Interview: Simeon Barclay On Bonding Experiences, Comics And Growing Up Black In Britain

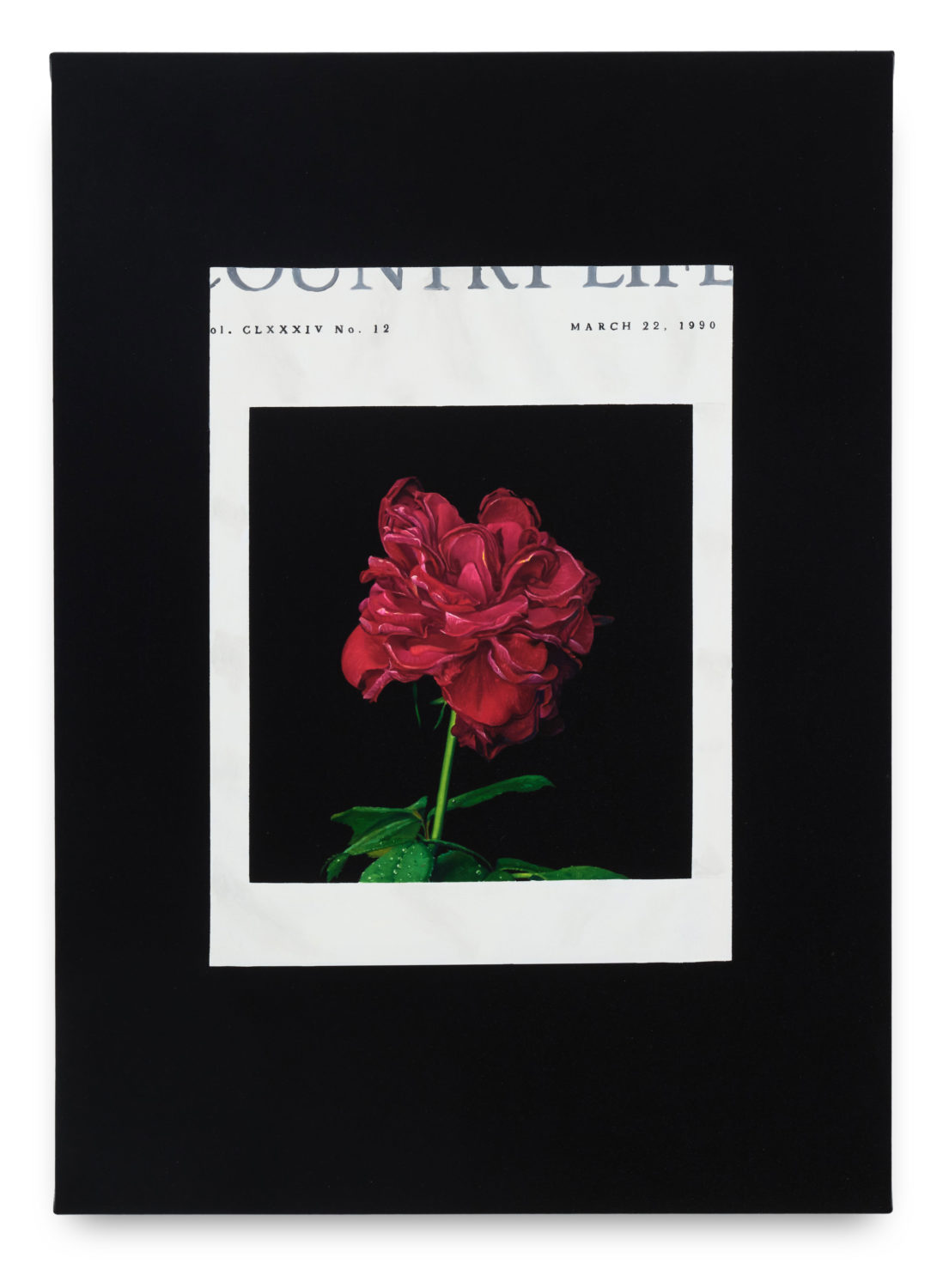

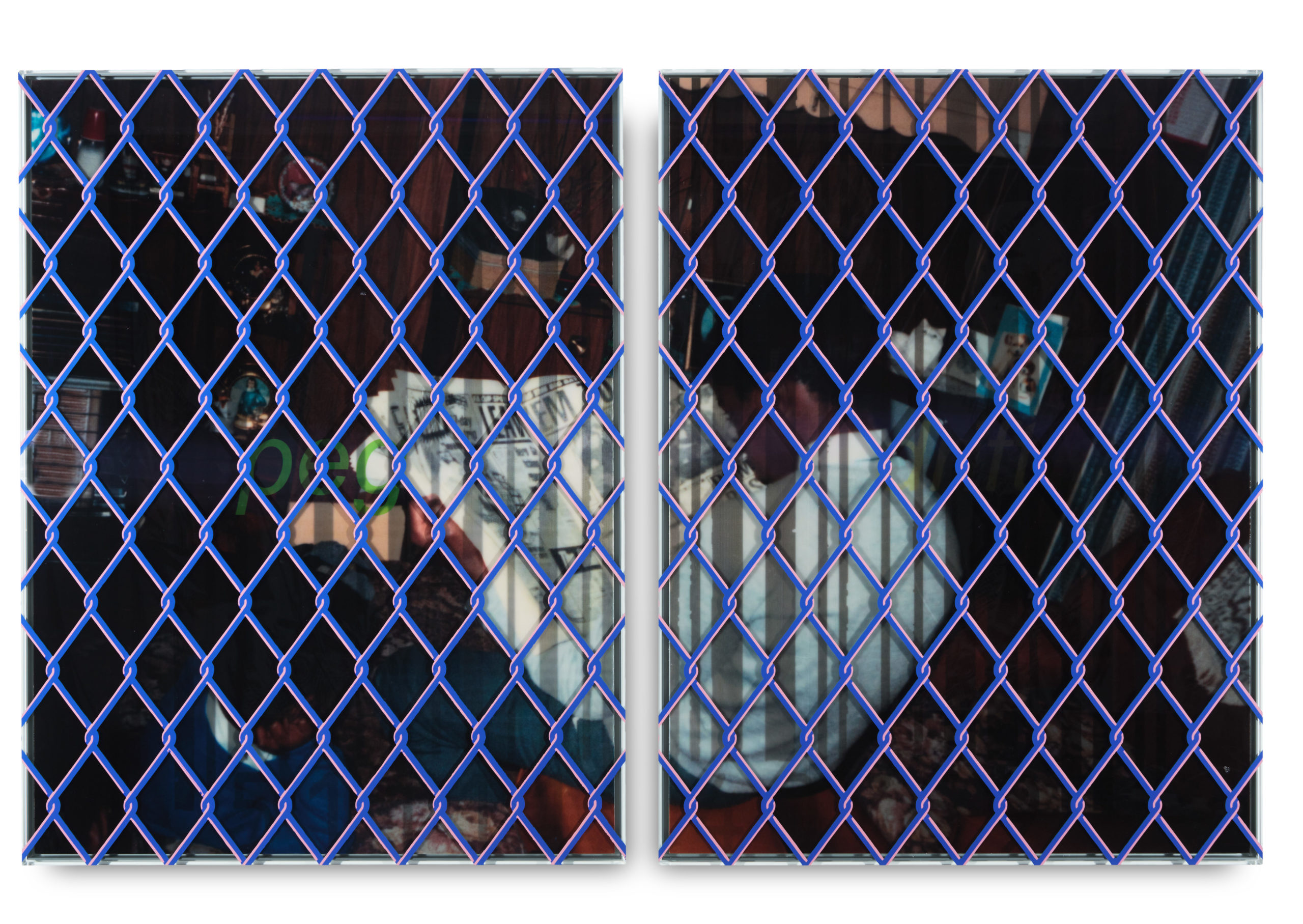

By Something CuratedOpening today, 10 September, and running until 29 October 2021, London gallery Workplace presents England’s Lost Camelot, an exhibition of new multi-media and installation works by British artist Simeon Barclay. The exhibition takes as its starting point the legacy of the gallant knight, examining the persistence of its associated iconography in British folklore and its lasting influence in the construction of still prevalent ideas of masculinity. Combining research of this medieval legend with reference to popular culture and his personal biography, Barclay continues to explore the contestation, and strategic negotiation of cultural narratives that influence our behaviour and conformity to archetypes. Dealing with the theme of exclusion, the works within the exhibition are populated by barcodes, fences, and other motifs that aim to obstruct the sight and complicate the viewer’s relationship to the images.

Expanding on his background and entry into art making, Barclay tells Something Curated: “Art making, for me as a young child, was a place of true expression. I suppose now people put me in a gallery and I’m able to takeover that space – I dominate it. But back in the day, the space I had was an A4 sheet that somebody would have given me. I would throw stuff onto it and push it about to make that page something that was cohesive for me. Making work has always been a place of refuge, of solace, in which I can escape. Art was something I was good at and I wanted to keep doing it – I got a special satisfaction from that, and was appreciated for it. Even with all that confidence around it, growing up as a working class child, there wasn’t that value around it. Not in the same way that there was value for the profession of a mechanic. There was no sense of being able to make money out of it. So as much as it could be enjoyed by people, there wasn’t any idea of where could this go? It was sort of like a folly in a sense.

I grew ambivalent to school and how it could benefit me, and left without any qualifications. Although I couldn’t articulate it, there was a pervading sense that I wasn’t meant to excel here. I went into engineering after leaving school and did that for around sixteen years. In that time, as a way of expressing myself, I put myself into various subcultural goings on – I became very into music and fashion, and football. These were all bonding experiences for me, a way to belong. Because I felt I couldn’t belong in society. Filtering myself through these people, I became somebody in certain scenarios. Work allowed me to pay for my existence but that’s not to say the whole experience wasn’t beneficial – it all came to have benefit in the end but it took a long time for me to see that.”

Barclay continues: “Towards the latter end, I started to become estranged from work. I always found myself attracted to things and spaces that people felt I had no business being in. Perhaps because of my class, I had a bit of a chip on my shoulder. I was always inquisitive and resisted being pigeonholed. I went to night school – I was this person at work, and once the day finished, I turned myself into another character. I was very at unease with that quality of life. Through my own education, I saw my true value at work. I was reading a lot of Marx and it unravelled the ideas I had of my work, and my existence. My partner at the time, who I then married, brought a different ethic and value to my life. In a sense, I married up. At the time, I was very insecure about my own background and the people I was now coming into contact with had all been to university.

I felt I needed to find something I was good at. I needed to be educated so I could control my destiny. So after night school, I went to university. This was an opportunity for me to reinvent myself in order to exist within this middleclass milieu. This was clear in the type of work I was making – I thought I could just get by by creating and not really dealing with the issues that I was going through. As a Black working class male from Yorkshire, this was something that was unavoidable in conversation – and I made the decision to hit it head on and deal with it. I began to try and understand my position in the world as a body outside of myself, reflecting on the perception that had already been thrown onto me.”

The installation elements in England’s Lost Camelot, which surround the works in the exhibition, feature artefacts and images borrowed from both British folklore and Black political resistance, and function as a way of understanding the often complex and ambivalent nature of belonging and subjectivity. These elements are interspersed with a series of collages constructed from the artist’s own personal archive of ephemera. This theme of exclusion continues throughout the exhibition informing the placement of works and their relationship to each other. A photo collage diptych of a young Barclay reading a red top newspaper is covered in the latticed cage of a wire fence, in situ, and obstructing the work’s view are two replica Great Helms emblematic of the helmets worn by knights in battle.

They have been battered and then embellished in black powder coated paint and hung at the artist’s head height to suggest the confinement of perceptions and the psychological masks needed to navigate the constraints and trauma of exhibiting a unilateral ideal of masculinity. As a code for invulnerability, isolation and defensiveness, the armour and its associated imagery still has a potent appeal. The artist looks at how these are embedded in the national psyche informing contemporary debates on the legacy of imperialism and nationalism and its residue as a history he has bequeathed as his inheritance. Barclay tells SC: “While the experiences are universal, I feel like America has its thumb on the signs and significations of Blackness, and for a long time, we were sort of overwhelmed with that. To a point, we still are. It’s a larger company – it’s able to disseminate ideas in a more heavy-handed way. For a long time I thought these were the only significations available to us, but I was always aware that my context was British, specifically British Caribbean. There is a different inflection on my experience.

We have to look at colonialism and how the islands of the Caribbean were indoctrinated with this very powerful idea of Britishness. I think about Christianity, I think about the Church, and ideas of conformity, ideas of the way you hold yourself, this stiff upper lip. I think it was the British that brought these values to the Caribbean islands. And like cricket, which we adopted and became so good at, this reserve, this stiff upper lip, has become a sort of Olympic sport. Certainly for my parents – my dad specifically. I wanted to unpick that in this exhibition. To understand my inheritance, and my relation with the UK. There is a comic called The Beano, which I grew up with, and there was a cartoon within it, The Numskulls, in which a family lived within the body of this character who navigated the world. And they lived in the character’s head, and they controlled the brain, and I see myself in that position. Britain being the body that I inhabit. It’s a relationship of love, of hate, and, at times, of indifference.”

Feature image: Simeon Barclay, Hear Between the Silence, 2021. Detail. Photo by Tom Carter. Courtesy of the artist and Workplace, UK