Interview: Ziba Ardalan, Director & Curator Of Parasol Unit

By Something CuratedEstablished in 2004 by Art Historian and Curator Dr. Ziba Ardalan, Parasol unit foundation for contemporary art is a non-profit art institution housed within a converted Victorian furniture factory in London’s East End. Critical to the initiative’s ethos is a commitment to artists and their creative endeavour. Recognised for its progressive and challenging programme, Parasol unit has introduced a host of international talent to London’s public and has been instrumental in launching the careers of artists such as Michaël Borremans, Yang Fudong and Charles Avery. Something Curated met with Dr. Ardalan at the institution’s Wharf Road site to learn more about Parasol unit, upcoming projects, and her fascinating journey into this field.

Something Curated: Could you tell us about Parasol unit, the vision and ethos behind the organisation?

Ziba Ardalan: Parasol unit functions like a European Kunsthalle, which essentially means reacting to the artistic activities of its time. It is about content, and contributing to public education; it is not about visitor numbers, PR, or doubling its footprint.

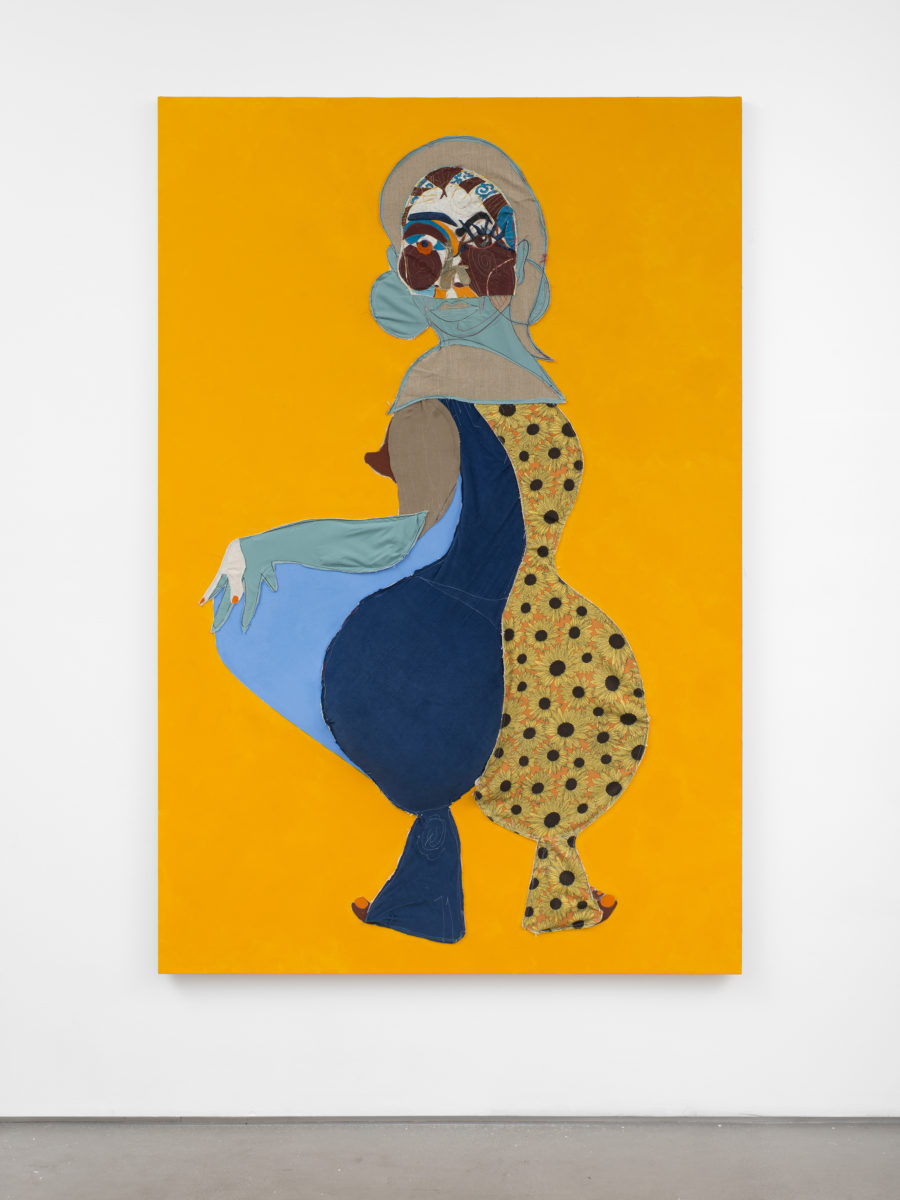

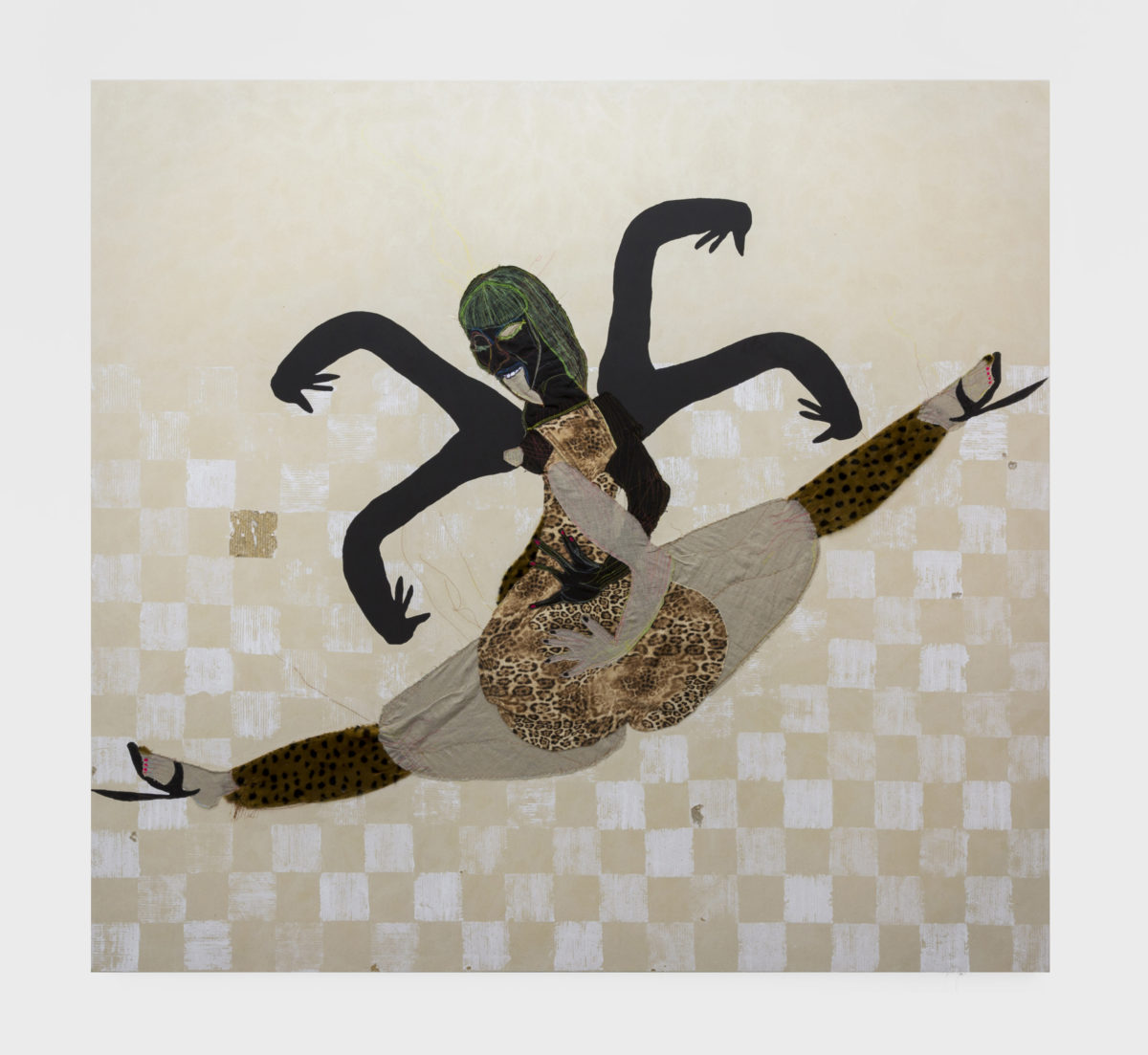

The nucleus of the Parasol unit contemporary art programme is principally to present mid-career surveys (those, for example, of David Claerbout and Darren Almond), but also to show emerging artists (Julian Charrière and Tschabalala Self) and, finally, to exhibit and hopefully allow a fresh evaluation of the contribution made by long-established artists, whose works have been somewhat less in the spotlight in recent years (Siah Armajani and Robert Therrien). Can you imagine, the Jannis Kounellis exhibition we put on in 2012 was his first-ever solo show in a London institution?

SC: What was your journey into this field?

ZA: It has certainly been a long and passionate one. I was surely born a curator, but first I achieved a PhD in Quantum Mechanics. That was one of the greatest things I did, because it opened my eyes to so much else and kept me humble, something we terribly miss in this twenty-first century world of ‘stars’. I started in the Art world by assisting a curator at the Whitney Museum of American Art, while simultaneously earning my undergraduate credit and an MA from Columbia University in New York, followed by a year at the Curatorial programme of the Whitney Museum Independent Study Programme (ISP). I was also fortunate enough to guest-curate an exhibition for one of the Whitney Museum branches, before becoming the first director of the Swiss Institute in New York.

SC: What does London, and particularly the Wharf Road address, offer you as the location of your organisation?

ZA: The gallery has an N1 postcode but is actually on the fringe of Shoreditch. Also, the side of Wharf Road where Parasol unit is located is in Hackney, but the other side of the road is in Islington. We serve both local communities as well as the international community.

When I set up Parasol unit in 2004, Tate Modern had recently opened, so it was a very exciting and optimistic time. It was the birth of London as a centre for contemporary art and there was so much to be done, especially as much of the international art of the post-war period had not been shown in London.

I had lived for many years in New York, and the post-industrial location of Wharf Road in the East End of London reminded me of 1970s Soho in New York, so choosing the location was totally natural. Also, at the time, there were no other cultural institutions nearby and it was an area I could afford to buy into.

SC: How has the building’s features affected your use of the space?

ZA: The building was formerly a Victorian furniture factory, full of columns and very dark, but it had a wonderful human energy about it. The Italian architect, Claudio Silvestrin did a great job of designing the new gallery and integrating most of those columns. His conversion created an elegantly straightforward space that is loved by all the artists I have so far invited to show at Parasol unit. For me, aside from the clean and minimalist gallery space, the building itself seems to retain the soul of people, those who worked here over so many years, and I believe the space reflects that.

SC: What are you currently working on?

ZA: As the only curator at the foundation I am usually planning 18 months ahead and working on at least six projects, each one at a different stage of development. Along with everything else, we are currently working on a solo exhibition by the renowned American artist Martin Puryear, for September 2017. Despite having had a MoMA retrospective, Puryear has not yet had an exhibition in London. We are thrilled, too, about the other projects we are working on. Also, I write quite a lot and contribute at least an essay to each publication. I love this activity, because writing about an artist’s work helps me to more fully enter into and understand the artist’s way of thinking and working. This is always a very important moment.

SC: How do you go about discovering and selecting artists to exhibit? Are there any platforms you look at to find emerging talent?

ZA: Like most curators, I am always travelling, looking and seeing. So there is never any particular set of rules or platforms to follow. Obviously, with the more established artists I have shown, I was already well acquainted with their work. For others, I have had to rely on my own judgement and gut feeling. It is very fortunate for me to have been given the right instinct.

SC: What are the biggest challenges facing London art institutions today?

ZA: London has experienced a golden age, at least in contemporary art terms, in the 17 years since the opening of Tate Modern in 2000. This shows how grateful we should all be for the fantastic spirit and work that Sir Nicholas Serota has contributed. I certainly hope this well-being will continue, beyond even Brexit. The leaders of London’s art institutions have been very open and innovative, which has encouraged a significant number of well-to-do and sophisticated foreigners who live here to think of London not only as a world city but also as their own home city, and to contribute to it with extreme generosity.

I just hope we all realise what it means to achieve success so rapidly. The example of other cities shows that success is not eternal, but I believe London has used its success very intelligently. Success comes with its own pressures, but we all have to take care and remain focused in our roles as museum directors and curators of public art spaces. After all, we have the huge responsibility of being makers and should be ever vigilant about not giving in too much to superficiality.

SC: Parasol unit offers a diverse educational programme of events alongside its exhibitions. Could you tell us about the thinking behind this?

ZA: Thanks for appreciating the importance of our educational programme. Of course, as a small institution with limited financial means we have to be constantly alert to what is right for us to do, and to change direction if something is not working well. The education programme is planned very much around the exhibition programme and content, which is largely international. Our children and family programme is set up to support the community and every year we try something new, such as the storytelling workshops, awakening an interest in art at an early age and, latterly, in December we hosted the first, two-day, presentation of The London Children’s Book Fair.

SC: Are there any artists, in London or elsewhere, who you think are currently doing especially interesting work?

ZA: The Julian Charriere exhibition we held in January 2016 is one example of the incredibly interesting work that young artists are doing these days. The millennial generation is responding intelligently to the challenges of their time – whether it is the pollution, depletion of resources (Lithium in the case of some of Charriere’s work), and still the issues of gender and race (for example, Tschabalala Self currently showing at Parasol unit). We need only keep close contact with them to find dozens of other examples.

SC: How is Parasol unit distinct from other art spaces in the city?

ZA: That is really for the audience to define. We just do our work the way we think will best serve the public and are hugely grateful for the support we receive from people like you.

SC: Could you tell us about some of your achievements of which you are most proud?

ZA: To respond right away, I am never proud about what I do, because the day I indulge in feeling pride, I will lose my motivation and spontaneity. I was raised in a very old Persian family with a wonderful sense of civil service, where the motto was: with privilege comes responsibility. I will be proud if I can stay that Persian girl, who never becomes established and remains curious about developments in our world.

SC: Could you tell us about your experience of curating your first show at the Whitney Museum of American Art?

ZA: It was truly rewarding, and what a privilege for a non-American to curate a show for the Whitney Museum of American Art. During my studies for the Masters degree at Columbia University, I had the pleasure of, among other subjects, studying with the great scholar of American Art, Barbara Novak. She opened my eyes to the difference of vision between American and European artists, and their understanding and philosophy of the physical world, which by the way exists still.

One of the American artists, whose work we studied in depth was Winslow Homer (1836–1910). I realised how his seascapes, in particular, developed over time from genre and amusing works to some stern and monumental paintings that bordered on abstraction. It therefore seemed a good idea to suggest such an exhibition to the museum. Luckily they accepted my proposal and we held the well appreciated exhibition ‘Winslow Homer and the New England Coast’ at the Whitney Museum branch in Stamford, Connecticut, on the coast of New England.

Homer is not a household name outside the USA, but is definitely so throughout America, where his works are not only considered extremely precious, but are often owned by some of the country’s smaller institutions. My job was not simply to send loan request letters and include a form, but rather to visit the director of each of the institutions and convince them of the importance of the proposed exhibition. It was quite a challenge, and when my efforts did not always bring about the required result, Thomas Armstrong III, the then director of the Whitney, helped out greatly and generously. This showed me early on that if one sets one’s mind to something, it is possible to achieve it.

SC: What do you find is unique about London’s art community?

ZA: Its enthusiasm and openness to what is happening around the world.

SC: What piece of advice would you offer to an aspiring curator?

ZA: If I may, I would advise them to avoid stardom. Far more important and interesting is to work very closely with the artists. Look and listen. Also, write a lot. Writing is a kind of communion with the artist.

SC: Are there any art spaces in London that you feel are doing something particularly exciting right now?

ZA: Frankly, we are all doing our best and I am often in awe of how some institutions in far distant places remain so upbeat, enthusiastic and creative. Let’s hope this will continue.

SC: Do you have a favourite place to shop in London?

ZA: I hardly have time to shop, but I live near Marylebone High Street and I love that neighbourhood.

SC: A favourite restaurant in London?

ZA: May I introduce you to Sardine, the newly opened restaurant at Parasol unit. Under the direction of chef, Alex Jackson, it has blossomed. Otherwise, I love the calm and space in Locanda Locatelli in Portman Square. I often go there for business meetings – you can really talk there without having to shout!

SC: Favourite travel destination or where would you live if not London?

ZA: Engadine Valley, Switzerland.

Tschabalala Self at Parasol unit till 12 March 2017

Interview by Keshav Anand | Photography by Sanne Glasbergen