Interview: Mahmoud Khaled On House Museums, Insomnia & His New Show At The Mosaic Rooms

By Something CuratedBorn in Alexandria, Egypt, and currently based in Berlin, Germany, visual artist Mahmoud Khaled’s process-oriented and multidisciplinary practice could be regarded as formal and philosophical ruminations on art as political activism — a space for critical reflection. Moving between the scale of the minute and a more immersive totality, his work takes on failure, austere violence and the aesthetics of an institutional heritage. From 22 June – 25 September 2022, London’s The Mosaic Rooms will present Fantasies on a Found Phone, Dedicated to the Man Who Lost it, the first UK solo exhibition by Khaled. Through a series of unfolding installations and interventions the artist builds an immersive environment, ambitiously transforming The Mosaic Rooms’ period, domestic architecture into the imagined dwellings of the owner of a lost phone. The work continues Khaled’s interest in historic house museums and the nostalgia and memorialising of individual perspectives found in them. In this new commission the artist repositions this museological form in a contemporary queer lens to explore male identity and intimacy. To learn more about Khaled’s practice and the upcoming exhibition, Something Curated spoke with the artist.

Something Curated: Can you give us some insight into your background and journey to art-making?

Mahmoud Khaled: Well, I was trained as a painter in a classical fine art school in Alexandria, Egypt (where I was born and raised) from 1999 to 2004; it took me some time after that to come over this particular academic education of art, and find what I want to say and how to say it in my work. I experimented a bit with some minimal and conceptual works as a reaction to the very formal and classical education I had. Six years later I joined an independent study programme in Beirut, at Ashkal Alwan, which was very important for me on many levels. Then I spent three years in Norway to get my masters degree from the Norwegian University of Science and Technology in 2017, which was also a very special period for me. And of course, between these educational programmes, there was a lot of learning happening through a lot of ups and downs in the world around me, influencing how I think of my position as an artist.

SC: What is the thinking behind your upcoming exhibition at The Mosaic Rooms?

MK: The exhibition is an attempt in making a portrait of a man based on the content of a mobile phone he lost in a public toilet, trying to understand how a device can reflect a persona and speak on behalf of it.

SC: Could you expand on the significance of the show’s title, Fantasies on a Found Phone, Dedicated to the Man Who Lost it?

MK: The title is inspired by a beautiful work by the German artist, Max Klinger, Fantasies on a Found Glove, Dedicated to the Lady Who Lost it, which consists of ten etching works that document and celebrate Klinger’s emotional and sexual obsession with an unknown lady based on a glove she lost in a skating rink in Berlin in 1878. The drawings are so fantastical and left a strong impact on me as they sensitively described the artist’s pain and struggle with love, longing, loneliness, and paranoia, all generated by a long and intense state of insomnia, which metaphorically describes the situation of many individuals in our contemporary time. I remember after experiencing this piece for the first time, I kept wondering about what Mr. Klinger would do if he was living in our world now and found a mobile phone instead of an elegant feminine glove? And this question is what kept me going and working on The Mosaic Rooms show during the last year.

SC: How do you approach memorialising an individual through an environment?

MK: For me, the existing format of house museums is a good answer to this question. It’s a form of a museum that I love and enjoy visiting whenever I am in a new city. The moment when a normal house gets transformed into an exhibition is very interesting for me, as it opens a lot of questions about the power and politics behind this transformation of the domestic space. Who deserves to be memorialised more than others? What do we include and exclude from the mémoire of the individuals while we are memorialising them? How can domesticity (as a device) represent the legacy of the person who used to own it? Also, there is a strong connection between this form of museum/memorial and absence, which makes it even more interesting to me, since house museums can only exist once the person disappears from our life by literally disappearing, dying, or being exiled.

SC: What interests you in the idea of sleeplessness and how does this manifest in your work?

MK: I think humans are mostly uncomfortable with any state of precariousness, although a lot can happen in precarious situations. Insomnia is one of those precarious situations that we try so hard to change and control, but after a while, we decide to normalise it and embrace it as part of our characters and way of living, and we even describe it like this in our social encounters with others, no matter how much we suffer from it. For me, it is pretty similar to exile. When you are up at night and can’t go back to sleep, you are almost exiled, as if you are forced to leave a certain geography, and you are not allowed to go back to it. Although you probably want to or are trying hard to go back, you can’t, and what happens in exile is always quite special, like what happens when we are in a sleepless state.

Even if nothing much happens and you are only thinking with your eyes open staring at the ceiling of your bedroom, what happens in your mind and feelings at this time will mostly control and shape your next day and affect your professional, social and love life – that’s why it is so interesting for me. Most of the ideas and meanings I am concerned with in my work can be related to the effect or consequences of insomnia, such as variability, loneliness, anxiety, sexual frustration, displacement and exile, and the fluidity of time and place. We all experience these things once we have been through a period of sleeping disorder, and we usually rush to grab our mobile phone with all the apps and pictures it contains as a salvation space from all this.

SC: What are some of your favourite cultural spaces in Berlin?

MK: I love spending time at HKW – House of World Cultures – seeing their shows and programme is always a great learning experience for me, as most of their curatorial projects are very well researched, which makes the experience so rich. Also, I appreciate the attention they pay to exhibition design and architecture, which positively surprises me every time I see an exhibition there. Silent Green is another favourite space for me in Berlin; their shows always require a lot of time and attention to watch and grasp, which means that I will spend most of half a day there and end it with a nice light meal and a drink in the garden of their Mars bar/restaurant.

Mahmoud Khaled’s Fantasies on a Found Phone, Dedicated to the Man Who Lost it runs at The Mosaic Rooms from 22 June – 25 September 2022

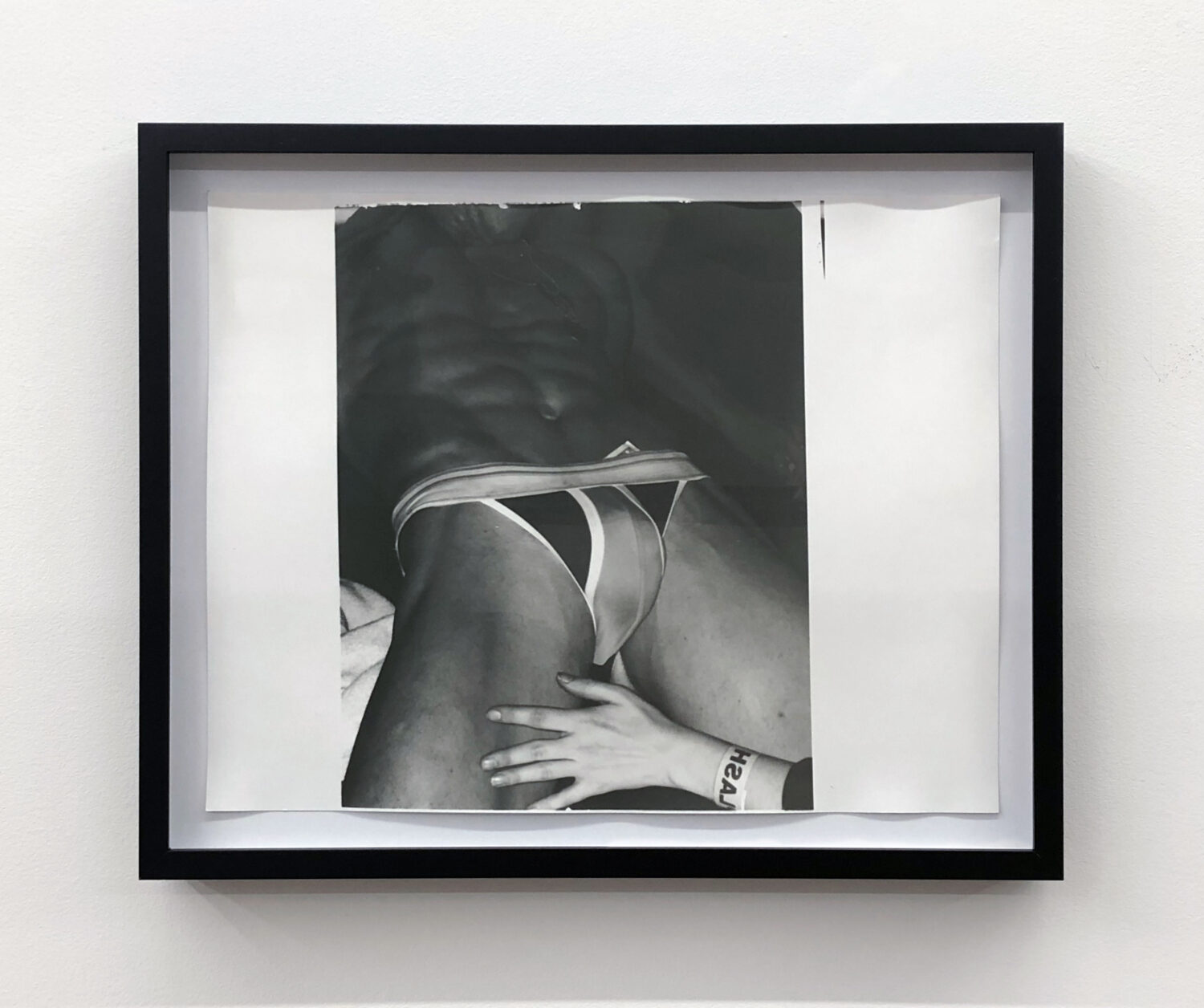

Feature image: Mahmoud Khaled, Still life (notes on justice). Courtesy of the artist and Gypsum Gallery