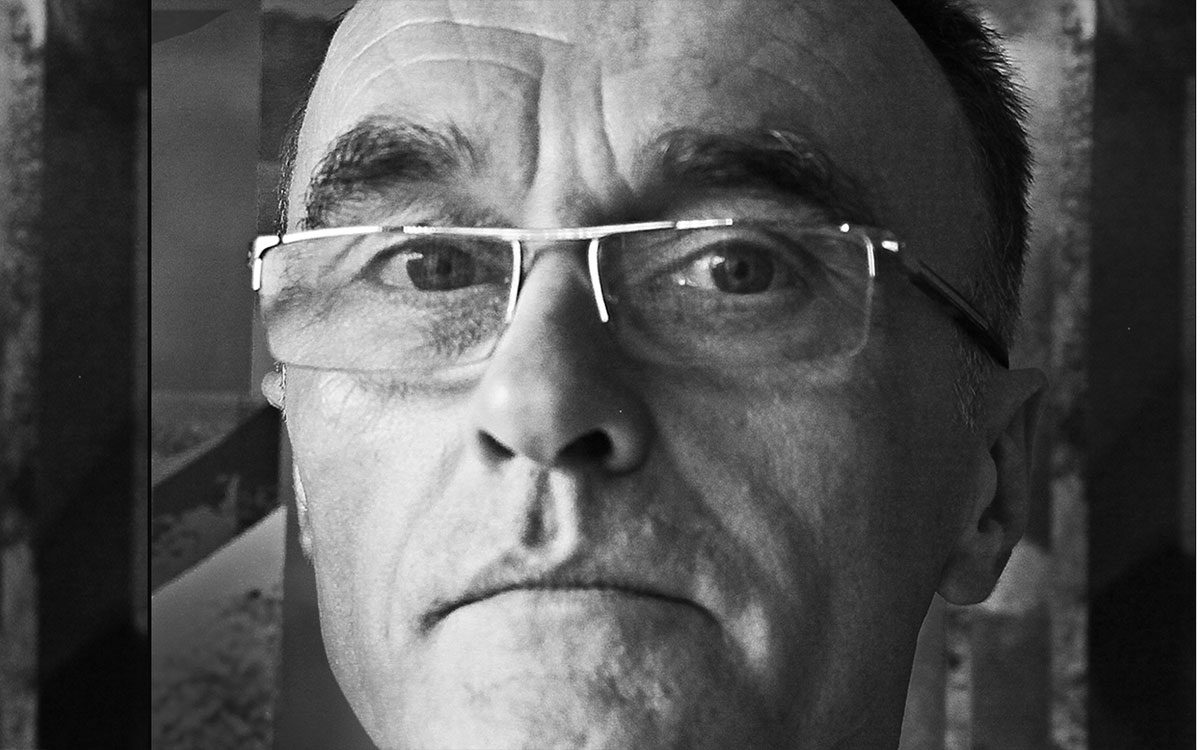

In 2002, Danny Boyle reasserted the UK’s reputation for horror. 28 Days Later offered a unique take on a tired genre, substituting relentless gore with eerily beautiful shots of a devastated city. Recently, Colm McCarthy (who’s more noted for his work in TV) has built on this legacy. The Girl With All The Gifts is a thoughtful and highly unconventional take on the zombie thriller, managing to reflect on evolution and our role on the planet while also serving up a healthy dose of shocks.

Of course, some of the UK’s comedies are black enough to flirt with horror. Ben Wheatley’s early films featured sociopathic serial killers as their protagonists (Sightseers) as well as hitmen and pagan cults (The Kill List). In 2015, he turned to J.G. Ballard for source material, directing High Rise; it felt like a true marriage of minds.

Similarly, writer Martin McDonagh also deserves mention for pushing the boundaries of deadpan comedy. He began his career writing for stage, producing scripts of such gothic horror, the world took note. His screenplays (In Bruges, Seven Psychopaths) are slightly dialled down, but have a stylised, intricately wrought quality that reflects his early work with the theatre. Like Wheatley, he swaps out obvious gags and punchlines for guns and brutal killings.

Over the past few years, we’ve seen a series of art-house releases with strong gothic elements. Carol Morley’s The Falling looks at a mysterious fainting epidemic amongst schoolgirls; The Wolfe Brothers’ Catch Me Daddy was touted as a ‘modern day Western’, though just quite what it was remains up for debate. Both manage to powerfully defy genre conventions.

Words by Sean Gilbert