Interview: Toyin Ojih Odutola On Her New Exhibition At Barbican Art Gallery

By Keshav AnandFrom 11 August 2020, Barbican Art Gallery hosts A Countervailing Theory, the first-ever UK commission by Nigerian-American artist Toyin Ojih Odutola. An epic cycle of new work unfurls across the 90-metre long gallery, The Curve, documenting an imagined civilisation conceived by the artist. Drawing on an eclectic range of sources, from ancient history to popular culture, Ojih Odutola investigates the power dynamics at play within this community. Working exclusively with drawing materials, Ojih Odutola’s works often take the form of monumental portraits, which retain a remarkable intimacy despite their scale. Her work is concerned with drawing as a process of storytelling, and she weaves speculative tales, which question familiar histories and pose alternative realities. To learn more about the artist’s work, her upcoming Barbican show, and how she has handled the pandemic, Something Curated spoke with Ojih Odutola.

Something Curated: Can you give us some insight into your background; how did you enter this field?

Toyin Ojih Odutola: I remember saying in an interview with Elephant Magazine: “I go blindly forward with an inquiry—not at all concerned with the answer or the outcome, but with the lands, states and spaces I travel through in the process of making.” That’s the closest to describing how I got into drawing. It was a meditative, focused activity for me as a child. A means of arriving at an understanding. Having travelled extensively with my family before settling into the American South, I was mired with the fear of disappearing, not able to claim the ground I stood on.

Art-making became “home-making” for me. And the deeper I delved into it—the more probing the questions I investigated—the more my home expanded and gave me agency. I can’t in all honesty say I always wanted to do this, or it was somehow predetermined, because for so much of my life I felt my presence was an accident. A nagging voice in my head telling me, “you aren’t meant to be here.” The gift my drawings have given me is the pride in my existence, in my place in this world, and the power to choose how I express that existence and communicate the imaginary within me to strangers. For a long time I was consumed with how I might be regarded by others, and it permeated my work. That no longer is my concern.

SC: Tell us about your upcoming site-specific installation for The Curve, A Countervailing Theory.

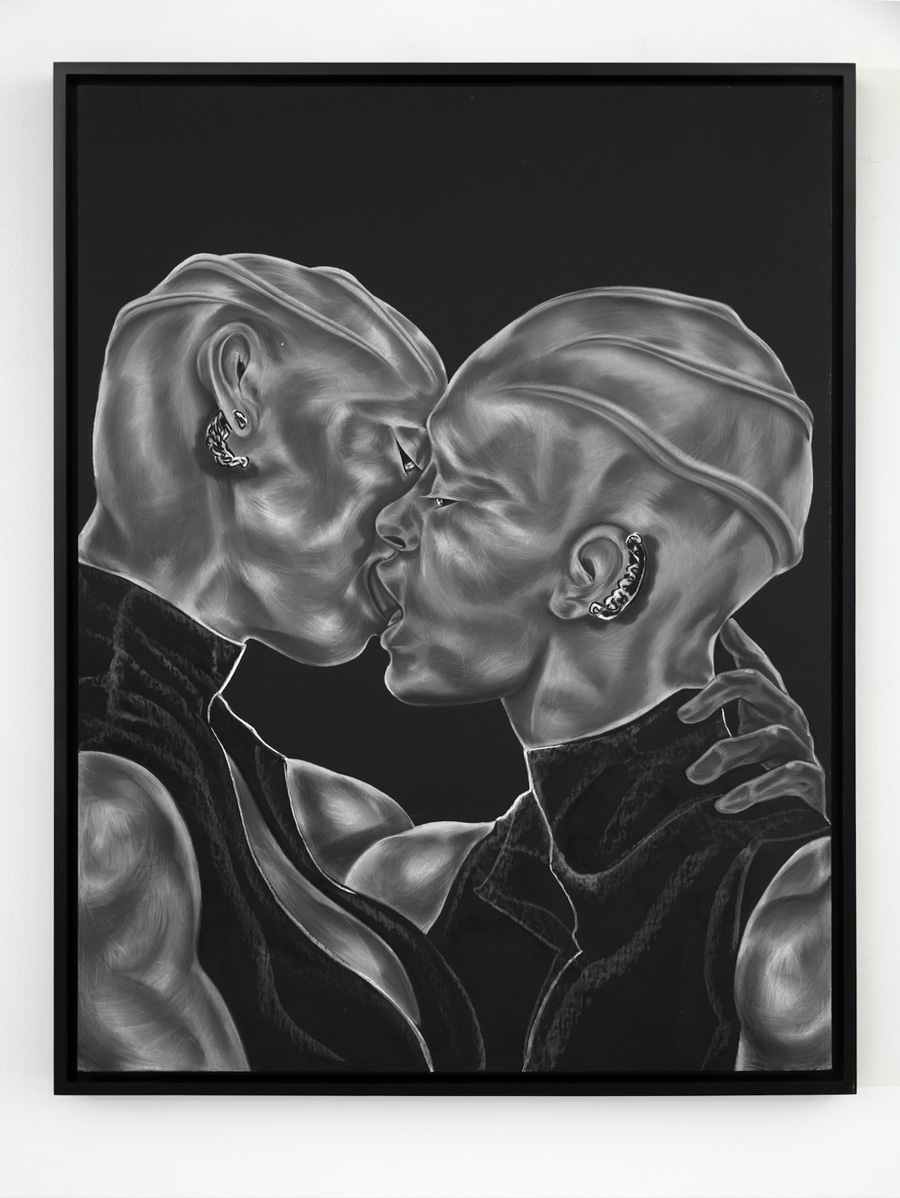

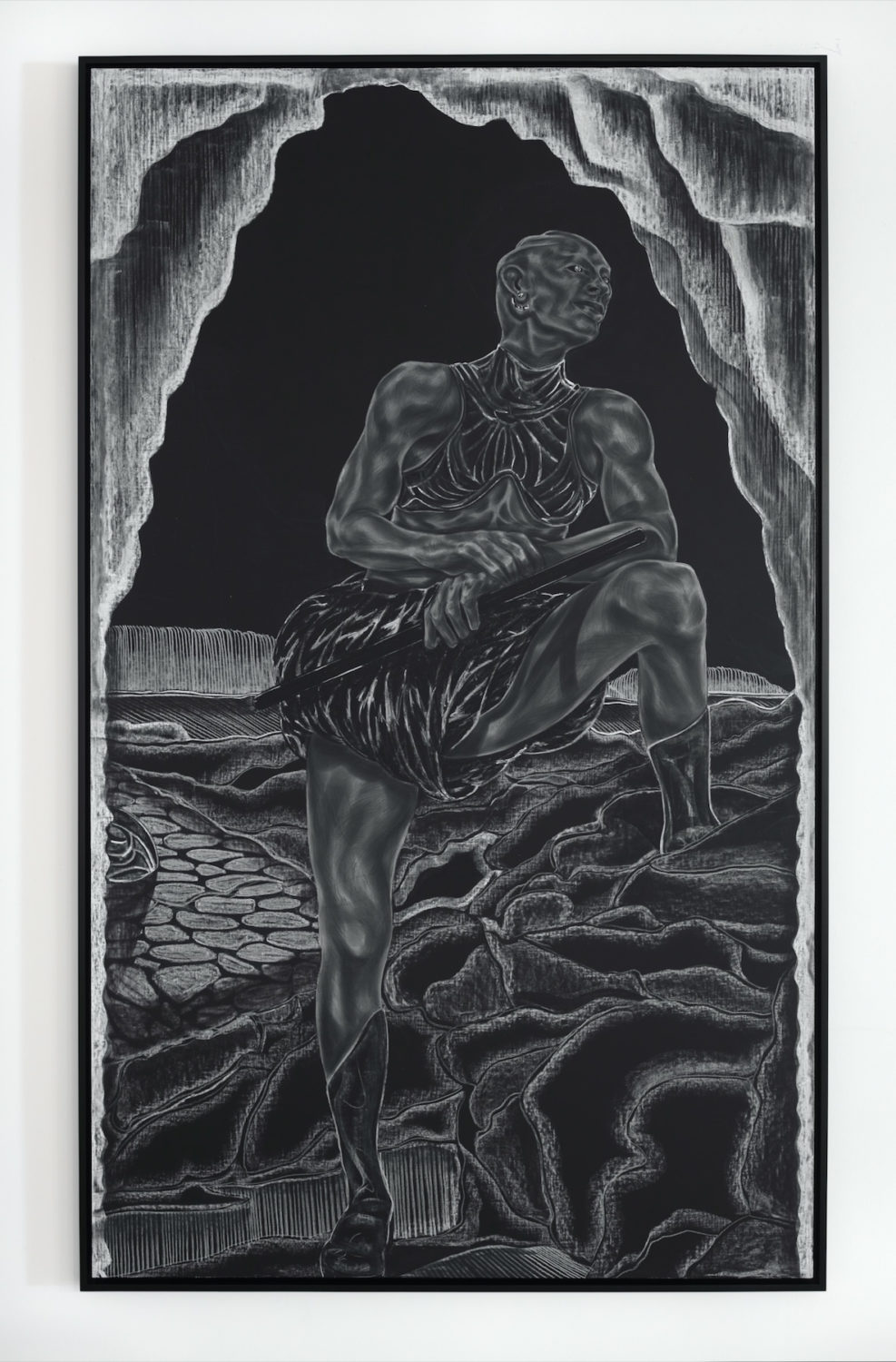

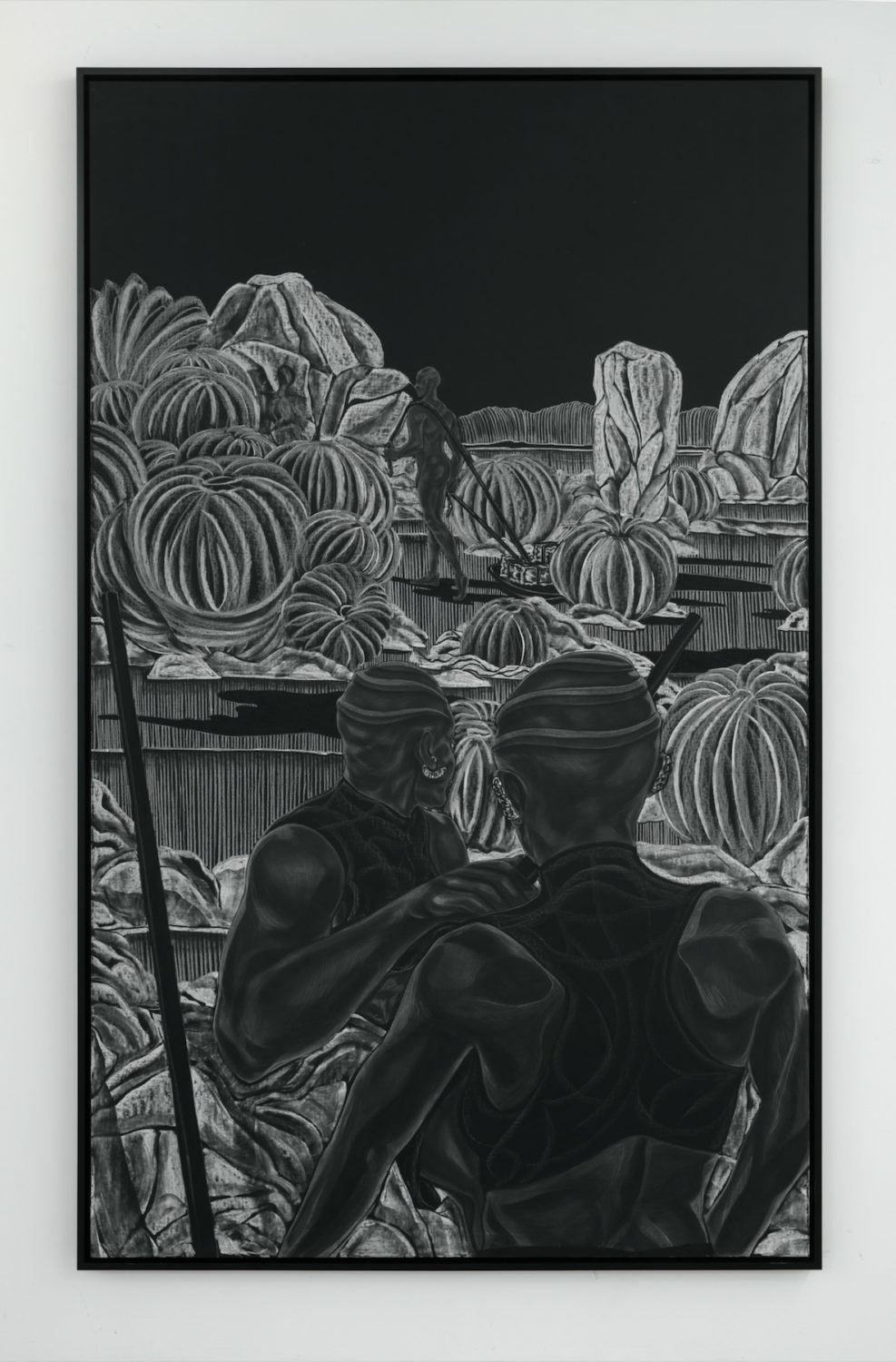

TOO: A Countervailing Theory is an attempt at conjuring a parable that plays into multiple layers of meaning. It’s about engaging in the act of myth-making—the original “History”—and the questions partaking in that activity brings up as well as the answers that I may not be conformable with confronting. It posits an ancient civilization set in central Nigeria (Plateau State), and the famous rock formations found there, with notions of power, how societies and systems are formed, who benefits from the stories we tell ourselves, and how lovemaking is an act of perturbation. To mine a history containing millions of years of natural as well as human-made development and using myth-making as the means of engagement was an exciting project to delve into.

I also wanted to engage with a land I’d never visited, Jos Plateau, and letting my imagination carry me into a place that felt familiar although I knew very little of it going into this series. The Curve is a great metaphor as a space, for you can only move through it in one direction. To proceed is a choice, and every turn is akin to rolling out a hand scroll in increments. You don’t know what is coming, and you can’t go back to where you started—you have to trust whatever is coming will provide some more answers as you piece together the puzzle. Wherever you arrive at the end becomes unimportant, the process, the formulating of meaning, as you go through it takes precedence. That was my experience building this world. I hope whoever comes to visit senses that parallel, that connection, as well.

SC: Could you expand on the fictional prehistoric civilisation your work conceives? The surreal landscape your saga occurs in is loosely based on the Plateau State in central Nigeria – what draws you to this particular topography?

TOO: The idea of the story came to me from two points: one, was noticing my proclivity towards drawing landscapes in a particular way while tackling the gessoed-linen as a surface—something I’d never done before as I’ve mainly worked on paper; and two, trying to find a real world, visual equivalent to explain this. Reading about the rock formations of central Nigeria in a geological science journal was an epiphany. The marks I was making felt ancient, or rather, they came from a place within me I wasn’t acquainted with, but was somehow subliminal and intimate. Finding a location which connected to those marks, that existed in the country of my origin though I’d never been, felt like a sign, a creative license, to delve deeper into the “why.” Material often dictates my work and the stories proliferate from that.

Working with a monochromatic palette in pastel, charcoal and chalk, I was creating a visual language that was direct yet seemingly unknown to me. I felt it was mine in the sense that it harkened from my ancestors. I can’t think of any other way to describe it. I was mining a history within me, as I was sourcing all the research required to learn about the Plateau State region. The land I thought was lost or the land I felt was lacking, was full of so much depth and richness. It was difficult to work through: I had to remove preconceived notions and the implicit biases I had; there were moments I struggled to formulate the language to build this story. To translate what I was discovering, I made mistakes and fumbled often, yet I am proud of the work in this series. I gave it my entire self. I didn’t hold back anything. These two modes—that of central Nigeria and the metaphysical world—worked in tandem to formulate A.C.T. What you see on The Curve gallery walls is a document of that mining—the land that was found.

SC: How has the pandemic affected your way of working?

TOO: The word “overwhelmed” has persisted the entire time we’ve been in quarantine—since March of this year. I sensed, at least in New York, a collective exhaustion we’d hoped to be freed from in 2019 come in 2020. What has transpired these five months alone no one was prepared for—every aspect of our societies are affected. The virus has exposed the inequities and deeply rooted problems of which we are all complicit. There is no corner for us to run to for solace—all is connected to this mess. It makes getting up and trying to work feel fruitless and uninspiring. It makes you question everything. You search for a means of controlling your little plot of this frantic, cacophonous world. I’ve been blessed to have drawing, to have a roof over my head, to have access to food and to drink filtered water…that I can still breathe. The pandemic has made me more appreciative of my life, and that is no small thing. The work I choose to do moving forward has been deeply affected by that. I’m no longer concerned with managing how my work is to be interpreted, how it might become subsumed by colonialist connotations and impositions. I must create what I can with the time I am allotted and it must come from a place within me that is true, even if it makes me uncomfortable, even if it’s difficult. Because I am devoted to a collective healing project, not an imperialist one.

SC: And what do you want to learn more about?

TOO: I’ve often focused on how best to understand the patterns, the machinations, which make up our society and how to apply that knowledge into my work—into a kind of visual language. The knowledge and perspective that gifts is instructive as it is equally infuriating. Lately, I find the anger incredibly intense and tiresome. In times like these, resilience is key, but I have to be mindful of anger. Anger can be distracting if not stressful on the mind and body. Sometimes, anger makes you feel like you are being productive, for it motivates you to try and enact change—to contribute to building a better world. Now, I’m slowly learning there are other ways, other emotions, one can gather and pull from to do so. It can be slower and more self-preserving. There is still so much I need to learn and unlearn, but I need to do it in a way that doesn’t make me feel like all is lost. I think that’s needed moving forward.

Toyin Ojih Odutola, A Countervailing Theory at The Curve, Barbican Art Gallery (11 Aug 2020 — 24 Jan 2021)

Interview by Keshav Anand / Feature image: Toyin Ojih Odutola, Mating Ritual from A Countervailing Theory (2019) © Toyin Ojih Odutola. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York