Interview: Painter Kat Lyons On Non-Human Empathy & Her Debut At Pilar Corrias

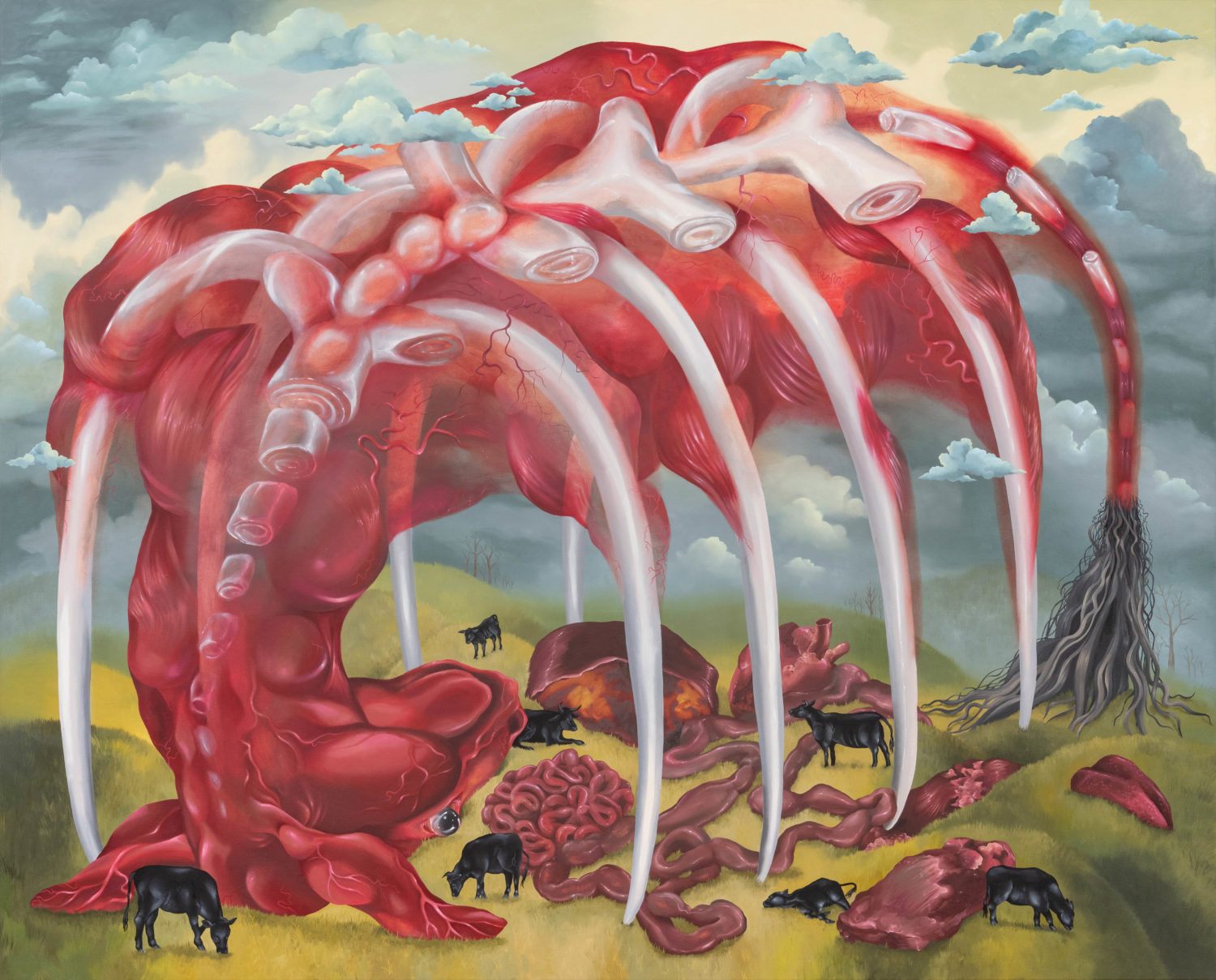

By Something CuratedOpening on 9 December 2021 and running until 15 January 2022, London gallery Pilar Corrias is set to present an exhibition of new work by American artist Kat Lyons at their Savile Row site. Titled Early Paradise, this will be the artist’s first solo exhibition in the UK, showing thirteen paintings based on Lyons’ experiences living on a small, diversified livestock farm. On the farm, facing grief offers the chance to combat the harmful systems that leave animal husbandry often irresponsibly managed. Through her work, the artist challenges the normalisation of this emotion, suggesting that it is not a defect to be remedied. In her compelling paintings, she explores what interconnectedness might mean for the inhabitants of the farm who are not directly cared for, from ant colonies to an out of commission horse. Her theatrical vignettes of animals and insects are wrought with an eeriness that is indicative of the anxiety and grief materialised amongst non-humans living in the Anthropocene. To learn more about the artist, her fascinating practice, and the upcoming show with Pilar Corrias, Something Curated spoke with Lyons.

Something Curated: Can you give us some insight into your background and how you first became interested in art-making?

Kat Lyons: The visual language is my first and the one I feel most comfortable communicating through. I have been making images for so long, but truthfully only recently began to feel responsible and happy with them. It took a while for me, as it does for many artists, to figure out the practices that best communicate what feels important. I am often overwhelmed by everything I still want to learn. When I was young, I watched my twin brother draw comics. He arranged his figures in ways I didn’t expect. I loved the feeling of surprise that came with watching him piece them together. I think I started making things because of that feeling. I completed a BFA, but rarely felt connected or excited in that environment, so going to Skowhegan in 2019 was huge for me. It was a new feeling of openness and communion, one that I think drives motivation to seek alternative forms of learning in the future.

SC: What is the thinking behind the selection of works included in your upcoming exhibition at Pilar Corrias?

KL: This series of work is very special to me. It chronicles two years spent living on a small diversified livestock farm. Much of the questions and concerns raised here are topics I had spent much of my life attempting to grasp. What is our responsibility to the non-human beings who are products of our agricultural systems? I took the responsibility of what I had learned and saw very seriously, while sitting with the understanding that these exchanges are continuously complexifying and personal. In painting the initial works for the show, I realised much of the conversations I was having seemed to be about the intersectionality of grief, labour, and category – how those factors determined the kind of lives that were to be lived by the human, wild, and domesticated beings of the farm. How does it shape their experience, the terrain, and our expectations of each other? I was able to see the effects our human-centric decisions had on the nonhuman world in intimate ways. That opportunity felt invaluable.

Kat Lyons, Portrait of Lonely, 2021. Photo: Adam Reich. Courtesy the artist and Pilar Corrias, London

SC: You work with a very particular palette — how do you think about using colour?

KL: I gravitate towards a darker palette. For me, the correlation between these colours and mystery leaves room for a lot of reflection. I often feel most excited by paintings that capture the secretive power of night. While my paintings don’t always involve darker palettes, I want them to live in that same feeling. I also try to pay attention to colours I feel repelled by – how can they help emphasise a mood I hope to convey? A discomfort that sits with beauty. Using oversaturated, bright colours to contrast the dark feels like an internal world making it’s way out, a fleeting moment of availability, or an artificiality that penetrates the natural. In the future, I hope to move away from localised palettes in lieu of stranger combinations of colours. I think this could be a fun exercise for considering alternative ways of seeing that may be more akin to the non-human realm.

SC: Could you expand on the subjects you depict, from cows and insects to fruits — what influences their forms and the contexts you place them in?

KL: I think about the importance and distinctions of visibility often – how it can be both beneficial and detrimental to it’s subjects, and how powerfully it has determined our relationship to the natural world. Typically, I have painted the subjects of my work in a hyper-frontal manner, making them clearly laid out for visual consumption by their viewers, much like how zoos or the pet industry operate – where some of our earliest relationships with animals are formed. Recently, I have grown more curious about their individual experiences – the noumenal phenomenon beyond human capability or understanding. Those questions excite the work and I think they can provide a place to reassess our personal relationships. I typically start a painting with little planning. Everything is worked out on the canvas, which is important because the process reveals the interpretations I hold of that particular subject. By exploring form without reference or aid, I am able to understand the ways I see and have been conditioned to relate to them.

SC: What are you currently reading?

KL: Anne Carson’s Eros the Bittersweet and The Invisible Painting, a memoir of Leonora Carrgington written by her son.

Feature image: Kat Lyons, Orchard (Monoculture), 2021. Photo: Adam Reich. Courtesy the artist and Pilar Corrias, London