Interview: Chioma Ebinama On Collage, Colour & Her New Exhibition At Maureen Paley

By Something CuratedNigerian-American artist Chioma Ebinama is interested in how animism, mythology, and precolonial philosophies present a space to articulate a vision of freedom outside of Western social and political paradigms. Her practice is centred around works on paper, though in her travels she has collaborated with local artists to make sculptures, textiles and wearable art. Raised in the US by Nigerian Christian immigrants, Ebinama is drawn to the aesthetic of formalised religion for its potential to celebrate inner life. As she seeks to create new mythologies for the African Diaspora, her work is influenced by a myriad of sources, from West African cosmology and folk art of the global South, to the visual language of Western religion and Eastern spiritual traditions. Her work also reflects on gender and queer identities through a figurative language that is informed by surrealism and Igbo culture among other sources. The collision of aesthetics and presentation techniques is indicative of Ebinama’s nomadic life, exemplified in recent years as she carried her practice from Mexico to South Korea, India, Malaysia and now Greece. Now open and running until 9 January 2022, Maureen Paley presents the first exhibition by Ebinama at the London gallery. To learn more, Something Curated spoke with the artist.

Something Curated: Can you give us some insight into your background and how you first became interested in art-making?

Chioma Ebinama: I’ve always been interested in art-making but my path to where I am now has been a meandering one. As a child, I taught myself to draw because I wanted to be a manga artist and animator. However, I also had the typical mindset of most children of Nigerian parents, which is to take on a practical, financially predictable career path. I thought I would become a lawyer, but later concluded that art-making would provide me the most freedom. So I went towards being an artist, but in “practical” ways at first working in textile design and later in illustration. I don’t think I’ve ever had a clear sense of where I was going, I was just figuring out ways to keep making and to keep my time to myself.

SC: What is the thinking behind the selection of works included in your upcoming exhibition at Maureen Paley?

CE: This body of work feels very different. In the past, my images have arrived from lots of reading and writing. I like to begin with some kind of story. But I had no story this time. I have spent a lot of the past year and the year of the lockdown alone in a new country trying to figure out how to root but also grieving everything I left behind. Even though it was a very fortunate time, I felt alone and surrounded by a language that feels very alien to me. Even the pronunciation of my name is unrecognisable in Greek. There is no chi sound in Greek. In Igbo, chi is one’s personal god or destiny. It’s an Igbo woman’s most direct connection to her ancestors, to her history. The sudden uncertainty of meaning, in translation to Greek, seems like the perfect metaphor for the trauma of change or migration. In a conversation about rooting, a friend asked me to consider what language do I hear myself in everyday? I feel this work is an attempt to hone into that voice.

SC: You work with a very particular palette — how do you think about using colour?

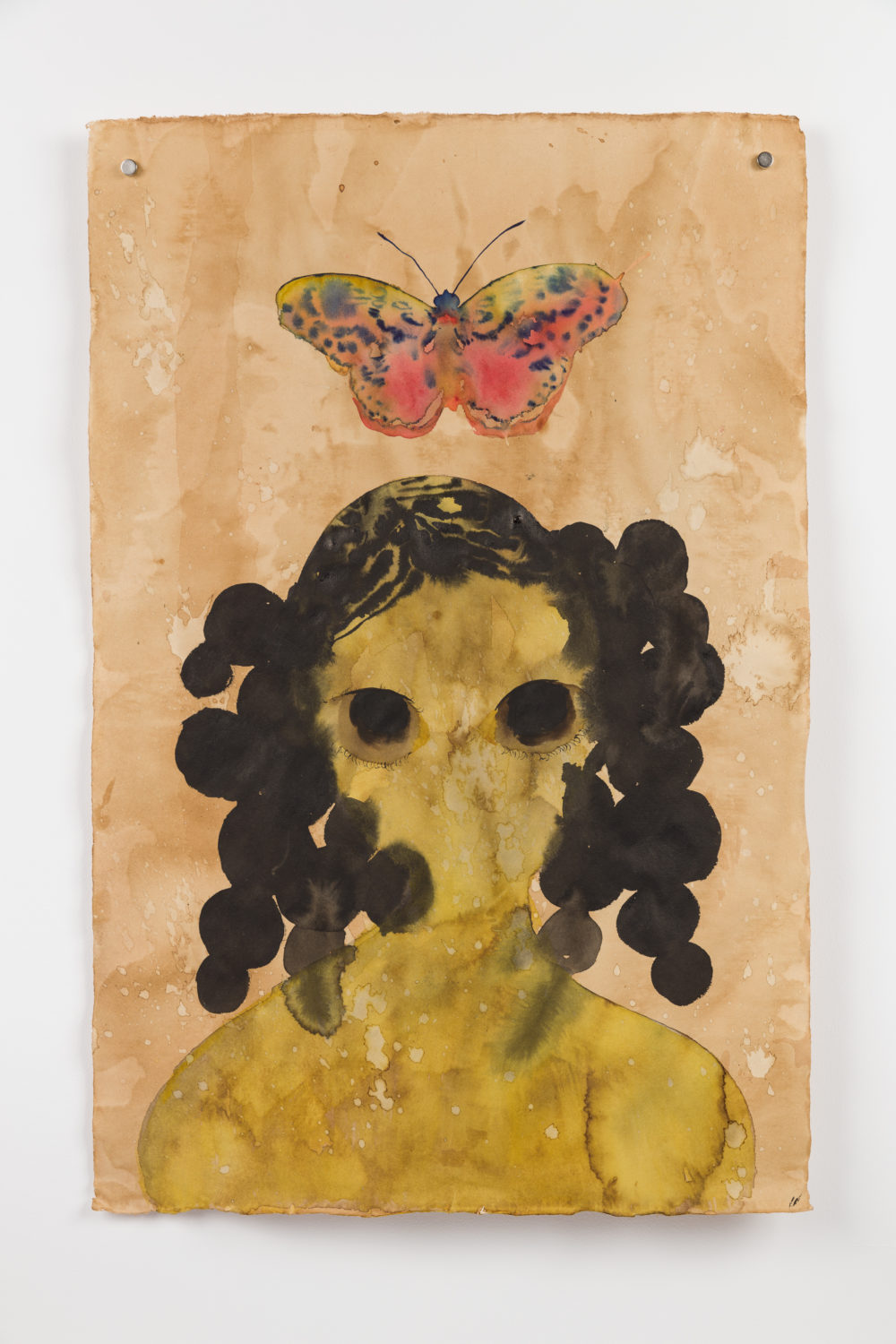

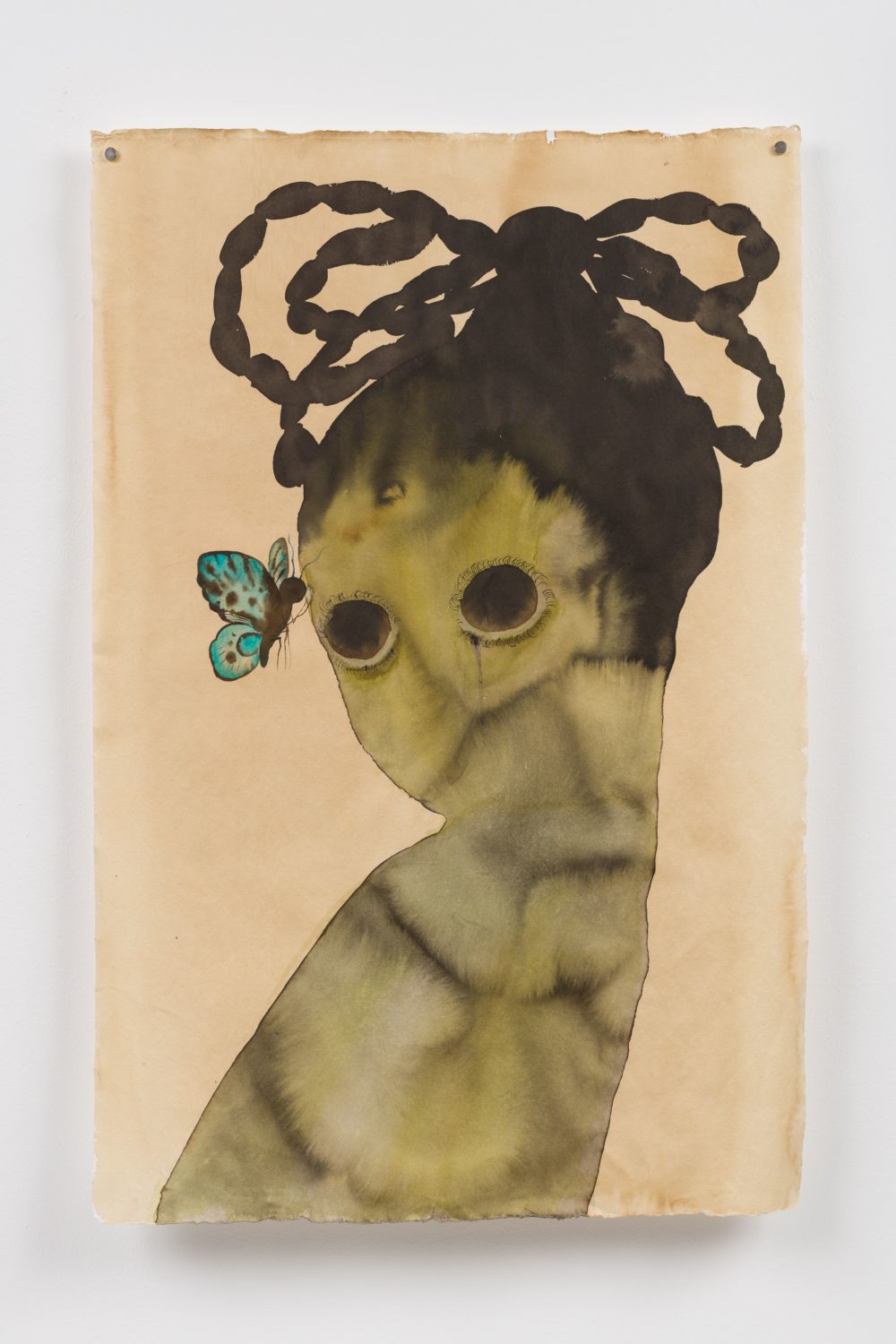

CE: I’m very sensitive to colour. For this show I really wanted to get away from a bright palette. Partly because I had spent a lot of this year illustrating a children’s book, Emile and the Field, which comes out in Spring 2022. It has a lot of colour and the colour plays a huge part in moving the narrative. As for this show and my other fine art works, I tend to use colour with intention. Every colour has a meaning and a feeling. Black for example is very strong and expansive so I tend to reserve it for deities like the figure in The Empress, 2021. Most of the figures in A Spiral Shell are drawn with black sumi ink then washed with colour, indicating that although they have human features, they are not human.

I have always felt self-conscious of using black to depict people of African descent because I feel it’s part of a visual language rooted in Black subjectivity mediated by the White gaze. My relationship with colour is very intimate. My wardrobe often shifts towards whatever my palette is at the time. I stopped wearing black a few years ago. I considered bringing it back into my wardrobe now that it’s back in my work, but I think it’s still too heavy for me. Lately, I’ve been really drawn to browns like Indian red and raw umber – they are comforting.

SC: Could you expand on the figures you depict — who or what influences their forms?

CE: Almost everyone who influences my figures is dead and has been dead for a very long time. I am often looking backwards and outside of the West. In a recent article by the Paris Review, writer Sasha Bonet describes collage as a practice of the Black imagination that helps us continue to dream in the face of violence and uncertainty. I really identify with this in terms of my approach to making figures and images. I’m drawn to all examples of human creativity. Whether it’s vintage manga, African textiles or prehistoric European sculpture I take what vibrates with me and I put it together.

SC: What are you currently reading?

CE: Currently poking around How to carry Water: Selected Poems by Lucille Clifton and The Complete Stories by Clarice Lispector.

Feature image: Chioma Ebinama, Petting a bumblebee, 2021. © Chioma Ebinama. Courtesy Maureen Paley, London