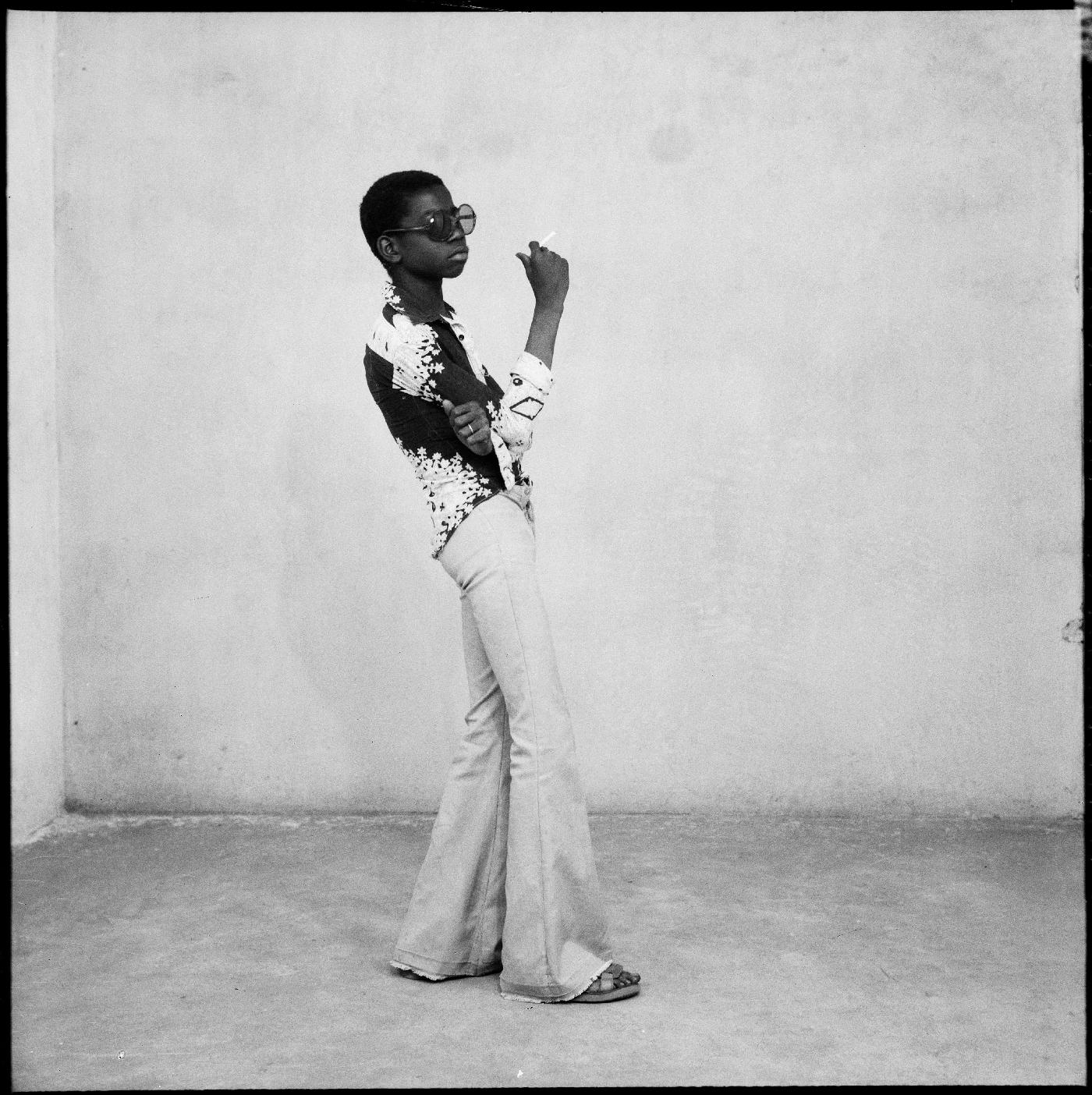

The African Photographer Who Chronicled The Exuberant Life Of Mali’s Youth

By Something CuratedBorn in 1936 and hailing from Soloba, a small town in southwestern Mali, Malick Sidibé’s flair for drawing was recognised by the French colonial administration during his youth. As a result, at sixteen, he joined the École des artisans Soudanais in Bamako, Mali’s capital. There, Sidibé had his first portrait taken by Malian photographer Baru Koné, who taught him about composition and light. Sidibé graduated with a degree in jewellery-making in 1955 and was employed by Frenchman Gérard Guillat-Guignard to paint the interior of his studio and photo supply store, Photo Service, where he later served as photography assistant.

Watching Guillat-Guignard in the darkroom, Sidibé taught himself to develop and print negatives. In 1956, he took on the responsibility of all of Photo Service’s party photography, shooting events for a breadth of West African clientele. Shortly thereafter, Sidibé received reportage commissions directly, and by 1957 had become a professional photographer in his own right. That same year, he started repairing cameras, a trade for which he became well known throughout Mali and its neighbouring countries.

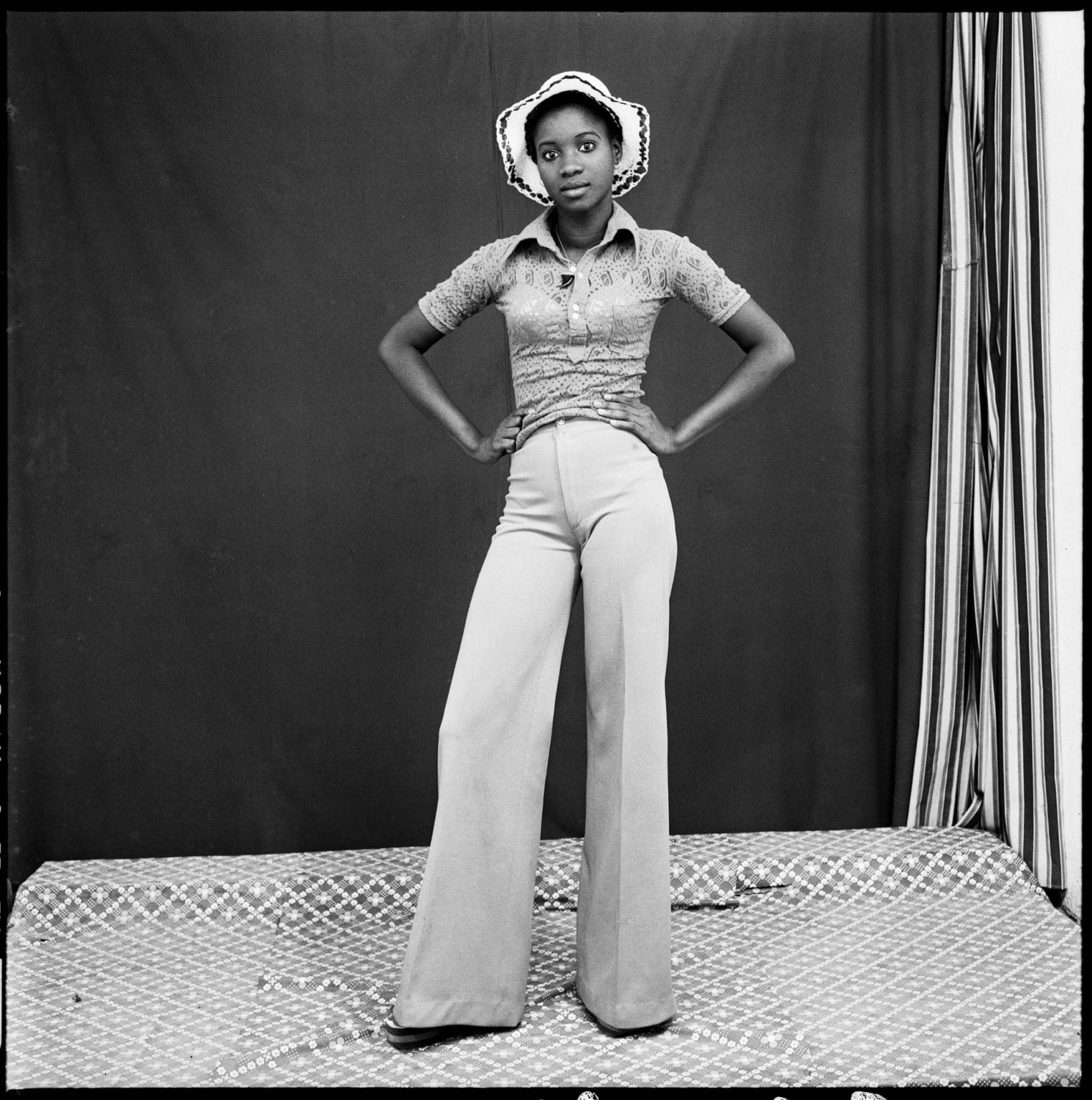

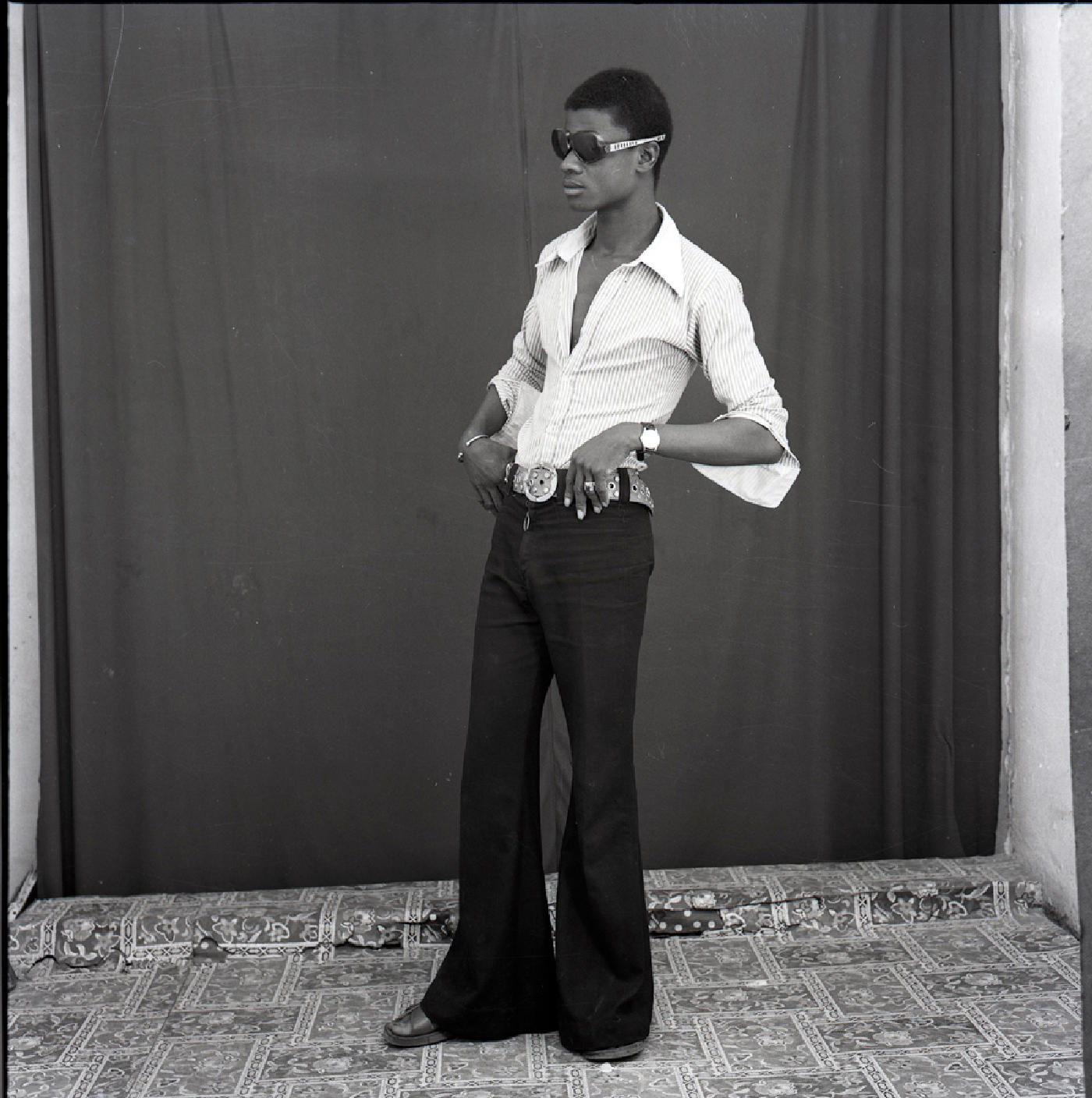

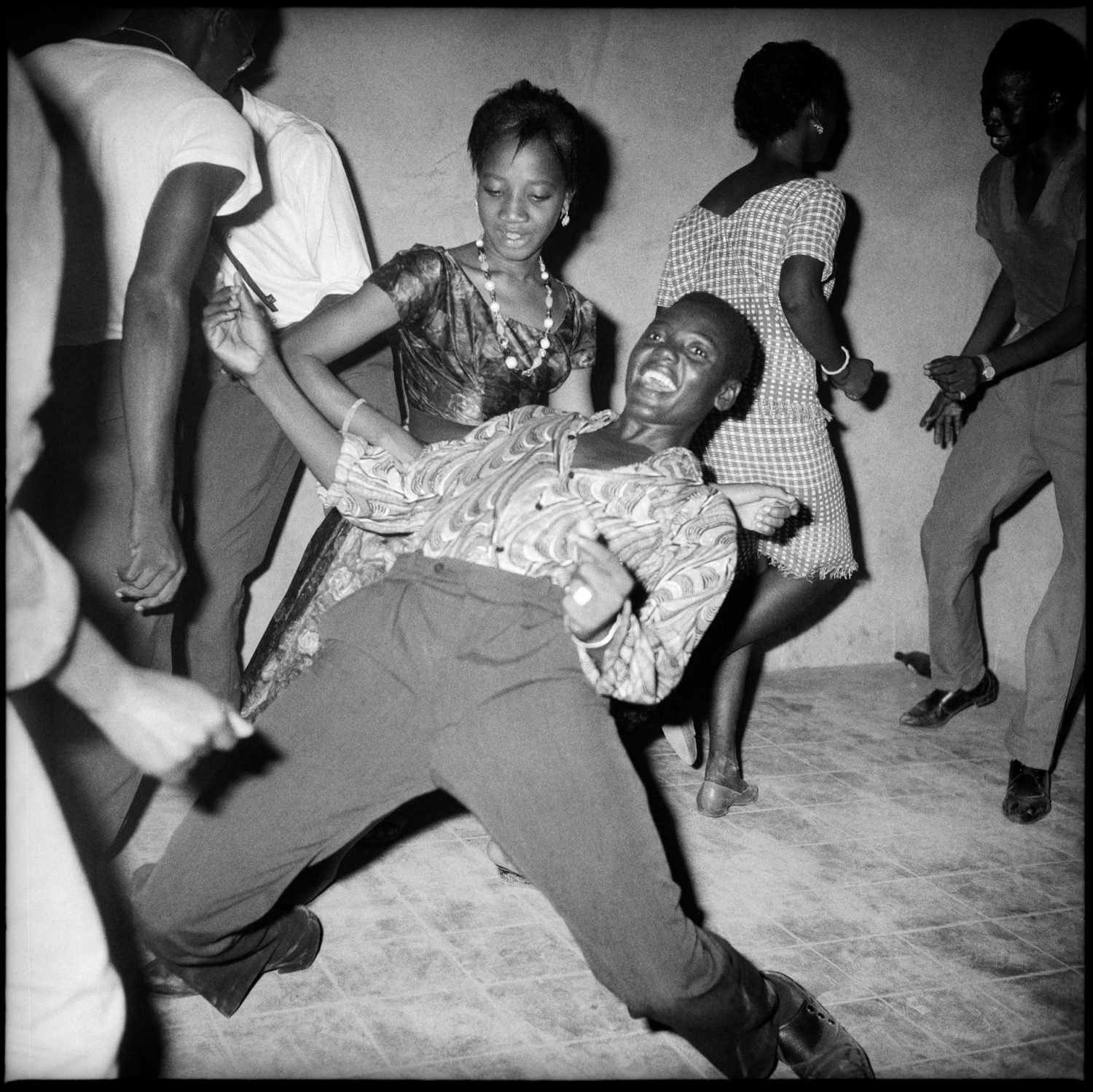

In 1962, Sidibé launched Studio Malick in the district of Bagadadji, which thrived during its heyday in the 1960s and 70s. His commissions included studio portraits, photos of weddings, baptisms, surprise parties, and picnics, as well as pictures of railroad, highway, and architectural construction. He captured candid images in the streets, nightclubs, and sporting events, as well as shooting in people’s workplaces and homes alongside his formal portrait studio. Sidibé’s work captures a transitory moment as Mali gained its independence and transformed from a French colony imbued with old traditions to a modernised and independent nation.

In a 2010 interview with John Henley in The Guardian, Sidibé explained, “To be a good photographer you need to have a talent to observe, and to know what you want. You have to choose the shapes and the movements that please you, that look beautiful. Equally, you need to be friendly, sympathique. It’s very important to be able to put people at their ease. It’s a world, someone’s face. When I capture it, I see the future of the world. I believe with my heart and soul in the power of the image, but you also have to be sociable. I’m lucky. It’s in my nature.”

From 1998 to 2009, Sidibé regularly photographed for titles such as Vogue, Elle, Cosmopolitan, and the New York Times Magazine. His jubilant and spirited style of documentation, which blends urban symbolism with bold patterns and theatrical compositions, has also inspired numerous fashion designers, photographers and filmmakers around the world, as evident in Gucci’s “Soul Spirit” campaign of 2017, among other homages. In the twenty-first century, Sidibé continued to experiment with photography projects and developed inventive ideas for exhibitions, until his passing in 2016.

Feature image: Malick Sidibé, Un Jeune Gentleman, 1978 | Images via Pinterest