A Guide To Relational Aesthetics

By Something Curated“Relational aesthetics” is a term coined by art critic, historian and curator Nicolas Bourriaud, originally for the exhibition “Traffic,” held at the CAPC musée d’art contemporain de Bordeaux in 1996. Inseparable from the concept, Bourriaud further expanded on the term in his 1998 book, Relational Aesthetics, defining the movement as: “A set of artistic practices which take as their theoretical and practical point of departure the whole of human relations and their social context, rather than an independent and private space.”

Formally born in the 90s, following the birth of the Internet and the concept of virtual networking, Relational art saw artists endeavouring to communicate with viewers through participatory installations and events. Relational artists rejected the making of conventional art objects, opting to engage audiences through situations which called for, and at times demanded, interpersonal interaction, facilitating community among participants. These practices have their roots in earlier art movements, namely Dada, Conceptual art, Fluxus, and Allan Kaprow’s “Happenings.”

In 1992, art dealer Gavin Brown helped artist Rirkrit Tiravanija transform 303 Gallery, then on Greene Street, into an operational kitchen for a part performance, part installation piece titled “Untitled (Free).” Tiravanija, in perhaps the most cited work of Relational art, moved all the contents of an art gallery storeroom and office into the exhibition space and staged his work in the back rooms; the art consisted of cooking Thai cuisine for his audience. The viewers became active participants, first locating the backrooms, then consuming the food and engaging in conversations with the artist and one another.

Big Conference Centre Limitation Screen, by Liam Gillick, explores architecture’s role in human interactions. Part Minimalist sculpture, part corporate capitalist architecture, his structure is seen ultimately as a mere “backdrop or décor” for the interactivity of audiences. “Despite their affinity with minimalist architectural design, Gillick’s installations are characterised by their indeterminate look, halfway between decorative and utilitarian, fact and fiction. Deliberately deceptive, they require viewers to rethink their own ways of perceiving and interpreting art,” art critic Charlotte Laubard writes.

The community project, Streamside Day, by French artist Pierre Huyghe, consisted in part of a parade and celebration in a suburban development. In an interview with Art21, the artist explained: “Streamside is a little town, north of New York. It was under construction when I found it, and I created—or invented—a tradition for it. I was interested in the notion of celebration, and what it means to celebrate. I tried to find a story within the context of the local situation, looking for what the people there had in common.” Members of the Streamside community can choose to execute the celebration again each year, not unlike playing a composer’s score.

Vanessa Beecroft’s work is largely performance-based, often featuring female models as living art objects that exist somewhere between figure and object, static and dynamic. Much of Beecroft’s work is informed by her personal struggle with an eating disorder and she consistently explores issues of body image and femininity in contemporary culture. For VB35 at New York’s Guggenheim Museum, Beecroft instructed her live models to stand motionless, clad in designer shoes and rhinestone bikinis, or in some cases simply in shoes. Guests of the exhibition had an uncanny encounter with figures that resembled fashion advertising images but were in fact live human beings.

Relying exclusively on the human voice, bodily movement, and social interaction, Tino Sehgal’s works uniquely fulfil the parameters of a traditional artwork with the exception of inanimate materiality. His situations produce meaning and value through a transformation of actions rather than solid materials, as was particularly evident during Sehgal’s 2010 presentation of This Progress at the Guggenheim , when he stripped the Frank Lloyd Wright–designed rotunda of all physical artworks, and employed the ramp as a platform for discourse. Sehgal trained special docents of all ages to guide visitors up the museum’s ramp, having conversations and discussions with them as they walked.

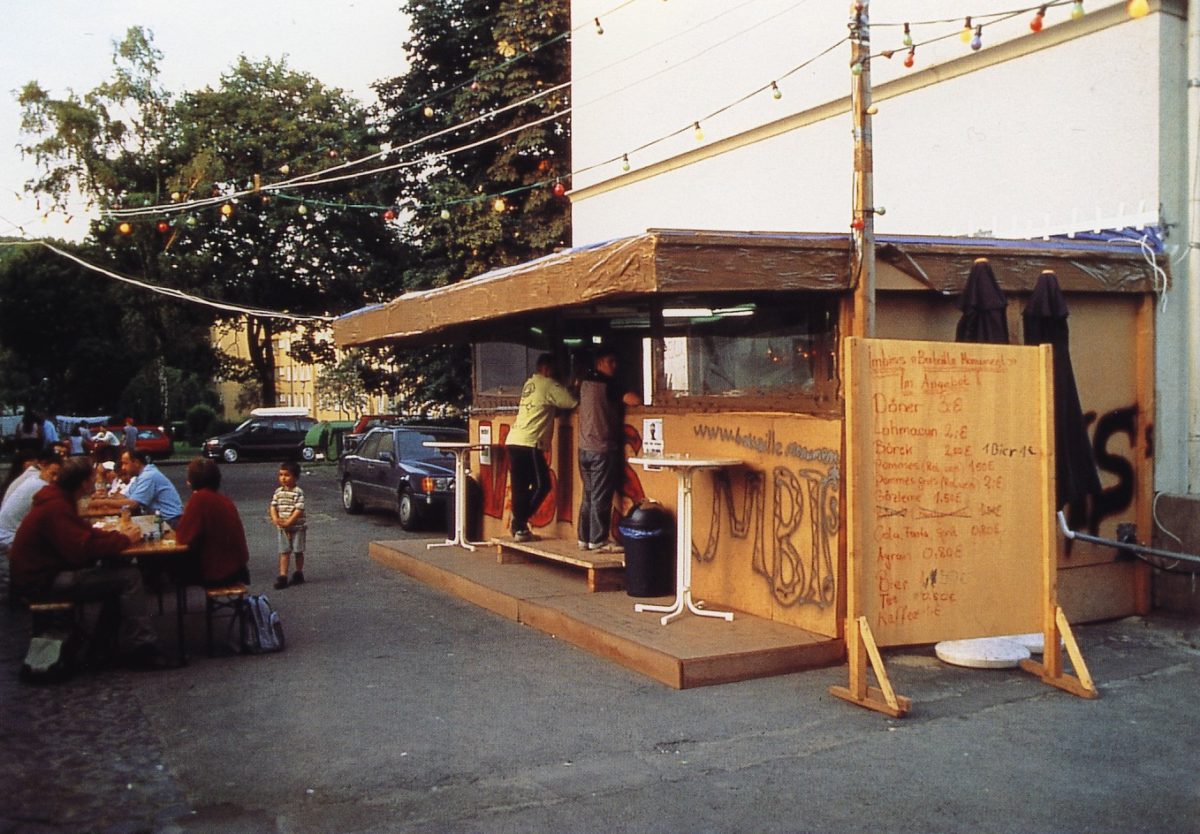

Art scholar Claire Bishop has been a critical voice regarding certain aspects of the movement, arguing that artists such as Tiravanija and Gillick do not democratise art but simply reinforce their pre-existing, closed art world and thus ignore its implicit class politics. For Bishop, Relational artist Thomas Hirschhorn offers an alternative by highlighting underlying social antagonisms. For Documenta 11, held in Kassel, Hirschhorn worked with locals in a nearby low-income, immigrant neighbourhood to erect a temporary structure that served as a site for community debates on the writings of French philosopher Georges Bataille. Participants from the neighbourhood could, and did, voice their opinions on Bataille in the monument’s makeshift television studio, thus becoming part of the art while viewing it.

More recently, between 2008 and 2009, The Double Club, a project conceived by artist Carsten Höller and Fondazione Prada, saw a converted Victorian warehouse beside London’s Angel tube station offer a unique approach to entertainment and hospitality, creating a dialogue between Congolese and Western contemporary music, lifestyle, art and design. Open for a limited duration, The Double Club was not only a vibrant new public space in the city but also an alliance of two cultures in real life, facilitating cross-pollination without any attempt of fusion. The Double Club consisted of three spaces: Bar, Restaurant and Disco. Each space was divided into equally sized Western and Congolese parts on a decorative and functional level, generating an inspiring perspective on double identity as well as on cultural coexistence.

Feature image: Rirkrit Tiravanija, “Untitled”, 1996, Le Consortium (via Le Consortium)